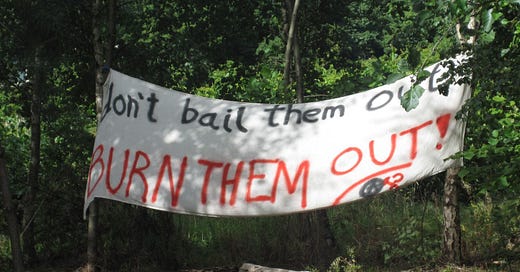

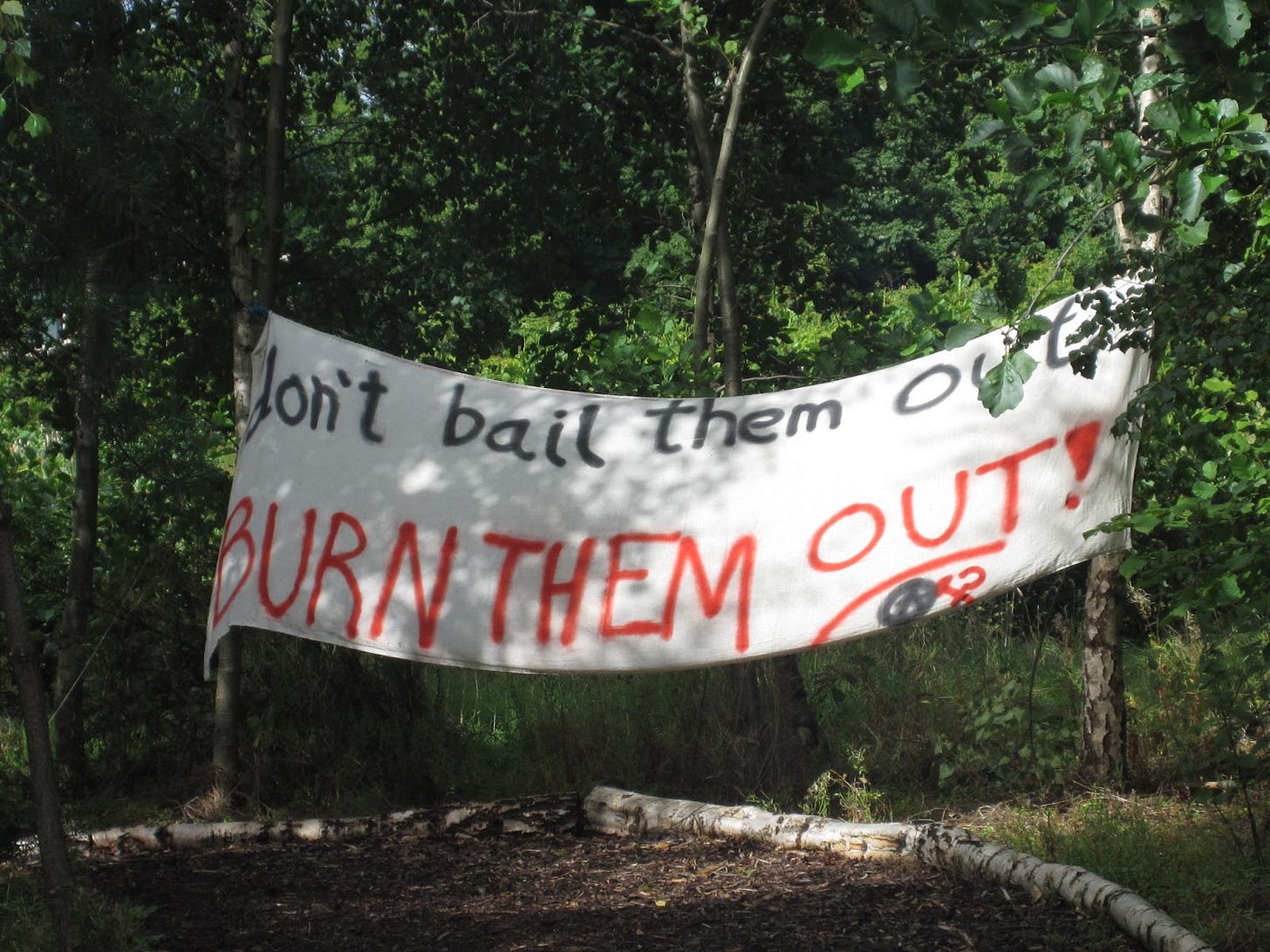

I took this photo of a banner at a hippy camp I was involved with in the early 2000s.

Humans are drawn to tribes. Whether sports fans, political groups, religious organisations, or something else, we gather in clusters where we share common ground.

I signed up with Greenpeace as a teenager when I saw one of their adverts on TV about saving the planet. Their messaging spoke to me, and most of the misinformation I received on many issues, including nuclear energy, GMOs, and so-called ‘overpopulation’, came from Greenpeace initially. They encouraged me to join similar groups, like Friends of the Earth, and attend activist gatherings like People and Planet and Earth First!, which led me further into an echo chamber of people who all believed the same things.

This broad hippy movement holds four golden beliefs:

The world is going to end because of environmental damage caused by humans (the current iteration of this is climate change)

Humans are a virus on the planet. There are too many people and overpopulation will lead to mass starvation and death

Everyone should live “on the land” without technology. Technology and modern civilisation are bad

Capitalism, consumerism and the use of money are the root of all evil and unhappiness

Ultimately, we had an anti-human perspective, with addled ideas of ‘nature’ and ‘technology’. The insidious influence of these beliefs on wider society should not be underestimated. These four tenets have come to underpin much modern thinking today.

I believed these ideas the way someone who is brought up with religion, but not religiously, might have vaguely formed ideas about God, the afterlife and so on. I did not consider them deeply, and was not meant to. We were not a religion, but in recent years I have realised that we shared many things in common with a cult.

I did all the things a good activist hippy is meant to do. I was arrested for storming a coal-fired power station, I helped to shut down a bank that was investing in tar sands, and I staked out in a tree for a week to stop bulldozers from clearing woodland. I lived off-grid in Dartmoor, just because (eff you, The Man), I backpacked and hitchhiked around Europe. We went to festivals, but only the off-grid ones that were (supposedly) run on solar power. We sweated naked in wood-fired saunas together, and we sang Imagine and Bob Dylan songs around campfires. We believed in peace, man.

My friends had psychedelic art and “Make Love Not War” painted on their living room walls. There was a lot of guitar playing, talk about how to heal the world, and (of course) tie-dye. On the surface, it was a vibrant and colourful community that believed in free expression, love and positivity. I fell for the bright rainbow colours of their brand.

‘Hippy’ has come to mean many things, and most people think of it as a harmless, ‘peace and love’ movement, or simply a way of dressing. In reality, my experience of hippies is one of angry doomers, and the flowery visage is a marketing ploy perpetuated by some of the most intolerant and controlling people I have ever known.

That’s the clincher. The beliefs held by my fellow hippies were at odds with their image. Today, we can see it more obviously - activists who preach peace but are the most rage-filled and violent of us all. They exist in every movement that is fighting for something good, yet they seldom represent what is good.

For many years, I embraced the self-flagellation, sacrifice and denial that came with this movement. I was praised for it, and I even wrote a book instructing others on how to achieve the same.

Eventually, I began to question whether we were achieving anything other than encouraging hubris and self-righteousness within our insular community.

One day I was listening to a hippy band that regularly performed at our festivals and protests, and it hit me that the angry lyrics did not represent a movement for peace and love. I realised that this was a movement of judgement and intolerance, which looked down on anyone who didn’t believe in the four golden tenets.

And so did I. And maybe I was wrong to do so.

Many years later, I worked with two prominent former hippies who had left their communities behind publicly, and who had been badly bullied as a result of this. One of them had to move house after the aforementioned band camped out outside his family’s home singing songs about his being a traitor, and the other described the “trauma” of “the scars on his back” he’d suffered from the hippy community after he’d left. They had endured these attacks with much fortitude, but the angry hippies had left marks. People aren’t meant to leave or talk about leaving the cult.

There was no single moment that led me to walk away from the hippy movement. I was attacked for including a chapter on vaccinations in my book, but I weathered it. Everything I was told about living on the land being preferable to modern life was strongly rebutted by my experience of visiting my parents’ villages in India where they had grown up in poverty, but I couldn’t debate any of this yet. Amongst the hippies, who on the surface celebrated freedom of expression, I was not able to find the words. The four golden tenets are immutable. The hippy canon was superficial and risible, and one day when I was being lectured by a friend about how I should be using tea leaves instead of tea bags, I had a strong presage that this would soon become unbearable.

It is hard to leave a community that has helped to shape you, even if the shape ultimately didn’t fit the mould they had prepared. I left because although they had become my second family, I needed to be able to develop and vocalise my thoughts, and I could not do this within their restricted tenets. The moment I realised this, I acted with celerity and publicly walked away.

Many of us do hold ‘hippy’ ideals at heart: we want to live in a time of peace, we desire a healthy planet, and we wish for life on Earth to thrive. Many of us have also, unfortunately, absorbed the four tenets of hippy ideology, including doomerism, misanthropy, overpopulation panic, and the idea that technology is bad. The ’60s may feel like a long time ago, but the movement is still active and effective today, and the same ideology still looms large.

As these old beliefs are now increasingly challenged and cast aside in favour of a more pro-human, pro-progress movement for change, I’d like to imagine instead a community of tolerant individuals, who are not so fragile that they cannot change their minds when proven wrong. A group that allows freedom of thought as much as of expression. An organisation that truly cares about people and science. It’s the only way that reason will overcome the loud and colourful ideology of the hippy movement, which is still highly influential in terms of the way we think and the decisions we make. As the rise in climate activist groups globally demonstrates, people need communities.

I think I’ve found one such entity in the Humanists, but I hope many more come to exist. That’s the new hope, man.

You may say that I’m a dreamer, but - thankfully - I’m not the only one.

Excellent article :)

When I hear Greenpeace I always think of this;

Before I was born my Dad worked on the construction of a nuclear power plant that was never completed. This was at least partly because of the intense protest by Greenpeace at the site and all around the country at the time.

Instead of a clean contained nuclear power plant, we were left with the coal fired power plant that peppered everything within 30 miles with yellow and white ash and spewed heavy radioactive metals into the air.

They've buried 60 years worth of the fly ash on the banks of the Ohio river, making the land completely toxic and unusable for the forseable future, not to mention the water. It's a few hundred feet from a State park.

I've never forgiven Greenpeace for that, they came here, spewed their nonsense and then left. They should have had to spend their childhood breathing yellow ash and heavy metals...

Difficult to read, I was there, but then asked for the science and the data.