Should we be afraid of nuclear meltdowns? I used to think so

But now I know that most of the alternatives are much worse

Chornobyl. Fukushima. Three Mile Island. Whenever I post something on social media about nuclear energy, these are the responses from people who think that they’ve instantly ‘won’ the conversation against nuclear energy. But have they?

Two weeks ago, a train carrying hazardous material in Ohio in the United States derailed and caught on fire, leading crews to perform a controlled release of toxic chemicals. 2,000 residents were ordered to evacuate the immediate area. Officials are now releasing vinyl chloride, which is associated with heightened risks of cancer, into the air from five derailed rail cars that are at risk of exploding.

Accidents like this are common in the United States - around 1,700 occur annually, and 25 million Americans live in zones that are vulnerable to derailments. Nuclear meltdowns are rare by comparison, but the fear of nuclear fallout runs deep, and even images like the above can bring to mind the mushroom cloud of a nuclear explosion. We know that nuclear weapons have been the cause of many deaths and decades of subsequent health issues, and we falsely associate nuclear bomb explosions with nuclear power plant meltdowns.

Most of us don’t know what a meltdown is. I didn’t, and so I was frightened of radiation and potential meltdowns for many years. This fear was so paralysing that I protested nuclear energy as though nuclear power plants were atomic bombs.

We should be prepared for meltdowns, but not so afraid that we make bad decisions when they do happen. There is always an explanation for why a meltdown has happened, and we need to understand this to make rational decisions about nuclear energy. So let’s consider the three most significant nuclear power plant meltdown incidents in history.

What happened at Chornobyl?

The Chornobyl disaster is the most serious incident in the history of nuclear energy.

The Chornobyl nuclear power plant had four Soviet-designed RBMK-1000 nuclear reactors, a design that is universally recognised as flawed because it can cause a steam explosion. The accident occurred in 1986 during a safety test at the power plant when under-experienced operators accidentally dropped power output to near-zero and triggered a reactor shutdown, which caused a steam explosion. The reactor’s safety systems had been manually disabled to do the test they were working on.

The situation in Chornobyl was made worse by the fact that the authorities chose not to immediately evacuate the area, but waited until around 36 hours after the accident had occurred before doing so. By that time, many residents were already complaining about vomiting, headaches, and other signs of radiation sickness. They were also not immediately and adequately treated for radiation poisoning.

The RBMK is the oldest commercial reactor design still in wide operation. The flaws in the design were corrected after the Chornobyl accident, and several of these upgraded RBMK reactors have since been operating without any serious incidents for over thirty years.

The initial explosion at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant resulted in the death of two workers. Twenty-eight of the firemen and emergency clean-up workers died in the first three months after the explosion from Acute Radiation Sickness, and one died of cardiac arrest.

Although some of the radioactive isotopes released into the atmosphere still linger in the area (such as Strontium-90 and Caesium-137), they are at tolerable exposure levels for limited periods. Some residents of the exclusion zone have chosen to return to their homes, where they live in areas with higher-than-normal background radiation levels. These levels are not fatal, and exposure to low levels of radiation over a period of time is less dangerous than exposure to a large amount in one go.

How the aftermath of a meltdown is managed is important. A report found that people in the area suffered a paralysing fatalism due to myths and misperceptions about the threat of radiation, as “individuals in the affected populations were officially categorized as ‘sufferers’, and came to be known colloquially as ‘Chornobyl victims’.”

A more tragic outcome of the misconceptions surrounding the Chornobyl accident was that doctors in Europe incorrectly advised pregnant women to undergo abortions because they misunderstood radiation exposure. Robert Gale, a haematologist who treated radiation victims after the accident, estimated that more than one million abortions were undertaken in the Soviet Union and Europe as a result of bad advice from doctors following the accident.

Misinformation can be deadly. As I’ve said before, fear of nuclear energy is more often harmful than nuclear energy itself.

Thanks to hysterical media reporting and the rapid spread of misinformation around the event, most people still don’t realise that the total death toll from the Chornobyl disaster was thirty-one people.

What happened at Fukushima?

The Fukushima nuclear disaster occurred in 2011 at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan. The cause of the disaster was the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which was at the time the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan. The earthquake triggered a powerful tsunami, with thirteen-metre-high waves damaging the nuclear power plant's emergency diesel generators.

In the hasty evacuation that followed the nuclear accident, 573 stress-related deaths were recorded. The poorly-managed evacuation process caused people to panic, which led to accidents, injuries, and deaths.

The most significant reaction to the events in Fukushima was Germany’s response, as, despite not being vulnerable to tsunamis, they decided to close their entire nuclear power fleet. As a result, their coal consumption has skyrocketed, and a report found that 630 people in Germany died from coal-related illnesses in 2013 alone. Another paper concluded that this air pollution is now killing an extra 1,100 people a year. That’s vastly more than were harmed by the Fukushima nuclear power plant meltdown. And that’s before we factor in the toll due to increased global heating, which nuclear energy is one of our most powerful tools to mitigate.

Japan also shut down their nuclear power plants in the wake of the disaster (although they recently reversed this decision). A study found that if both countries had reduced fossil fuel power output instead of nuclear energy, they could have prevented 28,000 air pollution-induced deaths and 2400 MtCO2 emissions between 2011 and 2017.

Again, fear of nuclear meltdown led to more harm than the meltdown itself.

A small increase in thyroid cancer rates was initially found amongst the surrounding population, but the United Nations Scientific Committee on Effects of Atomic Radiation and the World Health Organisation concluded that this increase was due to better screening of thyroid cancer, not due to increased radiation exposure.

One person sued the government for damages for lung cancer and won, but the cause of his death has been disputed, as lung cancer is not a likely outcome of a nuclear meltdown, and other workers were not affected.

Most people don’t realise that while many people died due to the actual earthquake and tsunami, and some from the poorly handled evacuation, no one died because of the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant. The real negative consequences of the disaster came from the panicked reaction to it.

What happened at Three Mile Island?

The Three Mile Island accident was a partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania in 1979. It is the most significant accident in U.S. nuclear power plant history and was caused by a cooling malfunction that caused part of the core to melt in the TMI-2 reactor, which was destroyed.

Due to the accident, some radioactive gas was released, but there was not enough to cause any dose above background levels of radiation. More than a dozen major independent health studies of the accident found that:

“The approximately 2 million people around TMI-2 during the accident are estimated to have received an average radiation dose of only about 1 millirem above the usual background dose. To put this into context, exposure from a chest X-ray is about 6 millirem and the area’s natural radioactive background dose is about 100-125 millirem per year for the area. The accident’s maximum dose to a person at the site boundary would have been less than 100 millirem above background.”

After thousands of environmental samples of air, water, milk, vegetation, soil, and foodstuffs were analysed, researchers concluded that the release of radiation had “negligible effects on the physical health of individuals or the environment.”

Most people don’t realise that there were no injuries, deaths or direct health effects caused by the meltdown at Three Mile Island.

Wildlife in radioactive exclusion zones

The exclusion zone around Chornobyl is now home to thriving populations of animals including wolves, eagles, deer, lynx, boar, beavers, elk, and bears. Wildlife is also thriving around the Fukushima power plant.

Ecologist Jim Beasley, who studies wildlife in contaminated areas of Chornobyl and Fukushima, found that populations of animals have been increasing and thriving in both regions, despite the high contamination. “I’ve never seen an animal with an outward visual deformity from radiation,” he asserts. Even in the most contaminated areas, none of the seventeen species that Beasley and his team documented were affected by radiation levels.

The Chornobyl exclusion zone is now home to European bison and Przewalski’s horse, previously rare species that were introduced to the area after the accident to help with their conservation. Przewalski’s horse is one of the most endangered animals on Earth, previously so rare that it existed nowhere in the wild just a few decades ago. A population now thrives in Chornobyl.

Beasley comments that “this image or perception of Chornobyl [as a barren wasteland] that I had might not be a reality… Our simple presence and use of a landscape can in some cases be more detrimental to the long-term survival of a species than a nuclear accident.”

Putting disasters into context

I don’t want to make it sound like the deaths that occurred due to meltdowns don’t matter. They do, and we should do everything possible to minimise future accidents and harm to human health and the environment. But the frank truth is that no activity is risk-free, whether we’re talking about driving, eating, heating our homes, walking or something else.

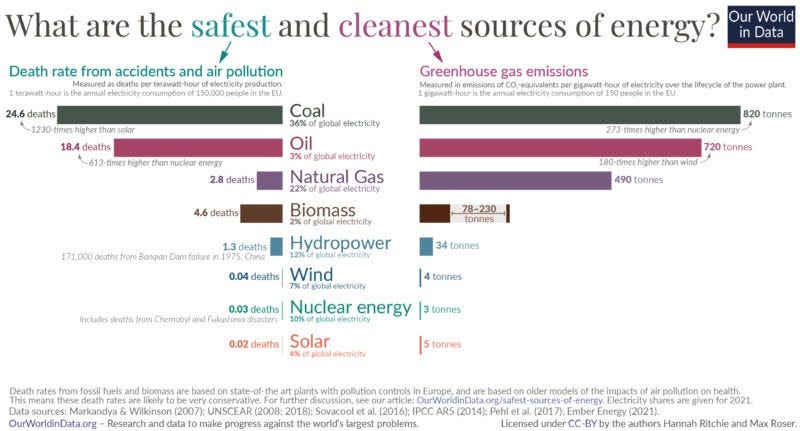

This data from Oxford University takes into account all of the nuclear meltdowns that have taken place, and it shows that fossil fuels are still significantly more harmful than nuclear energy:

Since the aforementioned meltdowns occurred, nuclear power plants have been made safer than ever before. The RBMK reactors that are still in operation have been upgraded. Authorities like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) work to monitor and ensure the safe, secure, and peaceful uses of nuclear science and technology, even basing themselves at the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant in Ukraine and holding talks with Russian officials to ensure the safety of the plant (where, despite a fire outside the site and being taken over by Russians, no one has been harmed because of the power plant). Nevertheless, there was a lot of media hype and scaremongering around Zaporizhzhya. Meanwhile, fossil fuels continue to kill hundreds of us daily. (In 2022 the Ukrainian government reaffirmed its commitment to nuclear energy.)

Stories of radiation scare us because we’ve watched them play out on screen so many times in the world of fiction, because people have spread misinformation about disasters, and because we conflate nuclear meltdowns with the fallout from atomic bombs. The outcome of this is that we are frightened of the wrong thing.

You might ask why we need nuclear energy when we can have renewables instead. Renewables can play a role in the clean energy transition, but if, as I believed, you think that they’re vastly safer than nuclear energy, take a look at the above graph again.

Hydropower is clean and more reliable than other types of renewable energy, but it can also be very dangerous. The 1975 Banqiao Dam failure was the collapse of the Banqiao Dam and 61 other dams in Henan, China, under the influence of Typhoon Nina. 26,000 people died in the floods, and an estimated 145,000 people later died from epidemics caused by contamination of the water and from famine. Estimates put the total death toll at more than 220,000 people. Over 10 million people were affected by the disaster.

Take that in for a moment. That’s more deaths from hydropower than from all of the nuclear meltdowns in history combined, including the worst three meltdowns discussed here.

Yet people do not protest hydropower and politicians do not ban it. Nor am I arguing that we should do so. We need all the clean energy we can get to meet the world’s growing energy needs while also tackling air pollution and global heating. Where hydropower is available and suitable, it should be built.

As the graph shows, fossil fuel alternatives to nuclear energy are far more dangerous.

For too long, we have listened to environmental activists who fear nuclear energy and taken in their scaremongering and clever messaging over science and reason.

Nuclear power plants are ridiculously safe. The powerful earthquake that recently hit Turkey and Syria has killed over 34,000 people. The majority of these deaths were a direct result of poorly made buildings collapsing onto people. Yet the earthquake did not damage the Turkish Akkuyu nuclear power plant there at all.

On the other hand, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill was the largest marine oil spill in history, caused by an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in 2010. A surge of natural gas blasted through a concrete core, and the petroleum that leaked from the well before it was sealed formed a slick extending over more than 57,500 square miles of the Gulf of Mexico.

200 million gallons of oil and two million gallons of chemical dispersants leaked into the sea, and the impact on the environment was devastating. An estimated one million coastal birds died as a result of the spill. The discovery of the dead corals near the spill indicates that it harmed marine life in the deep ocean. A study found heart abnormalities in fish embryos exposed to Deepwater Horizon oil. By 2013, over 650 dolphins had been found stranded in the oil spill area, a four-fold increase over the historical average. People reported symptoms including respiratory problems, blood in urine, rectal bleeding, seizures and miscarriages.

Oil spills are sadly regular occurrences. Remember also the Amoco Cadiz oil spill, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the Persian Gulf War oil spill, and many others.

Radiation, which can be easily measured, treated, and contained or shielded, is simply nowhere near as dangerous or harmful in comparison.

What about human displacement?

An argument that people make about nuclear meltdowns is that they displace people, but more people in total have been displaced by other forms of energy generation, specifically coal mining. For example, in the Lusatia region of Germany alone, 30,000 people were displaced by coal mining and more than 130 villages were deliberately destroyed, which is the same number of displacements due to Fukushima. Coal mining displaces millions.

Large dams built for hydropower, irrigation, water storage or flood control have also led to the involuntary displacement of millions of people over the last century. China's Three Gorges Dam has displaced over 1.2 million people, and in India over 16.4 million people have been displaced due to hydropower development projects. In 2000, the World Commission on Dams estimated that the number of people displaced directly by large dams between 1950 and 2000 was between 40–80 million people. This number has increased in recent years.

For the final example of the greater danger of traditional energy sources, consider the Jharia coalfield fires, which have been burning underground in India for over 100 years. The first underground fire there was ignited by unknown factors in 1916 and the fires now cover more than 100 square miles of Jharkhand State in the north-eastern province of India. Various attempts at putting them out have failed. It is estimated that 37 million tons of coal have been consumed by the fires since their start, the total emissions of which are unknown.

There has been sadly little research on the health impacts of these fires, but the toxins they release make people sick, sometimes fatally. People suffer from health issues including respiratory problems, carbon monoxide poisoning, stroke, lung cancer, pulmonary heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. As of 2007, more than 400,000 people who live in Jharia are living on land that is in danger of subsidence, i.e. sinking beneath their feet.

Coalfield fires are more common than people realise, and Jharia is just one of the thousands of fires that are burning underground around the world. For example, over 200 coal fires in Pennsylvania in the U.S. have contributed to making it one of the leading acid-rain producers in the States.

I could go on, but I think you get the picture.

What can we do?

For most of human history, we lived in poverty. A quarter of babies died in their first year of life. In 1980, around 40% of the world's population lived in extreme poverty. Today only 10% of people do.

Much of this is thanks to fossil fuels. The burning of wood, then coal, gas, and oil enabled us to prosper. This also had a significant impact on the environment and climate. For most people in the world, if you live in a building of any kind, that building was built on what was once a forest, grassland or desert. So was most of the world. To live as a human being means that we always have to make trade-offs with the environment around us. It has been this way since the dawn of humankind.

These trade-offs may sound obvious to you, but despite the positive impact that harnessing energy has had on humankind, environmental groups around the world continue to protest energy - all sources of it.

It’s easy to become downhearted by the bad news associated with energy production, but accidents must be considered in context, and our energy choices need to be informed by data, not scary stories.

Ultimately, the consequences of a lack of development are more significant than all of these accidents put together. We need energy to survive. Without it, we would be trapped in poverty. Billions of people around the world still are. Poverty is, essentially, energy poverty. To continue to thrive, warm our homes and light our streets, run hospitals and schools, and feed billions of people, we need more reliable, clean energy.

I spent over a decade trying to convince people to consume less and reduce their carbon footprints. I even wrote a book on how to do so. But the best behavioural science in the world has not found a way to make this happen. Most people choose convenience over other options: this is an easily-understandable evolutionary trait. We can and should insulate buildings, fund public transport, and take other measures to avoid energy wastage, but even if we all do this the world over, it will not mitigate our growing need for more energy.

We can and should invest in renewables, but wind and solar still need baseload power, and historically, wherever nuclear energy has been phased out, it has been replaced by coal or gas. Hydropower is more reliable, but dams are geographically restricted, and still carry significant risk.

The root problem is not growth, but the fact that we have not always balanced human needs with protecting biodiversity and the health of our planet. I have written before about how wildlife thrives around existing nuclear power plants, which has also been shown by the exclusion zones around Chornobyl and Fukushima. In contrast, the areas that are used for extracting fossil fuels are ravaged in the process and do not always recover. In light of this, to turn our backs on nuclear energy is to turn our backs on the health of the planet and all life on it.

As the old saying goes, “It is better to light a candle than curse the darkness.” All sources of energy generation cause accidents, but some are more harmful than others. Life without energy is also deadly.

We need to choose energy sources that do the least harm to the environment and human health. To do this, we need to consider our options fairly and view them in context. Clean energy is essential for replacing fossil fuels, which harm us and our planet significantly.

When we panic and react out of fear of nuclear energy, we ignore the consequences of mining and burning coal, the millions of deaths from air pollution, the oil spills and gas-related accidents, the millions of displacements, and the impact of burning fossil fuels on our climate. Through fear, we continue to make decisions in darkness. When we call for nuclear power plant closures around the world based on misplaced fear, we invite literal darkness. Meanwhile, in Jharia and other regions where coalfield fires rage, the ground is literally melting beneath people’s feet. That’s what we should really be having meltdowns over.

When Ukraine became independent, the government requested that people re-establish the original spellings of Ukrainian places. This article therefore uses their preferred spelling ‘Chornobyl’ over the Russian spelling ‘Chernobyl’. It is not a typo.

Really enjoyed this, it's great to see the reality put so plainly. Credible scientists have even argued our revised Chornobyl figures are overestimates.

I think it's courageous to be open about the risk of future accidents, especially knowing how anti-nuclear activists will warp the truth. In the spirit of candour perhaps we could state the risk numerically: e.g. 1 serious accident per X hundred years, with the loss of (<1) lives and displacement of 0 people. And use better terminology... "Nuclear meltdown" evokes ridiculous allusions to atomic weapons and the fictional China syndrome. Perhaps 'Reactor Fuel Melt' would be better, followed by an assessment of containment.

Thank you for another outstanding article on nuclear energy. I’m so glad you highlighted the negative health consequences of fossil fuels. Not enough people understand this.