When I was a student I was part of a campaign group that fought for, among other things, clean energy on campus. We collected signatures outside the Students’ Union to petition the Vice Chancellor to switch to a clean energy provider. We decorated the lawn in front of the Students’ Union with tiny paper wind turbines to drive home our point.

“Switching to a renewable energy supplier is one of the easiest and most environmentally-friendly things you can do,” I used to tell people. I still think that’s true. What was incorrect was the definition of clean energy I was using, because I now know that the term ‘renewables’ is meaningless.

‘Renewables’ encompasses hydropower, wind power, solar power, geothermal, biomass, and biogas, but these are vastly different types of energy generation, with varying degrees of environmental impact and efficiency.

For example, wind power and solar power, generated by wind turbines and solar panels, are technically clean energy sources because, unlike fossil fuels, they do not emit greenhouse gases (GHG) to provide us with energy (to be pedantic, they do emit GHG during construction, but this is true of all types of energy generation). Wind and solar are also intermittent energy sources, which means that they require battery storage to meet significant energy needs, and even with storage they still require a baseload, or backup power, when it isn’t windy or sunny. This baseload power is provided by either fossil fuels or nuclear energy, except where hydropower is available.

Hydropower is in some ways exceptional because it is powerfully efficient, but it is also only available where it is geographically viable to construct large dams.

Wind and solar differ from hydropower, biomass and biogas, as the latter three can provide 24/7 reliable energy.

But biomass and biogas are deeply problematic.

Biomass: a burning issue

Traditional biomass - the burning of organic wastes, charcoal, and crop residues - was a key energy source for a long period of human history.

While it is true that biomass is biological material derived from living or recently living organisms, and is therefore as ‘renewable’ as wind or sunshine, it can also be heavily polluting. UK government research found that greenhouse gas emissions per unit of electricity generated from biomass can be higher than those from fossil fuels like coal or gas.

Drax Power Station is a large power plant in England where biomass (wood pellets) are burned to generate electricity. In 2017, greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of biomass for electricity production in UK power stations were around fifteen million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. According to the UK government, emissions from biomass “are also reported as a memorandum item in the country and sector where the biomass fuel is used, but unless domestically grown are not counted in that country’s total emissions.”

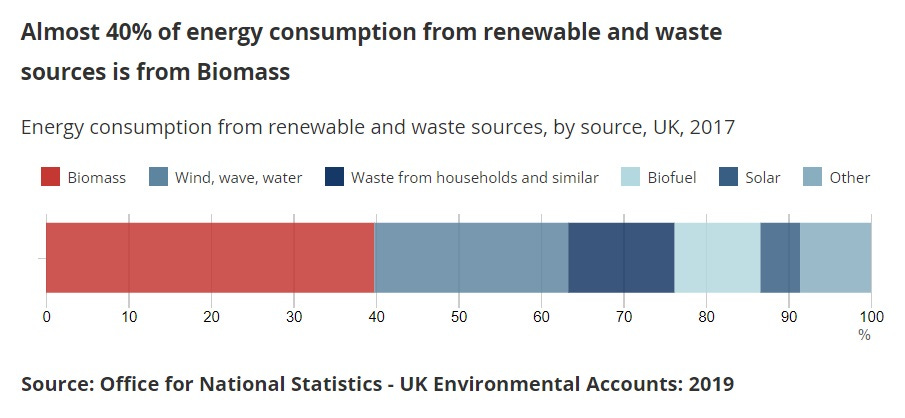

Biomass also confuses statistics for emissions by forming the bulk of the figures for renewables around the world. For example, in the UK, biomass is the biggest source of ‘renewable’ energy consumed, and the main source of biomass burnt in UK power stations is wood pellets. This means that while it looks good that countries are investing more in renewables, the reality is that they are burning trees to do so.

In a letter signed by 650 scientists, they argue against the use of biomass:

“Troublingly, because it has wrongly been deemed ‘carbon neutral,’ many countries are increasingly relying on forest biomass to meet net zero goals. This is harming our world’s forests when we need them most. Many of the wood pellets burned at power stations for bioenergy are coming from whole trees — not wastes and residues from logging, as the industry claims. For example, nearly half of all biomass burned at the UK’s Drax Power Station comes from whole trees.”

Most of the wood burned at Drax is imported from North America. According to The Guardian, Drax is seen as essential for “when weather conditions preclude significant wind and solar power generation.” Drax also receives government subsidies.

To meet renewables targets, governments are investing in more renewables, but not necessarily making the best decisions to decrease emissions. This is because the term ‘renewables’ is incorrectly being used interchangeably with ‘clean energy.’

‘Renewable’ does not mean ‘clean’

I didn’t realise when promoting renewable energy companies to my peers that those companies often rely on biomass and even fossil fuel backup to meet household energy needs. While this could be fine as an interim measure for them to shift toward a renewables-only supply, for many companies this shift has not taken place since I was a student.

A report by UK consumer champion Which? found that only forty suppliers out of the 300 energy tariffs they analysed sold 100 per cent renewable energy, although many more claimed to. Which? argues that greater transparency is needed around how ‘renewable energy’ is defined and marketed to ensure that customers aren’t misled, as a third of people purchasing a renewable tariff thought it meant that all of the electricity delivered to their home was from renewable sources.

The report found that companies including Green Star Energy, Ovo Energy, Pure Planet, Robin Hood Energy, So Energy, Tonik Energy, and Yorkshire Energy claim to sell ‘100 per cent renewable’ electricity tariffs, but they do not generate renewable energy or buy it directly. In the UK, these companies buy Renewable Energy Guarantee of Origin (REGO) certificates to show customers that a given share of energy was produced from renewables. REGO certificates are cheap, but these tariffs do little to encourage the generation of renewable energy at home. Similar schemes operate in Europe and the US.

The certificates system also has a loophole that allows energy providers to double count the UK’s renewable energy supply use, or claim foreign renewables as their own.

Many larger electricity suppliers own or have partnerships with a mixture of renewable and fossil fuel generators. Their green tariff may be backed up by the REGOs from their low-carbon electricity sources, but their standard tariff often provides electricity from a mix of sources, which means that the company is not completely fossil fuel-free like it may be claiming.

This means that when I was asking people to switch to renewable energy companies, I was often encouraging reliance on the thing I was against - continued dependence on fossil fuels.

Biogas: an amazing solution, or a load of hot air?

Biogas, or biomethane, is produced when organic matter such as food scraps, crops or animal waste is broken down by microorganisms in the absence of oxygen. This process is called anaerobic digestion (AD). Bacteria consume the waste products and release methane, which is captured on farms inside air-tight containers known as digesters.

Despite offering a promising renewable energy supply, biogas plants are often the source of significant methane emissions. Research has found that “despite efforts taken to reduce global greenhouse gases, methane emissions continue to rise largely due to the growing use of biogas as a renewable energy resource.” Biogas plants may, account for up to 1.9% of total methane emissions in the UK - enough to threaten net zero targets.

In the US, there is significant debate over whether ethanol, biomass, and biogas are better for the environment than fossil fuels, as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently proposed increasing them under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). The RFS aims to increase renewable fuels by around nine per cent by the end of 2025, with a target of roughly twenty-one billion gallons of renewable fuels in 2023, including over fifteen billion gallons of corn ethanol. By 2025, the EPA hopes to have over twenty-two billion gallons of different renewable fuel sources powering the nation.

The biogas industry has grown significantly in the US over the past two decades, mainly thanks to California’s 2006 Low Carbon Fuel Standard for ‘low-carbon and renewable alternatives’ to gasoline and diesel. According to the EPA, electricity generated from biogas more than doubled between 2010 and 2020. Now, the biogas industry is about to get even bigger thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, which will give tax credits of up to thirty per cent to biogas facilities that are built in the US by the beginning of 2025.

Again, the devil is in the details. There is a vast difference between biogas that is created using waste that is already breaking down, and growing crops like corn specifically to create biogas, which also creates more methane. The latter is a shockingly common practice because yields of biogas are low unless crops grown solely for energy production are used. The former is still polluting, but at least it uses material that is already decaying.

In 2014 British environmentalist George Monbiot wrote that “the area of maize being grown for biogas in the UK has trebled to 15,000 hectares in the past two years alone, and is likely to rise to 25,000 hectares next year.” He also outlined the environmental harm of growing so much maize, including significant land use, increased flooding, soil loss and erosion, siltation, and the need for more fertiliser and pesticides to grow the maize, which pollutes rivers and streams through runoff.

Monbiot’s predictions were correct: according to UK government data:

“Of the feedstocks used in operational plants in 2019/2020, 34% were crop derived (approximately 4.7 million tonnes). The vast majority of this (4.2 million tonnes, 30% of total feedstocks) was crops purpose grown for biogas. It is estimated that crop feedstocks required a cropping area of 93 thousand hectares in the UK in 2019/20 … In June 2020 the area of maize being grown for AD [anaerobic digestion] was 75 thousand hectares. This is an increase of 12% compared to 2019 and equates to 34% of the total maize area in 2020 and 1.3% of the total arable area.”

In Germany, crops grown solely for energy production have played an important part in the rise of biogas production. Germany has the highest number of biogas plants in Europe, and of the energy crops used for the production of biogas in Germany, maize crops account for 69%.

In 2012 Der Spiegel reported that: "Subsidies for the biogas industry have led to entire regions of the country being covered by the crop … What resulted was a revolution in the fields, a subsidised gold rush – and an ecological disaster. Corn [maize] is now being grown on 810,000 hectares in Germany." Because of this, the paper reports, "for the first time in 25 years, Germany couldn't produce enough grain to meet its own needs."

It isn’t easy being clean

According to Which? the energy companies that qualify to be ‘Eco Providers’ are Good Energy, Ecotricity, and GEUK, because out of all the companies selling renewable energy, they are the three that provide 100 per cent renewables. However, this terminology of ‘renewables’ includes biogas. Good Energy sells 10% biogas, Ecotricity sells 1% biogas which they call ‘vegan energy’ because they only break down non-animal products, and and GEUK sells 100% biogas and also offers tariffs that include biomass. GEUK does clarify that the biogas from one of its tariffs comes only from waste materials, not from specifically-grown crops.

Which? found that these companies also have some of the most expensive tariffs on the market. This means that people are paying extra money assuming that they are helping the planet, but are in some cases being misled about what their money is funding.

Depending on how it is made, biogas may not be as polluting as fossil fuels, but greater transparency is needed regarding how it is sourced and to ensure that their biogas is not classed as clean if it relies on specifically grown crops that require - and damage - a lot of land. After all, that is meant to be the point of switching to renewable energy.

How we talk about solutions to climate change is important. We need to use clear and accurate terms if we truly want to tackle climate change and air pollution effectively.

Unfortunately, the debate about biomass and biogas has not extended to consider a clean energy source that has the smallest land footprint and the most well-managed waste of all types of energy generation: nuclear energy. This bias is costing us lives and damaging our planet - simply because nuclear energy is not technically classed as renewable.

Inaccurate terminology has consequences

The problem is, and has always been, the focus on ‘renewables’ instead of low-carbon energy.

When I was campaigning for renewables as a teenager, I genuinely believed that it was the cleanest, most efficient solution with the lowest environmental impact of all energy sources. Back then, I had no idea that ‘renewables’ was, and still is, an arbitrary term.

This confusing terminology has real-life consequences.

Example 1: Biofuels in the US

In the United States, Congress created the Renewable Fuel Standard Program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and boost the production of renewable fuels. Under this definition, a corporation in America is now planning to make biogas out of plastic. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently gave a Chevron refinery permission to create fuel from discarded plastics, which, according to The Guardian, can emit air pollution that is so toxic that one out of four people exposed to it over a lifetime could get cancer. The inclusion of biomass and biogas in the Program has led to much debate in the US over whether they should be considered renewable and financially incentivised in this manner.

Example 2: Renewables targets in France

Another striking example that demonstrates the problems with incorrect terminology is the launching of the European Union (EU) Renewable Energy Directive (RED) in 2009 with a target to achieve 40% of renewables in the EU energy mix by 2030. The RED is a binding target, and France is being fined €500 million for being the only EU member state to miss the target.

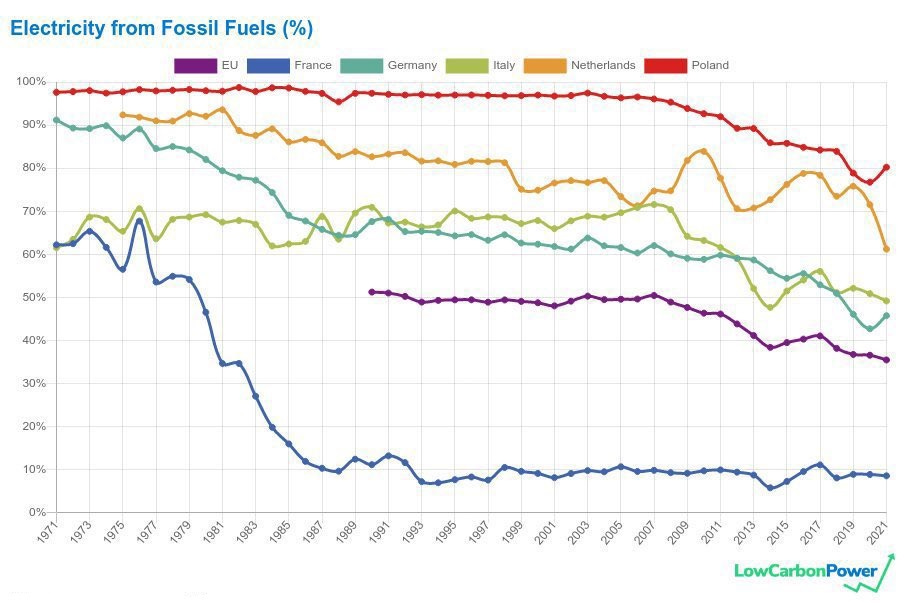

Renewables in France represent only 19.1% of its gross final energy consumption, since France has had a clean energy mix thanks to obtaining over 70% of its energy from nuclear power for decades. The country decarbonised before anyone was talking about climate action and renewables targets, and has had some of the lowest emissions in Europe since the 1980s.

Meanwhile, other countries are not being fined for their high-carbon intensity - even though some of France’s large neighbours create emissions that are six or even twelve times higher - or for burning large amounts of coal while achieving their renewables targets. There are no EU directives against this.

It seems obvious that France shouldn’t have to add renewables to the grid to virtue signal undertaking climate action, let alone be penalised for not doing so, when their energy mix is already so clean. Ironically, had France added enough biomass to their grid to meet the EU renewables target, they would not have been fined, even if it meant that they were contributing heavily to greenhouse gas emissions by doing so.

Thankfully, France is fighting back against this illogical practice by forming a nuclear alliance with other EU countries who agree that nuclear energy should be included in clean energy targets, not just renewables. The outcome of the alliance remains to be seen.

Example 3: Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by the United Nations in 2015. Sustainable Development Goal 7, Affordable and clean energy, aims to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”, with a focus on developing countries. This goal classes ‘renewable’ technologies as sustainable, while excluding nuclear energy. SDG 13, Climate action, focuses on lowering greenhouse gas emissions and adaptation to climate change, and again this goal does not mention nuclear energy.

According to multiple scientific bodies, nuclear energy is clean, reliable, and is needed to transition away from fossil fuels to combat climate change. No country in the world has been able to decarbonise its electricity sector without having either nuclear energy or - where available - substantial hydro or geothermal energy as part of the energy mix.

In my journal article examining this exclusion of a key tool in the kit to fight climate change, I found that the SDGs commit to fossil fuels over nuclear energy. SDG 7 recognises that renewables cannot work without a backup energy source, stating: “By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology.”

Rather than accept nuclear energy, SDG 7 bets on a vague future of ‘clean’ fossil fuels. The absence of clean and currently-available nuclear energy is notable here and is a bias that needs addressing if we want to wean humankind off of polluting fossil fuels.

It makes sense for nations to set clean energy targets, but only if the targets apply to all types of low-carbon energy, not just to ‘renewables’.

These examples show that the policy consequences of the arbitrary term ‘renewables’ are significant.

What is in a name?

‘Clean energy’ is generally considered to be energy that does not pollute the atmosphere, creating little or no greenhouse gases. Wind power, solar power, hydropower, biomass, and biogas are considered to be renewable because they use natural resources: aside from the initially required materials, mining and construction, they come from the replenishable power sources of wind, sun, water, and wood. This does not mean that they are clean.

One could argue that if wood for biomass is considered to be renewable then so should uranium: while uranium does not grow indefinitely, it is a naturally-occurring resource and so plentiful that there is enough uranium in the ground to last us four billion years. Arguably, due to deforestation, we could run out of wood to burn before we exhaust the world’s supply of uranium.

Some people argue that ‘renewable’ energy means that it’s a recyclable source of energy. But is that the way we want to think about trees - that the best use for them is to chop them down and burn them? Trees have even been grown specifically for that purpose. This seems like a warped definition of recycling. Again, if this is the logic being used to justify the terminology, then nuclear energy is also renewable because it can be recycled.

However, I am not arguing that nuclear energy should be considered to be technically renewable. It would be more helpful and accurate to break up the unscientific lumping together of ‘renewables’ and look at each energy source separately, especially with biomass and biogas, as their environmental impacts vary greatly depending on how they are sourced. There also needs to be greater transparency from renewable energy companies about the types of biogas and biomass they are selling.

I used to calculate my individual carbon footprint using a carbon calculator, but have since learned that renewable energy companies are considered to be clean by most of these calculators, while companies that sell nuclear energy are not. Just as with France being penalised for committing to clean energy that isn’t technically renewable, carbon calculators are giving people the false impression that renewable energy providers are always clean, and ignoring those that provide nuclear energy, which is clean.

Instead of setting targets based on the arbitrary definition of ‘renewables’, we need to set low-carbon energy targets.

As a small student campaign group, we did manage to convince our university to switch to a clean energy provider, and we celebrated that at the time. Now I realise that this isn’t the victory I thought it was when I was nineteen. If the university was with a nuclear energy provider to begin with, we may even have made things worse by persuading them to switch to a ‘renewable energy’ company that relies on biomass and biogas. I don’t make that mistake any more - I now power my home with locally-produced, clean nuclear energy.

To effectively bring down global greenhouse gas emissions, world governments and leaders need to reconsider how they power our countries too. When they do this consistently and logically, we will have real cause to celebrate. As the planet warms and air pollution from fossil fuels continues to kill millions of people a year, failing to do so would be inconceivable.

I live near the port of Wilmington NC wood pellets are shipped for here to The UK to be burned to produce electricity. I live in Southport NC at the mouth of the Cape Fear river. The wood pellets pass by our nuclear generating station on the way to the UK

Growing corn for biofuels is a great con and harmful to the globe