Most Europeans support nuclear energy. Why is Germany defying the trend?

Examining the symbolic cloud that lingers over the nation

`

"It's not the end of the world, it's just the beginning of the next”

- from German novel Die Wolke, 1987

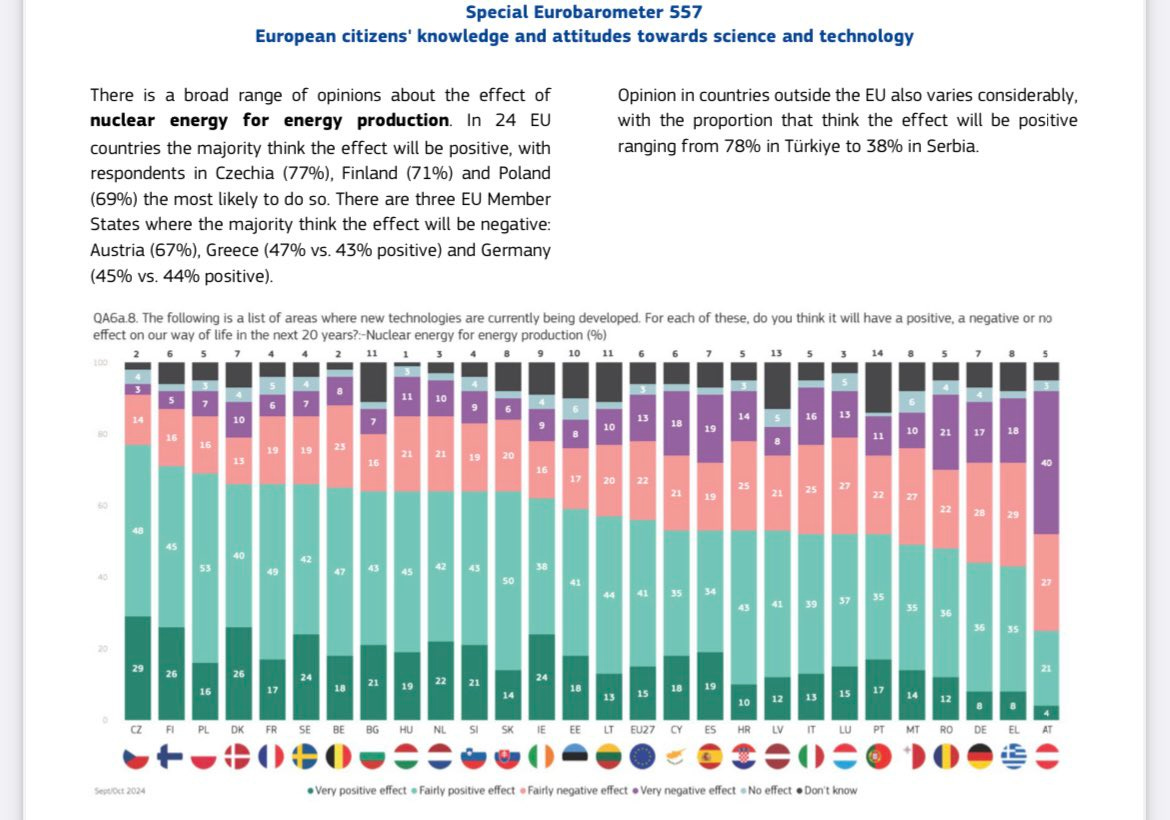

According to a recent survey, Germany and Austria are the two most anti-nuclear countries in the European Union, while Czechia, Finland and Poland are the most positive.

Earlier surveys indicated that support for nuclear energy in Germany is much higher than this, which is likely due to how the question about nuclear energy was framed. Having spent many years in the anti-nuclear movement, and more recently advocating for nuclear energy in these countries, my experience is that Germans and Austrians are among the most strongly anti-nuclear populations in the world.

Why are these countries the outliers in Europe?

Germany’s opposition to nuclear energy is rooted in a mix of historical, environmental, and political factors. The immediate backlash against nuclear energy is understandable; the 1986 Chornobyl disaster caused radioactive fallout across Europe, including Germany, sparking widespread fear and mistrust.

Due to the Soviet Union's secrecy about the scale of the problem at the time, no one knew exactly what had happened, and there was limited understanding of radiation, which was largely associated with the atomic bomb and the aftermath of Hiroshima in 1945. In an effort to protect against potentially radioactive rain, children were advised not to play outside, but they had already been doing so for days. Germans were warned not to eat rain-soaked crops, but by then, they had already been doing so for days. This went on for months, with little understanding of radiation that persists to this day in Germany. While there were no direct deaths in Germany from the Chornobyl meltdown, the fear was palpable. The situation had all the elements of the perfect apocalyptic scenario. Then, the 2011 Fukushima disaster further solidified German concerns about nuclear power, and triggered a traumatic response.

We know what happened next - a complete nuclear phase out. However, Japanese people had similar fears following Fukushima and had similarly panicked. However, Japan has now reversed its decision to phase out nuclear, and is gradually restarting its reactors. Why hasn’t Germany followed suit?

It all boils down to storytelling. In Japan, the government now confronts technological fears directly, even going so far as to have Prime Minister Fumio Kishida eat fish from the sea where treated radioactive wastewater from the Fukushima meltdown was released, broadcast live on TV. No one has taken this approach in Germany, in politics, industry, or otherwise. When I was filmed for a German documentary for ARD in 2023, the director told me he was intrigued by my straightforward, no-nonsense approach to discussing nuclear energy, especially as an environmentalist, because that kind of directness was simply unheard of back home.

To understand why fear of nuclear power runs so deep in Germany, we need to take a closer look at the country’s pop culture.

Who doesn’t love a good story?

In Germany, terrifying apocalyptic anti-nuclear storytelling is ubiquitous, and pop culture has played a major role in shaping the country's anti-nuclear sentiment since the 1970s and 80s. When comparing anti-nuclear literature and films across Europe, Germany stands out as the most prominent.

German documentaries have long questioned the safety of nuclear energy. The documentary Der Atomstaat (The Atomic State), released in 1981, criticised the relationship between the state and the nuclear industry and the perceived complicity of government officials in pushing nuclear energy without considering public safety. Another documentary released in 1986, Tschernobyl: Was passiert, wenn wir Gott spielen? (Chornobyl: What Happens When We Play God?), emphasises the moral and ethical implications of nuclear power, particularly the idea that humanity has been tampering with forces beyond its control. Under Kontrolle, which was released in 2011, is critical of nuclear energy and focuses on the challenges of managing the technology.

Then there is cinema. The film Der Dritte Weltkrieg (World War III), released in 1998, was a German-American TV mockumentary depicting an alternate history in which Soviet hard-liners rebel against Mikhail Gorbachev and accidentally trigger a nuclear war. In the 2018 film Wackersdorf, the Bavarian state government wants to build a nuclear reprocessing plant, and the confronts protesters with violence. The hero of the story discovers health risks linked to the plant and is persecuted by the state. And then there is the screen adaptation of the book Die Wolke - but we will get to that in a minute. There are more examples, but I think you get the idea.

German music isn’t to be left out. Nena’s song 99 Luftballons (99 Red Balloons), released in 1984, is perhaps the most famous anti-nuclear anthem in Germany. The lyrics tell the story of 99 balloons, which are released as a prank, being mistaken for UFOs and triggering a nuclear war. Although the song is about war, it became a powerful symbol of anti-nuclear sentiment in Germany and globally.

Then there are the stories. Numerous written works have bolstered negative perception of nuclear energy in Germany. Although written by an Austrian, Robert Jungk’s Der Atomstaat (The Atomic State), which was first published in German in 1977 and argues that nuclear energy, weapons, and radiation are immense societal risks, is considered a key text within the anti-nuclear movement.

There are others, but I’ve saved the most impactful novel for last because it requires a more detailed look. The pièce de résistance is a profoundly influential text that is still taught in schools across Germany today: Die Wolke. Translated as The Cloud and published in English as Fall-Out, Die Wolke was written by the prolific German author Gudrun Pausewang in 1987. It is a chilling novel that, in the words of a critic from Die Welt, “brought the apocalypse into children’s bedrooms.”

The story follows a Chornobyl-like nuclear disaster occurring in Germany. The protagonist, a fourteen-year-old girl named Janna-Berta, escapes the radioactive fallout and witnesses the breakdown of social order that follows. She attempts to flee with her younger brother, Uli, but there is chaos on the roads, and Uli falls off his bike and dies when he is run over by a car. After hearing about a nearby nuclear accident, Janna tries to flee with her younger brother, Uli. However, chaos ensues on the roads, and Uli falls off his bike and is tragically run over by a car. Janna is exposed to radiation, collapses, and becomes contaminated. She later wakes up in a makeshift hospital, where she is confronted with the brutal and intense suffering of others.

It makes The Last of Us seem tame.

And it gets worse. Janna hair starts to fall out as she battles the effects of radiation. While in hospital, she befriends a girl called Aisse, who succumbs to radiation poisoning. Her aunt arrives with the devastating news that her parents and younger brother have also died. When her hometown is no longer in the exclusion zone, she returns, only to find her grandparents, who have just returned from holiday, struggling to comprehend what has happened because the authorities have completely hidden it from the world. At the close of the book Janna has to reveal heart breaking truth: nuclear energy has destroyed their world.

What’s the story behind the story?

In many ways Die Wolke is not an exceptional book. It follows a classic misanthropic narrative: people commit wrongs, they are guilty of significant sins, technology is our downfall rather than our salvation, and we cannot be trusted to control it.

Read my post examining these core hippy values:

Of course, Germany’s history is also tied up with WWII, but that doesn’t fully explain why they dislike and fear nuclear energy so much. After all, many countries have a civil energy program but no nuclear weapons, and vice versa. The two do not go hand in hand, as they are different types of technology. For many Germans, however, they are one and the same thing. That is where this book comes in.

It’s difficult to imagine a more powerful and persuasive piece of propaganda than Die Wolke (and I’m hesitant to provide examples, lest I offend you, dear reader). Pausewang clearly believed nuclear energy presented an existential danger, and she covered similar themes in another children's classic, Die letzten Kinder von Schewenborn (The Last Children of Schewenborn), which was published in 1983, in which a group of children survive nuclear war, pick their way through the ruins, then die agonising deaths.

To say that her works are graphic and disturbing is an understatement. Die Wolke is a tough read, depicting societal collapse, radiation sickness, and immense suffering. When it was first released, even publishers were apprehensive about how it would be received. The teacher's guide included a warning, advising that “The teacher must consider whether it is reasonable to allow younger students to read Die Wolke alone at home.”

In a different time or country, this book might have been nothing more than a popular scary story. Instead, Die Wolke built on an already-established narrative. It captivated a nation, selling over a million copies and defining an entire era. To many West Germans who read it as children and teenagers, it is emblematic of the 1980s. Schools were named after Pausewang, and she received numerous awards for Die Wolke. Years later, in 2006, the book was adapted to the screen in the style of a disaster film.

The decision to include Die Wolke as part of the German school curriculum was made by educational authorities at the state level. A year after the Chornobyl disaster, the novel was introduced to upper-grade students in many German schools, particularly in subjects like German literature, social studies, and ethics. The book’s inclusion in the curriculum was widely supported, and when experts from the Ministry of Family Affairs raised concerns about making Die Wolke compulsory reading, they faced public outrage. Anti-nuclear hysteria had taken hold. Notably, there does not seem to be a similar book taught about fossil fuels in German schools.

As a fan of science fiction, which is often dystopian in nature, I am not blaming dystopian narratives for the lasting anti-nuclear hysteria. The combination of a masterful storyteller and real-life, terrifying events made Die Wolke more than just a story: it seized a moment in time and captured an entire generation, which has held onto that fear ever since.

Read my post on why we should consider meltdowns in context:

Gudrun Pausewang passed away in 2020 at the age of 91, but the legacy of her words endures. The fictional children who suffered in her stories continue to cast a shadow over a nation that has yet to reconcile its relationship with the power of the atom. Dystopian narratives remain a cloud that hangs over Germany. Before the country can fully embrace nuclear energy again and make a long-term commitment to it, there must be widespread public engagement initiatives to address the deep-rooted fears and perceptions surrounding the technology. If I were Friedrich Merz, I’d be preparing to eat a lot of fish.

Good commentary here, Zion. I agree with all of it. But it's not quite complete. There is another much grimmer aspect to all this.

For all of its history since 1945, Germany was on the front line of the Cold War conflict between NATO and the USSR. This meant that Germany was likely to experience the first use of nuclear weapons if the Cold War ever turned into an active war. Over the eight decades since WW2, this understandably would have traumatized the German population about nuclear technology. The difference between nuclear power and military use of nuclear technology has never been clearly explained to the general public.

Second, the Soviet Union had a strong incentive to corroding German use of nuclear power generation. The USSR produced nothing that Western economies wanted. Except oil and gas. There was a huge demand for oil and gas in Germany if the alternative (nuclear power) could be discouraged or shut down. This was a principal project of the KGB starting in the 1960s. Its success was the principal reason why Yuri Andropov was chosen to succeed Leonid Brezhnev in 1982.

Andropov's program included extensive work in supporting an assortment of antinuclear groups and political causes. So to some degree, German antinuclearism is at least in part an artifact of Soviet political interference in a NATO front line state during the Cold War. The fact that the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 in no way diminishes the strength of this effect.

Thank you, Zion, for refreshing my memory on how fears of radiation have been pushed higher and higher in Germany.

Another example, not just in Germany but worldwide, is the HBO mini-series Chernobyl that lives from pushing radiation fears high and higher.

From a historical and physics perspective, this series was very well made. However—and this however is a big one—all aspects of radiation damages were extremely exaggerated and in most cases pure nonsense.

You may be interested in Dr. Shapiro assessment. Shapiro holds both a medical degree and a PhD from Kiev, Ukraine. In 1986, when Chernobyl happened, she was one of the first medical responders sent to the most radiation-contaminated areas of Chernobyl and led the field team surveying the medical effects on children in the vicinity.

You can see her assessment about the HBO mini-series on YouTube, where she clearly states where and how complete nonsensical exaggeration were made by the producers of the mini-series.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1GEPsSVpZY