Japan probably isn’t the case study you think it is

But we can learn a lot by navigating the stereotypes

I've noticed that people often use Japan as an example to make various arguments, including against nuclear energy and for claims that Europe is "falling" (it’s not). It’s not uncommon for someone to respond to my statements about nuclear energy with just one word - “Fukushima” - as if this alone decisively refutes the broader case for the technology.

I know people who are passionate about Japan, who have learned the language and moved there because they expected it to improve their quality of life for one reason or another. Then, after living there for a few months, they admit to finding it challenging due to the comparatively high-stress work environment and longer average working and overtime hours. Several of them have returned home, or are planning to return home.

I also encounter anime fans - sometimes referred to derogatorily as "weeaboos" - who have an obsession with a superficial, idealised, and inaccurate view of Japan. Most people's perceptions of the country fall somewhere between these two extremes.

Japan indeed provides a valuable case study for the worst-case scenario of what can go wrong with nuclear energy following the Fukushima Daiichi power plant meltdown in 2011, but not in the way people think. Although the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami had a devastating impact on Japan, killing almost 20,000 people, no one died due to the nuclear meltdown, which shows that even in the rare instance of being hit by a powerful natural disaster, nuclear power plants are still incredibly resilient, as well as safer than hydropower and wind power.

Also, the meltdown was avoidable. Research undertaken after the disaster found that it could have been avoided altogether if mitigation measures had been taken beforehand - mainly addressing outdated tsunami countermeasures. The Daiichi plant was designed in the 1960s when we knew a lot less about tsunamis and the impact they could have on energy infrastructure. However, well before the 2011 disaster, new scientific knowledge found that the Daiichi power plant was at risk of a major tsunami. Still, no one thought to implement countermeasures. Simple changes like moving the backup generators to a higher location and sealing the lower parts of the buildings would have likely prevented the meltdown or reduced its impact.

Read my post on nuclear accidents:

A few years ago, I coined the phrase: The fear of nuclear energy is more harmful than nuclear energy itself. The panicked reaction to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant meltdown supports this statement, as during the evacuation, hundreds of accidents and injuries occurred as people tried to flee the area in haste. Also, the Japanese government’s reaction to the meltdown was later found to be disproportionate, as parts of the Fukushima exclusion zone are less radioactive than parts of Cornwall, a popular holiday destination a few hours south of my home in the UK.

Worse, following the accident, Japan suspended operations at all its remaining nuclear power plants, shutting down 54 reactors and reducing nuclear energy generation from around 30% to only 1%. The country instead relied almost exclusively on imported natural gas to replace the lost electricity generation from nuclear.

There is evidence that the overreaction locally and globally has had far worse consequences than the event itself. Japan’s nuclear phase out also resulted in energy instability and increased deaths from air pollution. Since other countries, including Italy and Germany, followed in Japan’s footsteps, we do not know the full toll of all of the phase outs, but researchers crunched the numbers for Germany’s nuclear phase out - before it had even been completed - and found that it resulted in the deaths of 1,100 people a year from air pollution alone.

The complexities of ‘public’ opinion

Much of the initial backlash to nuclear following Daiichi came from a fear response and misunderstanding of what had happened. Although public perception of nuclear energy has changed in Japan, it’s not as straightforward as people tend to assume or report.

A thorough study examining public opinion published earlier this year yielded complex results. Questioning 2,600 respondents in Japan, as well as people in the US and UK, researchers found that although negative opinions of nuclear energy have decreased over time in Japan, they remain much higher now than before the accident. There were some similarities: the term “new construction” in all three countries made the respondents anxious about plant safety. But the researchers also noted that Japanese public exhibited some unusual responses compared with British and American citizens. For example, in Japan, using the phrase “nuclear power plants that no longer require evacuation” resolved the respondent’s anxiety, and researchers observed an increase in the number of respondents who agreed with the new construction of nuclear power plants.

This is perhaps understandable given that the Fukushima evacuation caused more harm than the meltdown itself, but it also shows that people’s feelings about technology can be complex and vary culturally. As we say in science communication, there is no single ‘public’, only publics - plural. Messaging that is popular in one country doesn’t necessarily directly translate to another. Responses also often vary among populations by demographics, including age, gender, social class, and so on.

The nuclear reversal

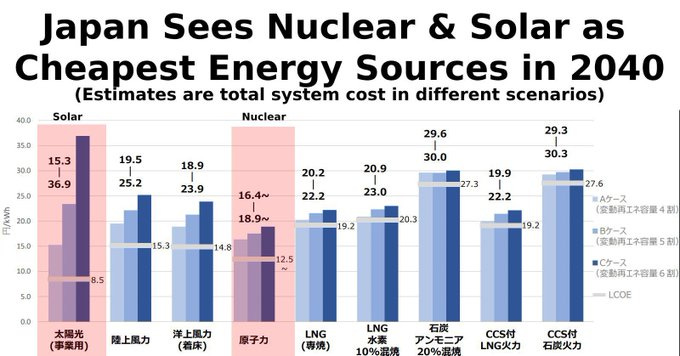

There are obvious reasons why Japan has reversed its stance on nuclear energy generation. Once the initial panic had subsided, issues related to energy scarcity became increasingly apparent. The other reason is simple economics: Japan recently released figures showing nuclear and solar as the cheapest energy sources in 2040.

In 2015, the country permitted its two nuclear reactors to resume operation. In 2024, Japan released a new energy policy announcing a target for nuclear energy to compose 20% of the country’s energy mix by 2040. To achieve the 20% target, all 33 workable reactors in Japan have to be back online, which will be a slow process. Meanwhile, safety improvements learned from the Fukushima Daiichi accident, like reinforcing tsunami walls and adding earthquake reinforcements, have also been implemented for the existing fleet of power plants.

Nuclear reactor restarts in Japan have already been found to reduce the need for liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports for electricity generation, which should provide further incentive to restart old reactors and build more.

Finally, a less-discussed reason for Japan’s shift in nuclear energy policy is the country’s declining population.

Does an ageing population need less energy?

An argument often presented by proponents of degrowth is that Japan's declining population will lead to reduced energy needs. There is some truth to this, but overall the assertion is incorrect.

This post offers a detailed analysis of why population decline doesn’t necessarily lead to less consumption:

Japan’s birth rate has been declining since the 1970s, and the country has the second-oldest population in the world, where more than one in 10 people are 80 years old or older. Despite various government incentives aimed at encouraging higher birth rates, there is currently no indication that the trend of population decline is slowing down.

The detail people tend to miss is that Japan requires vast amounts of energy to support its large elderly population. To manage this, the country is becoming increasingly reliant on technology, particularly power-hungry robots and data centres running Artificial Intelligence (AI), which means that energy consumption is likely to increase or stabilise rather than decrease due to fewer births, but is estimated to increase by 50%.

Finally, we have found a stereotype with some truth to it - Japan is also one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world, widely recognised for its technological advancement, expertise, and literacy. As other countries will soon follow the same trajectory of population decline as Japan, their energy needs are also likely to increase.

Another thing people like to argue is that Japan is a case study for excelling while rejecting immigration and diversity. In fact, the opposite is true.

Due to workforce shortages caused by its shrinking population, Japan has implemented several measures to promote immigration, including increasing the number of young immigrants allowed into the country, allowing low-skilled workers to live and work in Japan for five years, and permitting foreign workers with specialised skills to emigrate indefinitely with their family members.

Japan is not as ethnically homogenous as many people believe but is, in truth, moderately diverse. 1 in 10 residents of Tokyo in their 20s are foreign-born. This trend is not restricted to urban areas - migration also occurs in small industrial towns around the country. In some towns, migrant populations constitute over 15% of the local population, and in the mostly rural Mie prefecture, foreign migration has balanced many years of population loss.

Unlike the backlash that much of the Western world has been experiencing over immigration, most Japanese people appear to support it. In a survey published in 2024, 62% of Japanese respondents favoured granting more visas to skilled foreign workers. There is a broad understanding that the country needs more people, especially workers in key industries such as healthcare and construction.

So, as much as I enjoy watching the occasional anime, which, perhaps ironically, almost always features young characters as protagonists, it’s fair to say that Japan looks very different in real life. It will be challenging for the country to continue to adapt to its changing population and meet its energy needs when there is an ongoing workforce shortage.

Returning to the nuclear age will undoubtedly help - Japan has learned the hard way that nuclear energy is irreplaceable. Moreover, it will play a crucial role in how well a country experiencing population decline can maintain living standards. If Japan cannot address the deficit of qualified professionals, the construction and operation of nuclear power plants may need to be increasingly automated and handled by AI. Not to stereotype, but given their technological prowess, it seems plausible that if any country is likely to develop and implement such advancements, it will be Japan.

"The fear of nuclear energy is more harmful than nuclear energy itself. "

This has always been true. In 1979, the accident at Three Mile Island killed or injured no one from radiation exposure. However. there was a voluntary evacuation (read 'panicked flight') from the area within 5 miles of the site because of an erroneous public warning by Pennsylvania State Governor Richard Thornburgh. In total, 140,000 people fled the area. This would have caused injuries or fatalities from traffic accidents.

But the long term consquences were much more severe. At that time over 200 additional power reactors had been planned for the United States in various locations. As a result of TMI, all of them were terminated. Nearly all of those under construction at the time were also terminated. Instead, coal-fired plants were retained in operation. This will have produced injuries and loss of life expectancy because of the retained coal-fired capacity. This would have come primarily from toxic heavy metal emissions from burning coal.

Excellent post as always. I thought you could have said more about the complete reversal of direction and policy in Japan regarding nuclear power. “If the place that originated your one word condemnation of nuclear power has re-embraced it how is this an argument against; it is an argument in support of nuclear”