“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

When it comes to energy, especially in conversations about climate change and renewables, there’s no shortage of hot takes and misconceptions.

Energy is complicated, and in the middle of a global push for decarbonisation, getting the basics right matters. So here are ten mistakes people make when they talk about energy.

1. Equating “renewables” with just wind and solar power

Ask most people what renewables are, and they'll say wind and solar power: the poster children of renewable energy. But even with significant finances being poured into them, the largest source of renewable electricity in the world isn’t either of them. It’s hydropower.

Massive hydroelectric dams across China, Brazil, Canada and elsewhere generate more clean power than all the world’s solar panels put together. While hydro is geographically restricted, it’s still worth remembering that it’s the most reliable clean form of renewable energy, and quite different to wind and solar, even though they get lumped together as if they are equals.

And then there’s biomass - the messy cousin no one likes to talk about, which still makes up a good chunk of the “renewable” pie in Europe.

2. Ignoring biomass and pretending it’s clean

The UK likes to claim a high share of renewable electricity, but a huge chunk of that is from burning wood pellets at power stations like Drax.

Technically, biomass is classed as renewable because the trees might grow back. But in reality, it involves chopping down forests, shipping the pellets across the Atlantic, and burning them, which releases carbon in the process.

If biomass wasn’t classed as “renewable,” the statistics for investment in clean energy would look very different for many countries. That classification is one of the biggest scams of the 21st century.

My post on why renewables aren’t what you think they are:

3. Confusing installed capacity with actual generation

This one’s everywhere. Journalists hear a country has installed 100 GW of solar and report that it now generates 100 GW of electricity. But that isn’t how it works.

Capacity is what a system could theoretically produce under perfect conditions. Generation is what it actually produces. A solar panel in Scotland in December isn't as efficient as one in Arizona in July. Since wind and solar are intermittent, i.e. they rely on weather, they rarely reach full capacity, at least not for long periods of time.

No matter how much capacity a country installs, that doesn’t increase the amount of sunshine or wind it gets. Essentially this means gambling on the weather to produce electricity. It’s never reported like that though.

4. Believing that political revolution will bring down emissions

There’s a popular belief that we can’t solve climate change without first bringing down capitalism or completely overhauling the political system. But emissions don’t wait for utopia. Most global emissions come from energy systems, supply chains, and infrastructure, which are all things that can be decarbonised through policy, investment, and technology within the existing system.

In fact, countries with strong institutions and market mechanisms like carbon pricing, clean energy subsidies, or green finance, have done more to cut emissions than revolutionary slogans ever have. Big systemic change sounds exciting, but it’s often slow, messy, and unlikely to deliver the fast, pragmatic energy transition we need.

My post on how development brings down emissions:

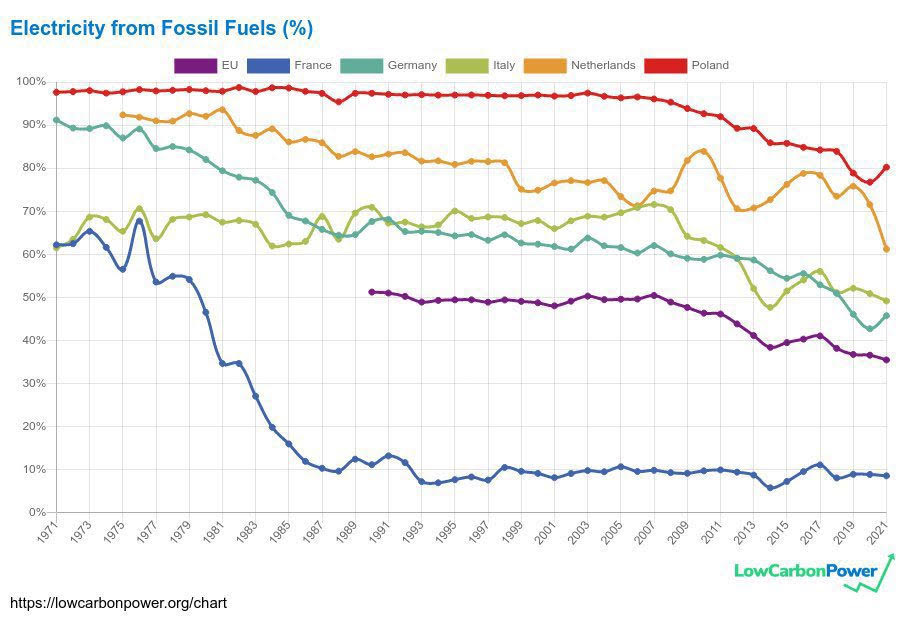

5. Ignoring Germany as a cautionary tale

Germany is - bizarrely - still often praised for leading the energy transition, simply because the German government invested massively in renewables, and despite the fact that they also increased emissions with the decision to shut down nuclear energy, kept coal running longer than anticipated, and now import power from neighbours with cleaner grids.

The price of Energiewende continues to rise, with it now predicted to cost €1 trillion. Did it reduce emissions? Somewhat. Did it do so efficiently? Not at all. Other countries, like France or Sweden, decarbonised faster and for much less money (largely thanks to nuclear). But for some reason, many countries are still attempting to follow in Germany’s footsteps, including Spain and Australia.

6. Sidelining nuclear, even though it works

Nuclear energy is weirdly political. Ideology aside, nuclear is a proven, zero-carbon source of baseload power, and it has helped countries like France and Sweden maintain low-carbon grids for decades. If we’re serious about cutting emissions, it has to be a significant part of any net zero plan.

7. Forgetting that the grid isn’t magic

Here’s one that often gets missed: the grid isn’t ready for what’s coming.

You can’t just plug in millions of EVs, install heat pumps everywhere, and stick solar panels on every roof without upgrading the grid as well. Storage, infrastructure and distribution have to scale up. Otherwise, you end up with power you can’t use or blackouts when the sun goes down and the wind dies.

Infrastructure planning is the unsexy part of energy, but it’s what makes the sexy bits work. Factoring it into solar and wind installation also dramatically increases the cost and build time for those projects, which gives a more accurate depiction of both.

8. Treating “net zero” as synonymous with “renewables”

People hear “net zero” and instantly picture wind turbines and solar panels. But net zero shouldn’t be a synonym for “100% renewables.” The goal should be clean energy and deployment that has been proven to work.

That can involve renewables, but also nuclear, carbon capture, negative emissions technologies, and in some cases, continued use of fossil fuels with offsets or sequestration. Pretending net zero is just about building more wind and solar farms misses the scale and complexity of the energy transition.

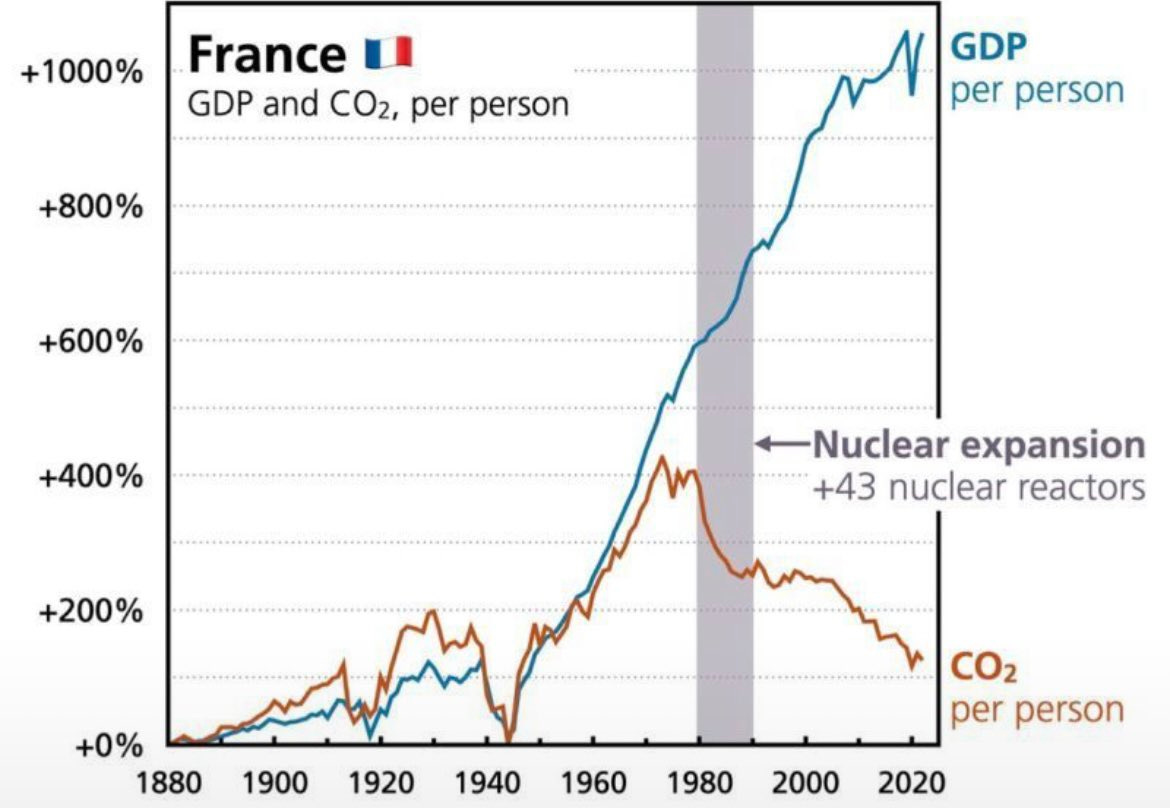

9. Ignoring the economy

France’s bold investment in nuclear energy during the 1970s and 80s didn’t just reduce carbon emissions - it also delivered a serious economic boost. By securing a stable, domestically generated supply of electricity, France reduced its reliance on volatile fossil fuel imports, insulated itself from energy price shocks, and maintained some of the lowest electricity costs in Europe for decades. This energy security supported industrial growth and competitiveness, helping to underpin consistent GDP growth through the late 20th century.

Unlike countries juggling soaring energy bills today, France reaped the economic dividends of long-term planning, enjoying some of the lowest energy prices in Europe for decades. This is important because of the mistake politicians make in…

10. Assuming net zero is the only goal

Most people say they want net zero, and in principle, they do. But when push comes to shove, what people want first is cheap, reliable electricity. That’s the baseline. If the lights start flickering or bills go through the roof, political support for climate policy evaporates overnight. We’ve seen this play out time and again: energy prices spike, and suddenly governments are backtracking on green policies or subsidising fossil fuels to keep the public calm.

It’s not that people don’t care about the planet, but the energy transition is about maintaining balance. Aside from a few extremists, most people don’t want to be cold in the winter or pay triple for their energy, no matter how much they care about polar bears. Net zero plans have to prioritise affordability and reliability, or they’ll collapse under their own good intentions. Climate action that ignores public tolerance is climate action that doesn’t last.

The takeaway

We’re in the middle of the most ambitious energy transition in history, but most people, including many politicians, still don’t fully understand how energy systems work.

Decarbonisation is an ambitious goal, and achieving it requires more than just good intentions. We just need realism, nuance, and fewer vibes-based policy decisions. We need to understand and accept the basics, which means knowing what generates power effectively, how, and where. It means accepting trade-offs. And it means acknowledging that you don’t have to personally like a form of energy generation to accept that it works and that we need to invest in it if we want to succeed.

There just wouldn't be all this nonsense if there had been good energy decisions years ago. As in more nuclear. Now hysteria has taken over and the transfer of wealth is of more importance than actual energy. There is no transition as yet - only an addition in my opinion of an inferior energy source of wind, solar and batteries. We have gained nothing, but lost billions of dollars to accomplish what?

Love the post - very much straight talk.

Excellent comments. Its amazing that a lot of even supposed 'energy experts' make the basic mistakes you outline.