What climate activists won’t tell you about protecting the planet

Mostly because they don't know

“When presented with new evidence, we must always be ready to question our previous assumptions and reevaluate and admit if we were wrong”

- Hans Rosling

When I give talks I am frequently asked a variation of the following question: how do we stop consumption and development to protect the planet?

My answer always draws blank faces. Stopping growth is not the solution to addressing climate change, I tell concerned environmentalists and anxious climate activists. We do need to decarbonise and move to cleaner technologies, but fighting development won’t save the planet, and nor has it been shown to reduce emissions.

Sometimes these remarks are met with anger. I can understand this response, since I once also believed that preventing economic growth was the solution to tackling climate change. We have been told repeatedly, by mostly well-meaning activists, that our lifestyles are the problem. This is a logical fallacy. We have also been told that to stop climate change we have to change everything immediately: stop oil, go plastic-free, stop driving, and so on, and these myths have taken hold. I, myself, wrote a book on how to live with a low carbon footprint to save the planet. While these are still admirable aims and we should all try to live less wasteful lifestyles, the hyperfocus on individual action has been at best a distraction and at worst a complete fraud.

We have also repeatedly been told that we are the problem, and therefore the solution is for there to be fewer of us. But all of this is wrong.

It may seem unbelievable that continuing on our current trajectory will solve anything, but the evidence shows that environmental progress is being made in many areas and that growth is the only thing that is working in terms of lowering emissions and improving air quality.

If we want to save the planet, we need to understand what works.

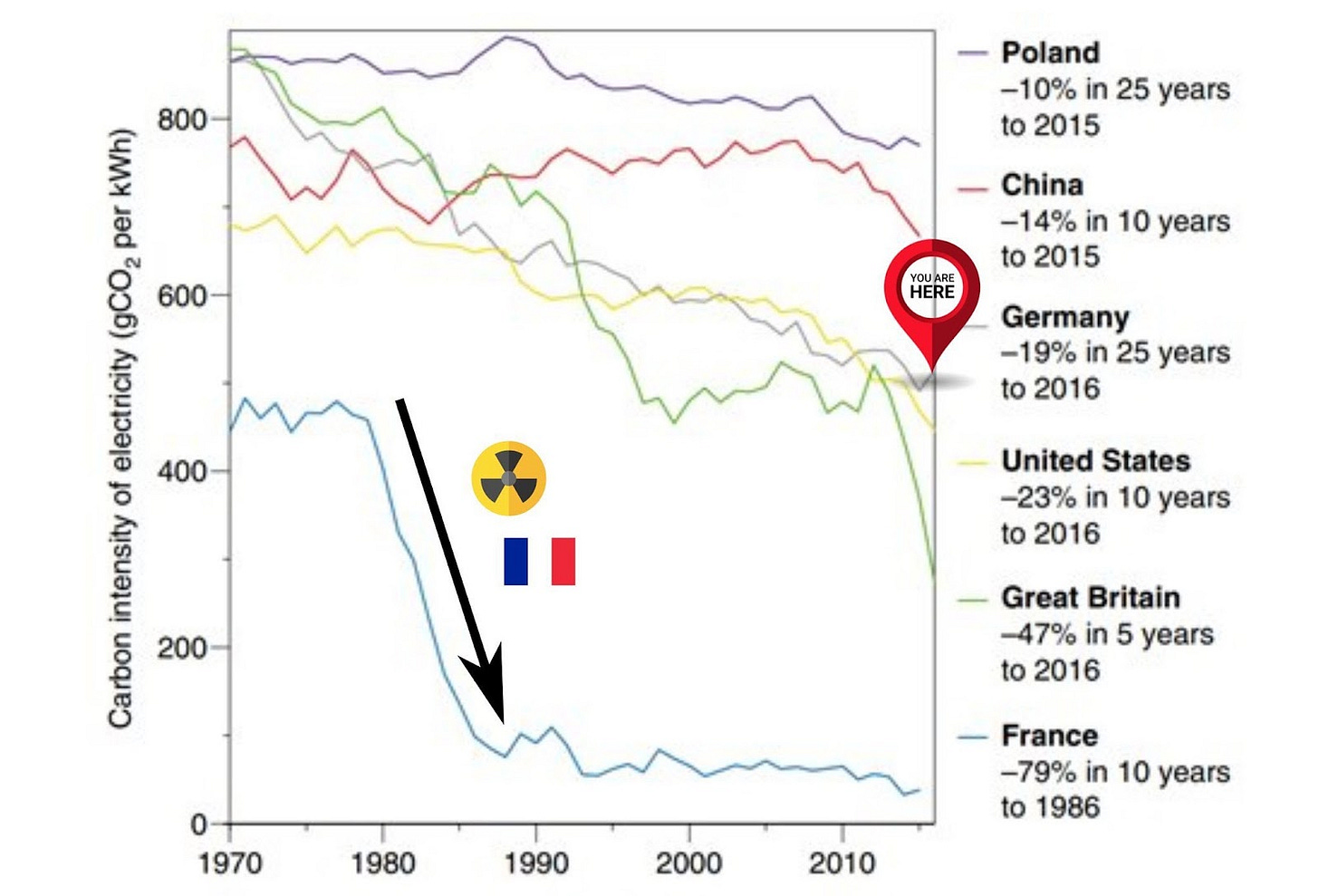

We know how to reduce resource consumption without reducing growth

It’s true that for the past 200 years, economic activity has led to an increase in carbon emissions. More recently, however, since the 1980s and largely thanks to the use of nuclear energy, many countries have been able to reduce emissions while continuing to increase GDP. Investment in renewables has also driven this growth further. In 2016, 70 countries experienced a growth in GDP while also experiencing a run of at least five years in which emissions decreased.

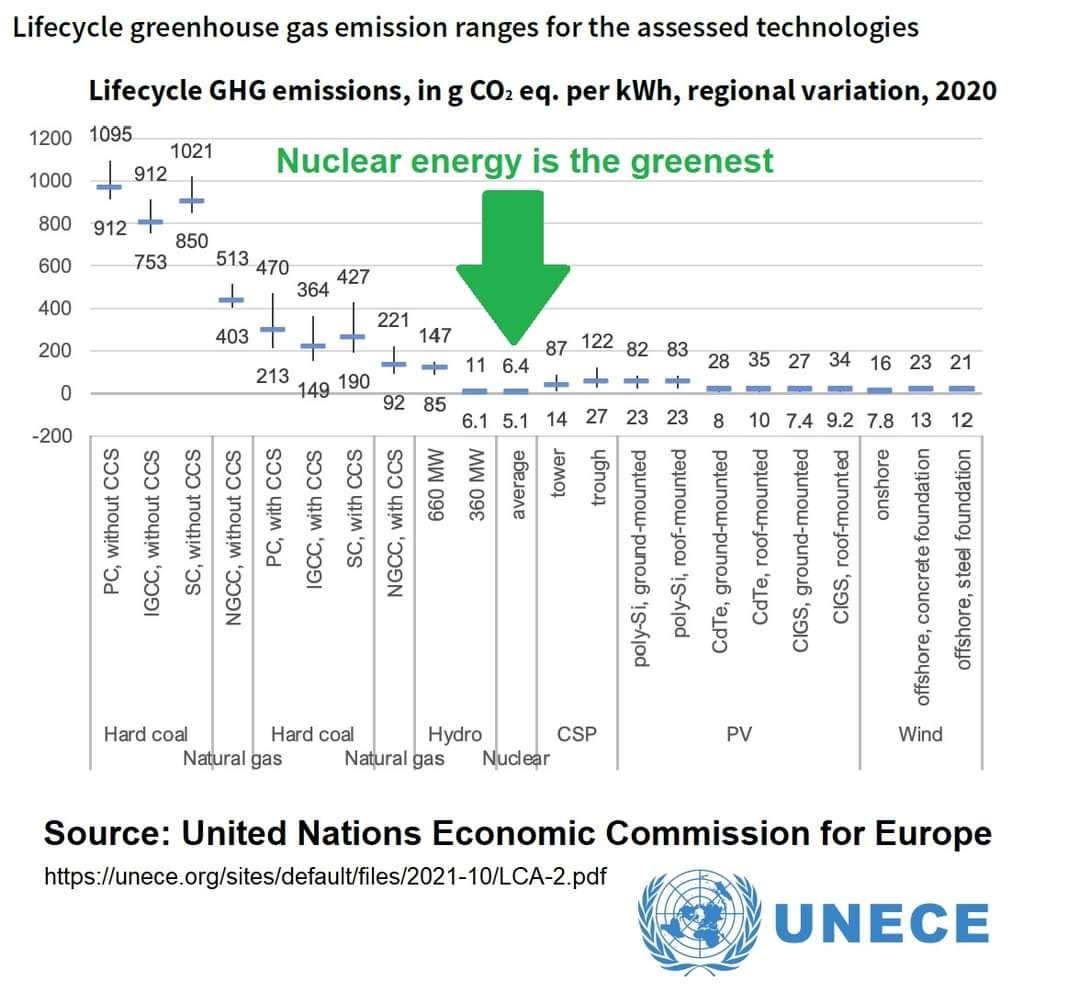

Using historical data, researchers have calculated that nuclear energy has prevented an average of 1.84 million air pollution-related deaths and 64 gigatonnes of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions. They find that:

“On the basis of global projection data that take into account the effects of the Fukushima accident, we find that nuclear power could additionally prevent an average of 420,000–7.04 million deaths and 80–240 GtCO2-eq emissions due to fossil fuels by midcentury, depending on which fuel it replaces. By contrast, we assess that large-scale expansion of unconstrained natural gas use would not mitigate the climate problem and would cause far more deaths than expansion of nuclear power.”

As countries become richer, they become more environmentally friendly. Air quality improves, water use becomes more efficient, and fewer natural resources are required. This is true across developed countries, where the population has increased but resource consumption has fallen, including timber, water, metal, minerals, and energy.

Much of this is driven by innovation and high environmental standards. There is an old saying that a parked car in the 1970s was more polluting than a modern car driving at 100mph today. This is largely because old automobile models were so inefficient and heavy, which meant that they required more fuel. Thanks to better designs and environmental regulations, even standard fuel cars have now become more efficient and less polluting. As we switch over to electric vehicles, further incremental progress will be made in this direction, particularly in reducing air pollution.

Although cars still carry an environmental cost, not having them would also have had a significant impact on the planet. The Horse Association of America calculated that 54 million acres of US farmland was spared by the automobile in the 1930s, as the land was not needed for meadows for grazing horses. The US population has nearly tripled since then, yet hundreds of millions of acres of forests were saved from being cut down to make room to feed horses and to store waste horse manure.

Cars are not an isolated example – consider your Smartphone. Again, the innovation of phone designs has significantly reduced material use. In the recent past, a single person would have owned a GPS device, a calculator, a camera, a landline telephone, an alarm clock, and so on. Now, you only need one device instead of all of these items. Yes, phones still require resources, but the amount required is significantly less than when multiple items are no longer needed to do the same job. Resource use often becomes significantly reduced as the technology becomes more efficient.

As well, not having to buy multiple products has made the technology cheaper, which has enabled many more people to gain access to it. In this way, technology can be a great equaliser. As more people gain access to these technologies, their quality of life improves and they can catch up with the rest of the world. For example, with a phone, many more people can now use the internet, which gives them access to a wealth of knowledge at their fingertips for the first time. This may not sound like a huge thing for those of us who are used to being able to Google anything we need at the press of a button or the sound of our voice, but for people who lack access to formal education, it is a game-changer.

Want to reduce consumption and resource use? Encourage better design through innovation, and effective environmental standards, and allow development to take place.

We know how to reduce air pollution

In low-income countries where many people rely on solid traditional fuels for cooking, such as animal dung, wood, and crop waste, death rates from air pollution are the highest in the world. Household air pollution was responsible for an estimated 3.2 million deaths in 2020, and over 237,000 of these were deaths of children under the age of 5. These fuels lead to myriad health issues, including non-communicable diseases such as stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer – especially among women and children who are typically responsible for household chores.

Only 60% of the world has access to clean fuels for cooking, but progress is being made in this area. When people attain higher income levels, they can make the switch to cleaner non-solid fuels such as ethanol and natural gas, which improves air quality significantly.

Almost every country in the world has made progress in tackling indoor air pollution, and global deaths from indoor air pollution have declined significantly since 1990. Despite continued population growth in recent decades, the total number of deaths from indoor air pollution has still declined. That’s thanks to increased wealth.

Outdoor air pollution is also hazardous to our health and the environment, but it has likewise improved over our lifetimes. Due to air pollution, British men born in the 1980s who were from the most coal-intensive parts of the country were, on average, almost an inch shorter as adults than those who grew up with the cleanest air. Now, thanks to a raft of national and European legislation to tackle pollution, researchers found that over 40 years, total annual emissions of fine particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, and non-methane volatile organic compounds in the UK all reduced substantially. According to the study:

“Mortality rates attributed to PM2.5 and NO2 (nitrogen dioxide) pollutants that increase the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases declined by 56% and 44%, respectively, in the UK over the 40-year period. The estimated mortality rate related to pollution from ground-level ozone (O3) – which can damage the lungs – fell by 24% between 1990 and 2010, following a significant rise in the 20 years prior to that.”

There is still work to be done to improve air quality in Britain, but what we have achieved so far is not to be dismissed.

In the US, thanks to the 1963 Clean Air Act, which was further updated in 1970, atmospheric levels of sulphur dioxide dropped to levels that had previously not been seen since the first years of the twentieth century. Between 1980 and 2015, total emissions of six principal air pollutants decreased by 65%. When lead was banned from paint and gasoline, the concentration of the element in the blood of young children dropped by more than 80% between 1976 and 1999. Research found that this led to higher IQ levels in American children, less violent crime, and fewer unwanted pregnancies. Also, six common air pollutants in the US have declined by 77% since 1970, despite the country experiencing continued economic growth – during this time GDP increased by 285% and population by 60%.

Economists summarise that in the US, “changes in environmental regulation, rather than changes in productivity and trade, account for most of the emissions reductions.”

Building more clean energy is also key to cleaner air, tackling emissions, and reducing resource consumption. When it is built in Britain, the nuclear power plant Sizewell C will produce 3.2 GW of electricity. Compare this with the 2.6 GW produced by the Drax power station by burning 27 million trees every year. The alternative to building Sizewell C would be burning 33 million trees a year. That’s more than one tree per second.

Drax, which is classed as ‘renewable’ but shouldn’t be, is the UK’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide. Burning wood creates 18% more CO2 than burning coal. Instead of relying on polluting fuels that may be classified as green, we need to build nuclear power plants, which allow us all to breathe a little easier.

As a result of Germany’s nuclear power phase-out, they are now burning coal again, and a study found that the air pollution resulting from the nuclear phase-out is now killing an extra 1,100 people a year. Japan also shut down their nuclear power plants (although they recently reversed this decision), and a study found that if both countries had reduced fossil fuel power output instead of nuclear energy, they could have prevented 28,000 air pollution-induced deaths and 2400 MtCO2 emissions between 2011 and 2017.

Despite many years of active involvement in the environmental movement, I have rarely heard the words ‘air pollution’ uttered, yet it is without a doubt an important environmental concern since it impacts all life on Earth. Deaths from air pollution are largely preventable, and had we thrown our weight behind this cause sooner (instead of, for example, fighting against solutions like nuclear energy), we would have helped to save many lives as well as reduced some planetary warming.

Population growth is good, actually

Traditional environmentalism was founded based on the myth of overpopulation. In 1798, the English economist Thomas Malthus predicted that (so-called) ‘overpopulation’ would lead to famine as there would be too many mouths to feed.

He was wrong. There was no population ‘bomb’, no famine due to increased numbers of people. Instead, life improved for many millions of people, thanks to the innovation and development that they initiated. This largely relates to agriculture and the productivity of land, where labour and capital have increased more than proportionately to the increased number of humans. Thanks to agricultural improvements and technological advances, which required the input of many people and the use of many hands, we have experienced an outcome of more food rather than less. Thanks to the mechanisation of The Green Revolution, we have seen greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production, improved food supplies, and increased economic development in underdeveloped nations. Sadly, many environmentalists are still in denial about this and see such food security as a bad thing.

Although land use and deforestation did initially intensify to feed more mouths, we have likely now passed this level of ‘peak deforestation’. Improvements in crop yields mean that the per capita demand for agricultural land has been steadily falling – since 1961, the amount of land used for agriculture increased by 7%, while the global population increased by 147%. Lab-grown meat is likely to have a further significant impact on reducing the amount of land we need to raise livestock. With great innovation comes great environmental benefits.

There is an argument to be made that increased population has led to more environmental progress, through greater human capital. In November 2022, the world’s population hit 8 billion. Across history, exceptional people have led us to technological and cultural masterpieces. The past 200 years have shown exponential growth in technical development and innovation. In 1823 there were just over 1 billion people in the world. We now have 8 billion people from whom pioneering new science, art, medicine, and other technologies are emerging daily. A bigger pool of human capital is therefore not inherently a bad thing, but may yield immense benefits – so long as many of these people are also freed from the chains of poverty so that they can live fulfilling lives and contribute to global progress.

I cannot make this argument more clearly than the late statistician Hans Rosling, who gave a talk on the reduction of extreme poverty, where he also goes into the difference that owning a washing machine made for his (financially poor) family:

“My mother explained the magic with this machine the very very first day. She said, ‘now Hans, we have loaded the laundry, the machine will make the work. And now we can go to the library. Because this is the magic. You load the laundry, and what do you get out of the machine? You get books out of the machines. Children’s books.’ And mother got time to read for me. She loved this. I got the ABCs, this is why I started my career as Professor, when mother had time to read for me. And she also got books for herself, she managed to study English and learn that as a foreign language… We really loved this machine. And what we said, my mother and me, ‘thank you industrialisation. Thank you steel mill. Thank you power station, and thank you chemical processing industry that gave us time to read books’!”

Imagine a world with fewer people like Hans Rosling in it. It would be a much poorer world without such invaluable contributions to human knowledge and progress. We would all be impacted by this loss.

Some people argue that humans have caused climate change and environmental damage, and therefore humans are the problem. This is a very black-and-white, misleading way of looking at the world. Humans are also able to solve these problems and have done so in many cases, whether through reducing deforestation, saving species from extinction, or working together to save the Ozone Layer. Fewer people won’t solve these problems. Collaboration, sensible environmental standards, and encouraging innovation and discovery will.

As well, larger populations are not as damaging to the environment as many people believe. When populations grow, people increasingly move from rural to urban areas, which puts less stress on the natural environment. Density and size of population also have environmental benefits, as large and highly populated cities are cleaner and more energy efficient than smaller cities, and much more so than rural areas. Cities are easier to heat, cool, and navigate, and urban homes emit less carbon dioxide than their suburban and rural counterparts.

Arguably, denser cities are also necessary for human progress, since they are hubs of transformation: research has found that metro areas that are dense with people become highly innovative, making them more productive and inventive than rural areas or suburbs.

Let’s give people a break. For too long we have been sold the myth that we should be concerned about so-called ‘overpopulation’, but this has been proven to be nonsensical fearmongering. Instead, population decline is occurring in almost every country in the world, and it is already having negative impacts on ageing populations and the future generations who have to support them. Not only do ageing populations impose costs on society as we struggle to pay for healthcare and pensions, but in some countries like Japan there simply aren’t enough younger people to physically support older generations, which poses serious problems for the country.

In Japan, a combination of robotics and AI are helping to balance the need for caregivers in homes with hundreds of elderly people where there are only a few human members of staff. Innovation in this area is likely to help solve the problem, as other nations seek to replicate the support system that Japan is developing (since many of us are not far behind on the underpopulation curve). But it’s telling that underpopulation has not led to a moral panic the way that false ideas of population growth have done so for many years. Arguably, underpopulation will have a far greater and more negative impact than the old worry of having more mouths to feed. For example, China, whose economy has long benefited from the sheer number of people in its workforce, is forecast to lose almost half of this population by 2100, plunging from more than 1.4 billion to 771 million inhabitants. Many of our goods come from China – including solar panels. The Chinese One Child Policy, which was so concerned with ‘overpopulation’, has proven to be short-sighted and damaging in ways that Chinese leaders did not foresee. Unfortunately, Germany, South Korea and Russia are not far behind on the underpopulation trajectory, and Europe's population as a whole will begin to decline as early as this decade.

Population growth was never really the problem. Lack of foresight, and forming policy based on myths over data, have been the real problems for the planet.

We know how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

I’ve already covered the planetary and health impacts of replacing fossil fuels with clean energy, and shown that replacing fossil fuels with clean energy is a no-brainer.

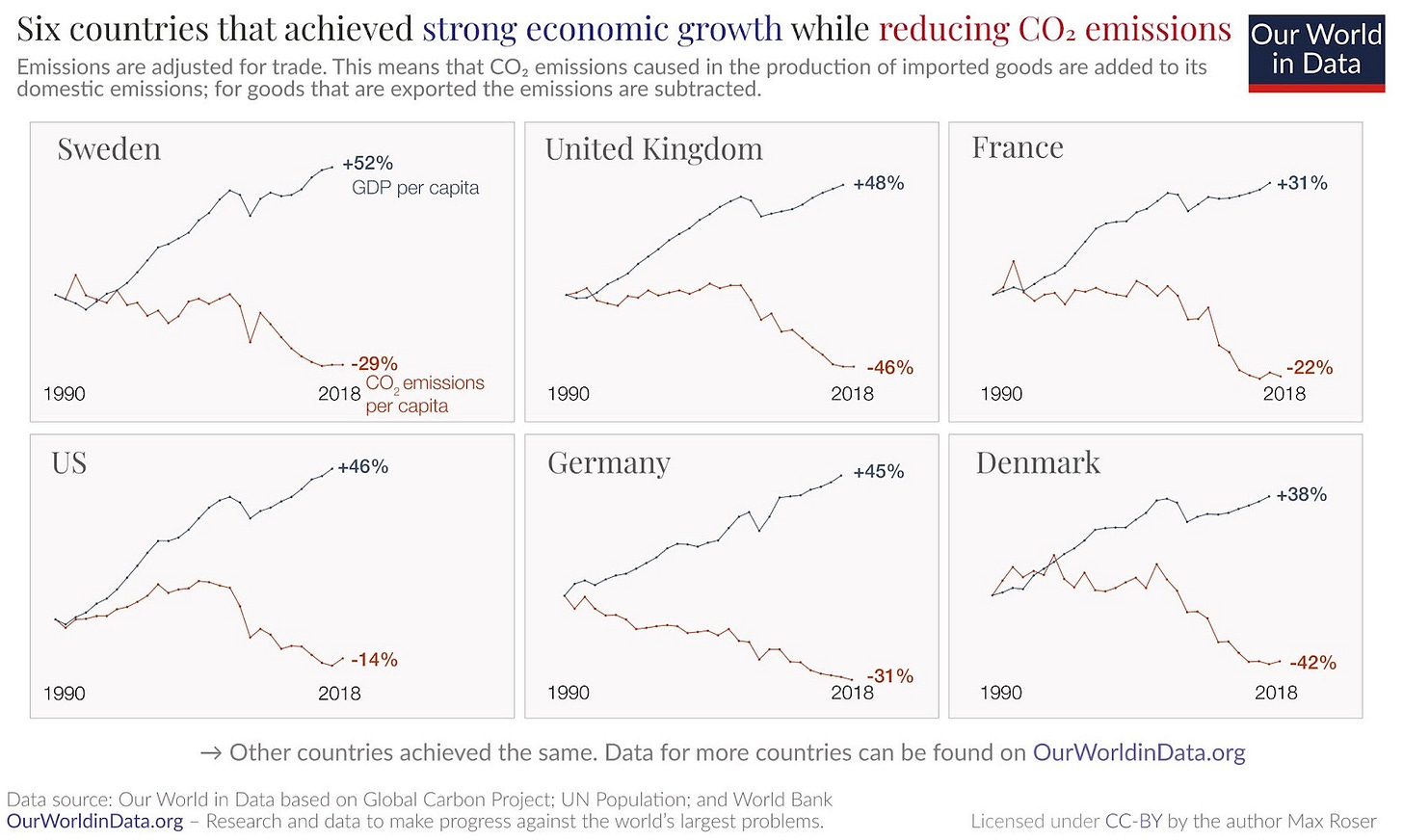

Some naysayers disbelieve the data. They argue that the reduction in emissions in rich countries is due to offshoring production overseas, i.e. transferring emissions to manufacturing economies such as China and India, but this is not true. Consumption-based emissions, which adjust for emissions from goods that are imported or exported, have also fallen. Although some emissions have been exported overseas, they are not as significant as people assume. Much of the emissions are still terrestrial growth (i.e. from within national borders). Economic growth has been decoupled from emissions in 32 countries with a population of at least one million people.

As data journalist John Burn-Murdoch writes, “There has long been an assumption that developing countries would have to go through dirty growth. But here again the data paint a promising picture. While developing countries do follow an environmental Kuznets curve, where the carbon-intensity of GDP increases before falling away again, each successive cohort traces a cleaner path than the last.”

The trend is this: countries chase economic growth and development to escape poverty, they become wealthy, then their attention turns to air quality and environmental concerns, so they set environmental standards and they transition to cleaner technologies. Therefore, they reduce their emissions and impacts on climate change and air pollution naturally. Decoupling through growth is the norm, not the outlier. It would therefore be inimical to environmental concerns to try to prevent it.

Poverty is the greatest polluter

Another question I am often asked is: can the world afford to allow countries like China and India to develop?

Sometimes I have to bite my tongue. Who are we trying to save the planet for, if not for all the life that inhabits it – including human beings?

I have already demonstrated that development does not harm the environment, once it reaches a certain point. As former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi once said, “Are not poverty and need the greatest polluters?”

Some people argue that we should avoid the potential environmental dip it would take to get to this point and that that is a cost that humankind must pay. I urge these people to think again about what they are saying, and the lack of humanity in that approach. For many years now I have argued that poverty must be considered when looking at environmental issues. I take issue with environmentalists who argue that poorer nations cannot develop, or that poverty is a better, more natural, or somehow idyllic way of life. It is not.

When people choose to escape poverty, they burn a lot of fossil fuels, which have a carbon and planetary footprint, but once people have attained a high quality of life, they turn to environmental concerns and can reduce consumption and produce fewer emissions. Logically speaking, people are not going to stop trying to improve their lives just because wealthy people (and if you have a high quality of life, that means you) tell them to. Logically, if environmentalists are genuinely concerned about the environmental impact of development, they can help to ensure that such growth happens efficiently and without delay so that environmental standards can be put in place sooner rather than later. This means that instead of fighting growth and finger-pointing at developing countries, we should focus on fighting for clean energy to be built at home – and that means advocating for nuclear energy.

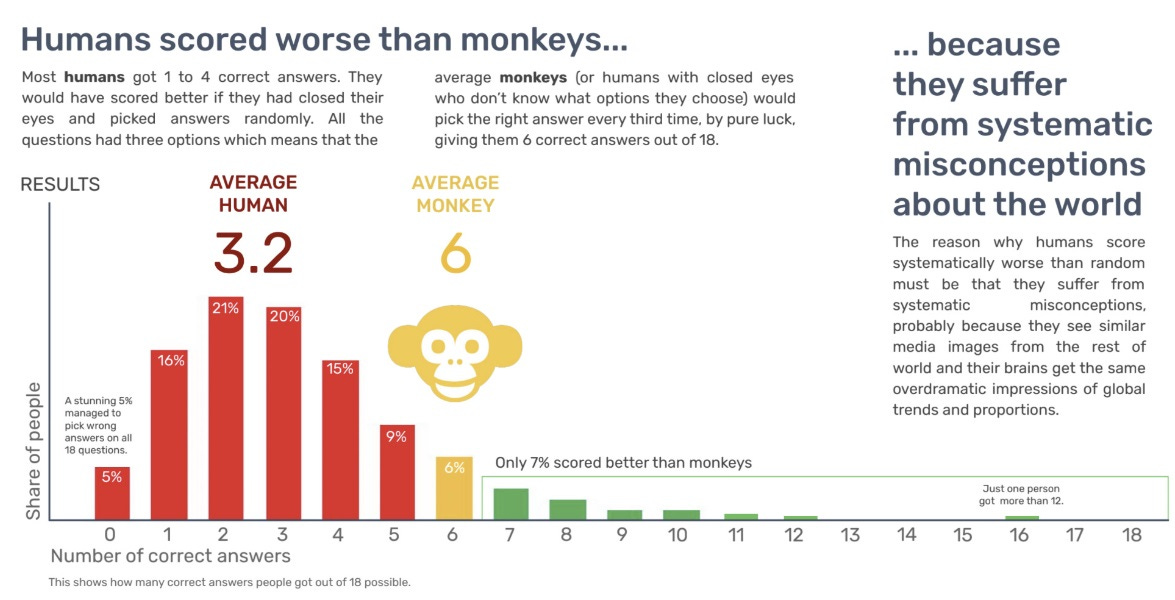

There’s still time… To stop being a monkey

Other questions I am often asked after my lectures are whether we are ‘doomed’ and how long the planet ‘has left’. I can only emphasise that while activists may have popularised ideas around there being only four or ten years left for humankind, these are made-up estimations. There is no scientific consensus of a ‘tipping point’ or point of no return for the planet (and no, rogue scientists making such predictions do not count). As well, the Earth will go on with or without us, even if we have to experience the slow change of its climate, and even if the climate becomes more like that of Venus.

Remember that people once believed that the Ozone Layer was beyond repair. It was the environmental panic of its time, with many environmentalists arguing that the end of the Earth was nigh. Instead, after nations came together to adopt the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer in 1987, around 99% of ozone-depleting substances were phased out and – unexpectedly – the protective layer above Earth began to repair itself. The Antarctic ozone hole is now expected to close by the 2060s, while other regions will return to pre-1980s values even earlier. Thanks to these measures, every year an estimated two million people are saved from skin cancer. Also, a study found that without the Montreal Protocol, carbon would have been stored in plants, vegetation, and soil – which likely would have led to an additional 0.5–1.0°C of global warming.

Evidence shows that we are capable of solving the world’s problems. The fool’s trick is to make out that predicting an apocalyptic future is somehow smarter than pointing out optimistic scenarios; when in reality, being pessimistic is simply the easier and lazier option thanks to human negativity bias. Yet many factors, some of which I have covered here, show that in many areas we are on a positive trajectory.

We are capable of decoupling growth from emissions. We are capable of improving air quality, which makes us healthier and makes our children taller, less violent, and smarter. We are capable of tackling climate change as well as eradicating poverty. We are capable of hitting net zero targets – as I wrote in a recent article, we may even be on track to keep under 1.5°C of warming. No one is going to shout any of this from the rooftops; it is not headline-grabbing news. But humans are capable of solving immense problems, including problems we have created, and we have been doing so for many years now. To place all our bets on failure does humankind a disservice; but also, no one has ever fixed a problem by fixating only on the problem. Let’s fight to implement evidence-based solutions instead so that we can build the cleaner, healthier world that we are all so keen to live in.

Once that’s taken care of, who knows what we can achieve next?

Well done. I have argued the same –

Prosperity follows energy – more energy more prosperity

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy-use-per-capita-vs-gdp-per-capita?yScale=log

1. First people want more energy

2. Initially, dirty energy (wood, coal) is cheap and does promote prosperity

3. Then prosperity allows transition to clean energy: Nuclear, Hydro, Geothermal

Thank you for this detailed article. It's very frustrating having to explain to people things like "poverty is bad" and "people are good"