What if Germany hadn’t phased out its nuclear power plants?

New research paints a damning picture

I snapped this photograph in Berlin on the day that Germany shut down its last reactor in April 2023. It depicts a Greenpeace installation celebrating the demise of German nuclear energy, with nuclear represented as a (nonsensical metaphorical) dinosaur and solar power as the hero on top, wielding a sword and shield. By any interpretation, this artwork’s message is that solar power has won.

However, by any logical measure, and according to new data, nothing could be further from the truth. Little of this celebratory atmosphere is visible today in German politics, as on 6 November this year, the ruling coalition in Germany collapsed during a debate over the 2024 budget. What happened? The chancellor said he lacked trust in Finance Minister Christian Lindner, who heads the Free Democrats (FDP). They are part of the coalition alongside Chancellor Olaf Scholz's Social Democrats (SPD) and the Greens, which means they need to agree on significant decisions like this for their parliamentary democracy to function.

Why has the German government imploded over the debt brake? Lindner said the chancellor's demand to suspend it to take on new debt would violate his oath of office. While this is not strictly true, the matter is complicated. In short, they are out of money but still have costs to pay, including for the continuation of their solar-and-wind energy transition, Energiewende.

This leads us to the elephant in the room: Germany’s disastrous energy policy. In the debate, Scholz and the Greens called for the declaration of an emergency, blaming it on the consequences of the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis. Still, no one pointed out the continuous immense financial burden of Energiewende.

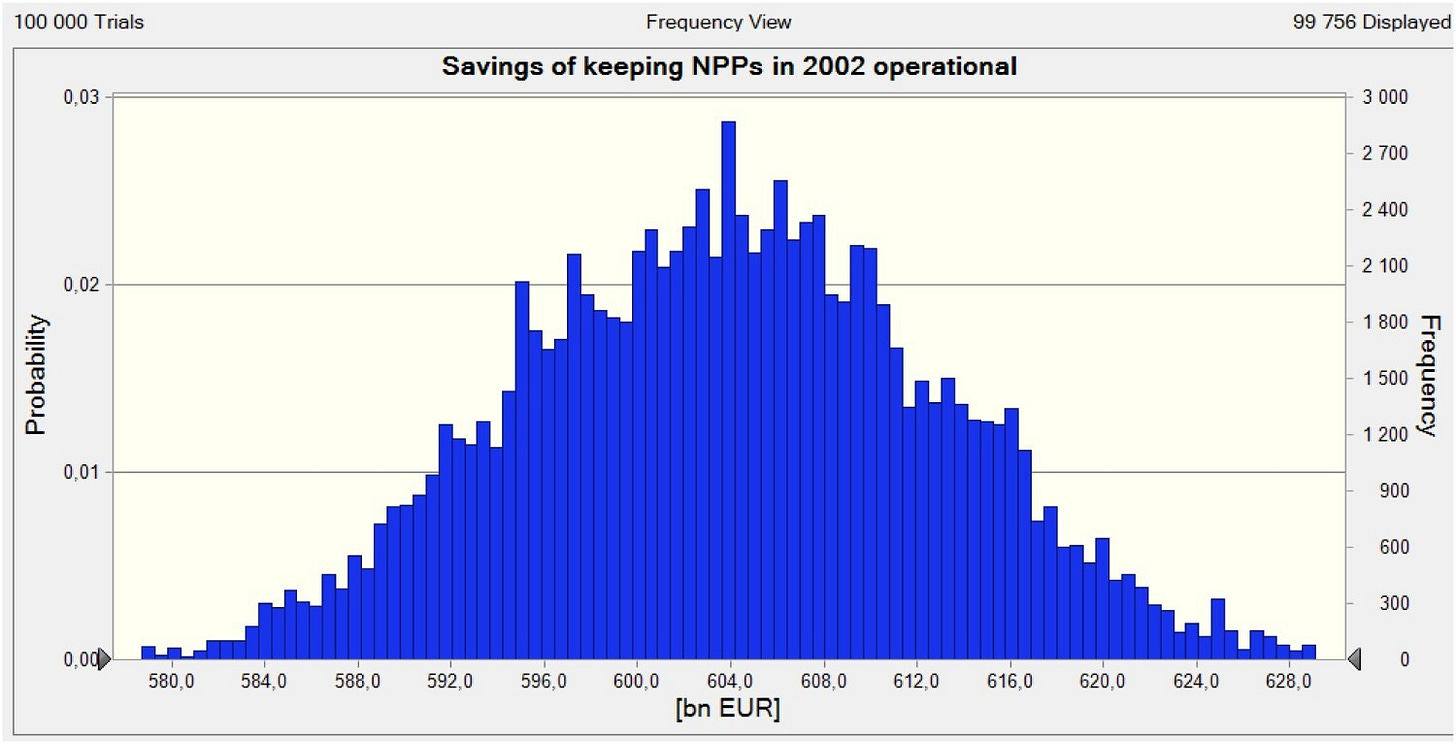

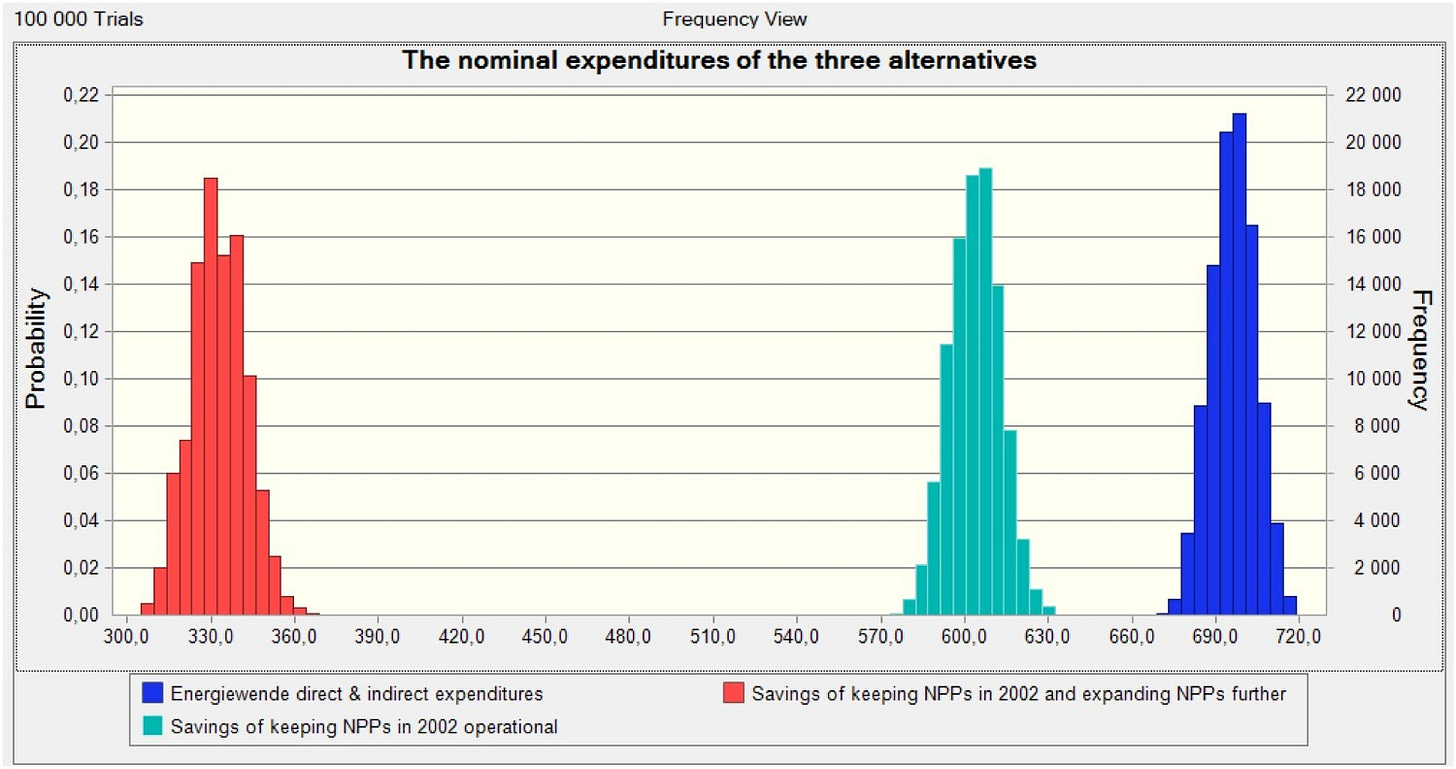

Nor has the mainstream media in Germany been covering it widely. Yet a recent paper by Jan Emblemsvåg published in the International Journal of Sustainable Energy has put the cost of Energiewende at almost €700 billion. That includes €387 billion in investments and €310 billion in subsidies. The researchers summarise that:

“By contrast, if the country had kept its existing nuclear plants operational and invested in new reactors, the estimated cost would have been only €36 billion, significantly less than the Energiewende policy.” Tell me again that you think nuclear energy is too expensive.

If these costs come as a surprise, read my breakdown on how people often get cost estimates in the energy sector wrong.

Many of us have been waiting with bated breath to see whether Germany will U-turn on nuclear energy. According to the latest polls, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), led by Friedrich Merz, is expected to win the snap election on 23 February. He disagrees on energy and climate policy with his most likely coalition partner, Scholz. The CDU may want to explore the possibility of restarting the country's nuclear power plants, but Scholz’s SPD is still wedded to the idea that restarting nuclear is too expensive. Someone will have to compromise. It remains to be seen whether this will be Scholz or Merz. Merz has argued for greater openness to technology in an interview with DW, stating that:

“We phased out nuclear energy − some 12 years ago − and yet we still don’t know what we will replace it with...This mindset, where we start at the level of highly ideological discussion, doesn’t appeal to me. It is reckless of us to don blinkers. We end up excluding technological developments that we are not even aware of yet. The economist Friedrich August von Hayek called this the pretense of knowledge. A very good term for it. Would we still decide to phase out nuclear energy today? We can be fairly sure we wouldn’t. Was it right for Germany to ignore the dual fluid reactor and allow its purchase by Canadian investors? Again, probably not.”

Merz may decide that the damage is irreversible, since restarting German nuclear will require finances the country doesn’t have. Still, both parties are committed to Germany reaching a net zero target by 2045, for which they will need to put nuclear back on the map. Emblemsvåg’s paper shows that if Germany had retained its nuclear fleet, it could have achieved a 73% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by now, instead of the measly 25% it did attain - and at half the cost. In addition, Energiewende has resulted in high energy prices for German citizens and manufacturers, which has contributed to deindustrialisation through companies moving abroad. The direct result is a faltering economy with over €696 billion in expenses, increased reliance on energy imports, weakened energy security, and political uncertainty.

The study also highlights the role ideology played in German energy policy, which I believe was buoyed by bias and energy-illiterate journalists (although yours truly did her best to draw attention to the pitfalls of phasing out nuclear energy. There’s no excuse: experts repeatedly warned German politicians not to phase out baseload power entirely, but they were ignored.

Germany is not the only country that has made mistakes with energy policy, but it is a cautionary tale for others attempting to meet net zero targets. Surprisingly, some are still attempting to copy Germany, for example, Australia maintains its ban on nuclear energy despite growing opposition to this archaic rule, as the Australian government want to meet its energy needs with mostly wind and solar power, with a little gas as baseload. Although we don’t have a ban on nuclear energy in Britain and we should have two new plants online before the end of this decade, the Labour government is also mostly placing its bets on wind and solar (but let’s not just blame them, as the Conservatives who held power for 14 years before them did not announce any new nuclear power plants).

Emblemsvåg’s paper concludes that “regardless of uncertainties in data and assumptions, there can be no doubt that if the political environment in Germany had been favourable to NPPs in 2002, the country would have fared far better than with the current Energiewende both concerning expenditures and climate gas emissions.”

Collectively, the world has blundered. A few years ago, I was heavily attacked for saying in an interview that if so many countries had not phased out nuclear energy or imposed bans on it, climate change wouldn’t be as much of a challenge as it is today, as global emissions would be lower. Hate to say I told you so, but there is now undeniable evidence to back that up. A new report has found that had nuclear power plants not been phased out globally, “Last year, global energy-related emissions would have been 6 per cent lower, saving 2.1 Gt of CO2. This would be the same as taking about 460 million cars from the road for a year or removing the combined total 2023 emissions of Canada, South Korea, Australia and Mexico.”

The fact that politicians made these decisions under the guise of environmentalism is perhaps the most bewildering of all, since the data is clear that nuclear is environmentally superior. The remaining lesson is incontrovertible: replace rationality with vibes and the pretense of knowledge, and it will cost you financially, economically, and may even lead to political instability. Choose to transition a functioning energy system to intermittent, less efficient alternatives, and sooner or later, we all pay the price.

Germans were once viewed as smart & wise.

Greenpeace, by the way, doesn't reveal its funding, especially from the petro biz.

Thank you for an excellent analysis. South Africa is also on a risky policy road to 'Net Zero', with government increasingly committing to wind and solar in an apparent attempt to emulate Germany. Fortunately some reality has been forced on government by a period of electrcity supply shortfalls, , euphemistically termed 'load-shedding'. This has resulted in a delay in the planned shuttering of coal-fired power stations (80% of our electrcity comes from coal), and new interest in nuclear. South Africa has one French-designed nuclear power station (Koeberg in the Western Cape) that has been running well since 1984. The country also made sigificant progress on its home-grown SMR, the PBMR project, and we have a pilot plant that successfully produced pebble fuel. The project was closed around 2008 for financial reasons as well as lawfare by the local anti-nuke activists. There is talk of trying to revive the PBMR project, but this is unlikely to happen. The skilled PBMR ex-peronnel are now scattered around the globe, with some leading experts with X-Energy in the USA. A large contingent of South Africans worked on the new nuclear plant in the UAE. ' Climate catastrophe' rules the media waves in South Africa and contrarian views get no mention at all. Keep up your good work. John Ledger.