Stagnation, overregulation, deindustrialisation. Can Europe bounce back?

Case studies for European optimism

Stagnation, overregulation, deindustrialisation. These words are often thrown around to describe Europe, but are they accurate?

I’ve made my fair share of comments that Europe has problems, particularly regarding how the UK is a regulatory nightmare and Germany has an awful energy policy which is contributing to its deindustrialisation. But do these countries reflect all of Europe?

Before we dig in, some of you will ask what the economy has to do with the environment, so feel free to read this article as a reminder of why the answer is everything (tl;dr: as countries become economically richer, they become more environmentally friendly).

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s look at what’s happening in some of the less-discussed European countries.

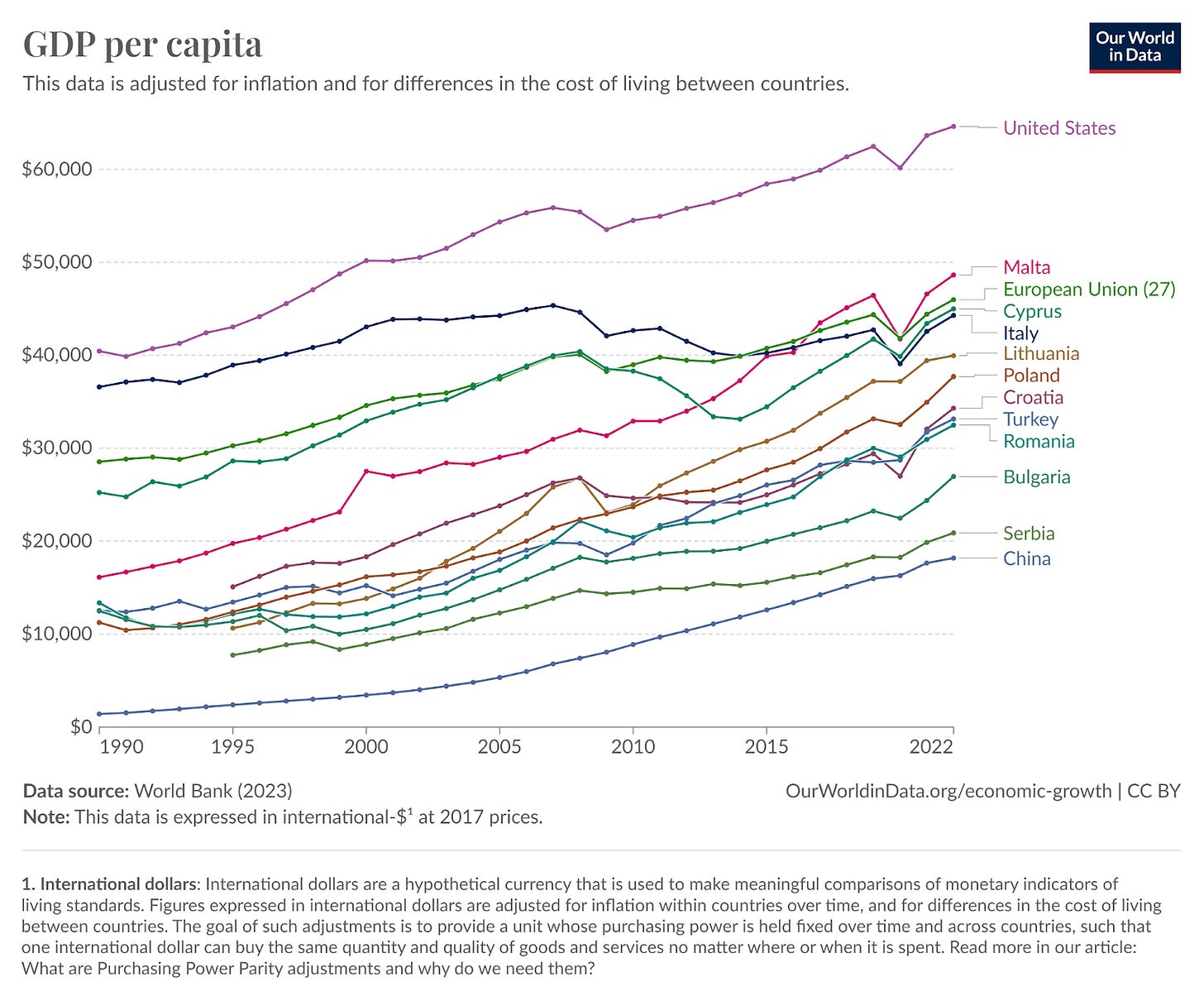

A graphic speaks a thousand words, and this one is being shared widely:

I’ve noticed Americans sharing this to demonstrate the decline of the Western world, but for that purpose, it’s wrong. Doing so is like comparing Mississippi with California and then drawing an average and deducing that the average reflects life in the US and the country’s future. Every state and every country in Europe is playing a different game, and some countries are doing significantly better than others.

By breaking the graphic down into select European countries and considering the curvature of each growth curve (which indicates the relative level of growth), we obtain a graphic that paints a more complex picture:

The breakdown shows that substantial growth is taking place in Europe, but it has shifted direction, away from some of the usual countries we tend to focus on. It’s true that some countries have lost manufacturing - I saw this directly as my parents were factory workers and before they reached retirement age all the factories in our city had shut down and gone abroad, leaving derelict buildings behind.

But other parts of Europe are still manufacturing. Consider the Southern European country of Malta, which is experiencing a boom in growth. Malta’s economy is based on tourism, financial, and other services. Malta also has considerable manufacturing exports, particularly electronics and pharmaceuticals. It’s not alone: Serbia’s economy is also thriving this year, thanks to its trade, tourism, catering, and construction services.

It’s also worth remembering that these graphs don’t represent all relevant factors, such as standard of living and quality of life. Under the latter measure, Northern European countries outshine everywhere else.

Traditional manufacturing may have moved overseas, but Europe hasn’t lost its technological progress. It’s just moved to countries that don’t get as much of the spotlight. Take Italy, which has its own “Data Valley”.

While some countries focus on developing tech capabilities, and others benefit from having politicians with foresight, Italy has both. Italy is home to some of the world’s most advanced supercomputers, including Leonardo, and the country has several tech start ups covering a variety of sectors, including energy, e-commerce, fintech and software development. One of Italy’s biggest industries is vehicle production, and Italy’s manufacturing sector accounted for 22.6% of GDP in 2021.

The Italian tech unicorn Bending Spoons has been acquiring notable companies for some time, many of which were originally in Silicon Valley. If you haven’t heard of them, the Italian government chose Bending Spoons to design and develop the country’s Covid contact tracing app, Immuni, in 2020, and the company owns the mobile video editing app Splice, which has over 4 million users worldwide.

In September this year, former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi published a report on EU competitiveness, a sangfroid manifesto to combat the "slow agony," as he puts it, that Europe is facing. He draws attention to key issues, including the need for investment in innovation, addressing the fragmentation of financial markets along national borders, and fixing the overdependence on non-European companies to manufacture and deliver core goods and services.

The report is compelling, proposing a €800 billion annual investment boost focusing on innovation, advanced tech, and decarbonisation goals that align with economic growth and stability. Draghi recognises that growth and environmental progress go hand in hand:

“Sustainable competitiveness should make sure businesses are productive and environmentally friendly… If Europe cannot become more productive, we will be forced to choose. We will not be able to become, at once, a leader in new technologies, a beacon of climate responsibility and an independent player on the world stage. We will not be able to finance our social model. We will have to scale back some, if not all, of our ambitions.”

The message is salient and hasn’t been lost on European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who is setting up a team of officials dedicated to implementing ideas from Draghi's blueprint for competitiveness. The EU President has said that the main initiative of the next five-year term will be a "competitiveness compass" to close the innovation gap with the US, decarbonise the EU economy and increase its economic independence. Some members of the task force she is appointing to the team also contributed to Draghi’s report.

What about energy? Italy will need a lot of power to fuel Data Valley and keep manufacturing financially viable. The country once had four operating nuclear power reactors, which were phased out with a referendum in 1987 and a complete ban in 2011.

In September of this year, Italy chose a different path: Environment Minister Gilberto Pichetto Fratin announced plans to introduce new regulations to allow nuclear technologies in the country, aiming to have a new decree in place by 2025. What happens next remains to be seen, but it’s clear that Italy is on the rise.

Let’s travel north and consider another underrated case study for growth: Poland.

Poland was once known for the number of people who emigrated to find work in countries like the UK and US, but now Poland is set to outstrip the UK economically by the end of the decade. What changed?

First, years of steady economic growth have allowed Polish people to return to their homeland to take advantage of opportunities that were not previously available to them. This phenomenon of educated, intelligent workers returning home is being called “reverse brain drain”. Poland already has the EU’s third largest military, but the returning Polish diaspora now also has immense opportunities in tech. Poland has been known for its top-class IT specialists for some time, and the Polish IT market is currently one of the fastest growing in Europe.

For the same reasons, fewer young Poles need to leave their country for well paid jobs and opportunities.

Second, Poland has welcomed citizens back with open arms. Britain is suffering from significant labour shortages across many industries, and following the Brexit referendum, an estimated 200,000 Polish people left the country. Britain’s loss has been Poland’s gain: the Polish government has incentivised national citizens to return home by, for example, exempting returning citizens from paying income tax for the first four years after resettling.

As well as skilled workers returning home, almost 1.5 million Ukrainian refugees with the right to work in Poland have added their skills to the Polish workforce.

Third, Poland is welcoming a substantial tech boom. For some time, the multinational tech company Amazon has boasted of the fecundity of its investments in Poland. In 2020, Microsoft announced a $1 billion digital transformation plan for Poland to accelerate innovation and digital transformation in what people now call the “Polish Digital Valley”. The seven-year plan includes opening a new Microsoft data centre region in Poland and implementing a skills program to digitally train around 150,000 people in e-learning, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT). Last year, Microsoft announced the launch of its first data centre region in Poland, focusing on digital security.

In 2021, Google announced a major investment in the Polish capital, Warsaw, with plans to establish its biggest cloud technology development centre anywhere in Europe. The US tech giant Intel also announced a significant investment at its site in the northern city of Gdańsk, which is home to the company’s largest research and development (R&D) centre in the EU. Intel has stated that the new facility will be built in an “intelligent” and sustainable way, with gold standard environmental certification and chargers for electric vehicles.

It should come as no surprise to learn that Poland is surpassing competing countries like China, India, and Brazil in various areas of growth, including online services. According to research from HackerRank, Poland also has the third best developers in the world, behind China and Russia.

It would be remiss of me not to point out that Poland has benefited heavily from a European alliance - the country has received billions of euros in grants and loans from the EU for post-Covid recovery, as well as investment and benefits from the EU customs union and single market. In 2024, EU funds are almost 3% of Poland's GDP, and the Polish Minister for Funds and Regional Policy credits the EU with its economic boom, which includes a six-fold increase in Polish exports. Poland’s success is, therefore, more broadly Europe’s success.

But wait. How will Poland power its growing economy? Over 70% of the country's energy consumption comes from fossil fuels, primarily coal, and Poland currently has no operational nuclear power plants for electricity production. Thankfully, the Polish government has a plan. In 2021, it announced that six large reactors would be built by 2040, with plans to implement subsequent units every 2-3 years. The first plant will use AP1000 technology from the US company Westinghouse, and Poland's Ministry of Climate and Environment has secured two South Korean APR1400 reactors for a second nuclear power plant.

Developing a new nuclear program requires collaboration, and the West is stepping up, with Poland securing support from Canada and Polish and Dutch nuclear regulators agreeing to cooperate. Poland's Ministry of Industry and Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry have also signed a memorandum to promote Polish-Japanese cooperation in the nuclear sector.

If these goals sound unachievable, consider that Poland doesn’t have the same problems with excessive red tape that plague other parts of Europe. It offers a beacon of hope as I watch my country (Britain) struggle to rebuild its flailing economy and wrangle with excessive regulatory barriers. Since I don’t live in Poland, I asked the esteemed Polish Energy Analyst Jakub Wiech what he thinks. He told me:

“Nuclear power plants in the European Union take a long time to build. This is a sad reality; the process of constructing these units is prolonged by bureaucracy and a market structure that favors renewable energy sources. Nevertheless, I believe that Poland will efficiently build its nuclear power plants—primarily because the energy situation forces it to do so. Poland desperately needs new, emission-free capacities to replace coal in the 2030s. Moreover, Polish society supports nuclear energy—around 80% of Poles are in favor of this technology. This creates pressure on politicians.

Through the last several years, I have witnessed growing support for nuclear energy in Poland. Today, there is no party in the Polish parliament that is anti-nuclear. Even the Polish Greens do not oppose the construction of nuclear power plants. This shows that Polish society will exert immense pressure on the government to complete the project as quickly as possible.”

In summary, Poland has the political will and ambition, the public support, the necessary skilled workforce, the international collaboration, and the investment needed to make its plans a reality. Poland is the welcome antidote to the disaster that we’ve witnessed in Germany. A note for environmentalists: if you want to see a country wean off its heavy reliance on coal, root for it to go from economic strength to strength, and make sure nuclear is part of the picture.

In some parts of Europe, lessons have been learned since the energy crisis and from mistakes like Energiewende. Europe still has strong hands to play - it just depends on which part of the map you look at.

I wanted to take this opportunity to thank you, not just for your informative posts but for a convention you use in your writing that I rarely see nowadays (actually, I think you're the only person, apart from me, that I've noticed using it): before you use an Abbreviation/Acronym (A/A) you do what I just did, expand it and introduce the A/A in parentheses. I don't know if it's mainly American posts on politics, but I find it really irritating when I have to repeatedly interrupt my reading to look up an A/A, so much so that I've got a easily accessible note with all the ones I've come across that's got about 130 entries so far. I realize that the whole purpose of A/As is to avoid repeatedly writing relatively lengthy phrases, but the key word there is ‘repeatedly’. It's really just common courtesy not to assume that everyone reading knows what your A/As mean. So thank you for having the courtesy of explaining your A/As 😊.

I would argue that with the Sizewell C project Britain as hard as it is to believe is actually somewhat ahead of the US in constructing new nuclear. Remember in the US Vogtle is now finished and at the moment there is no follow on AP1000 project to Vogtle while Britain actually has a strategy to keep building EPR's. In all likelihood the next AP1000s will be built in Poland and other parts of Europe.

Another comment I will make is that in terms of construction time Sizewell B was actually a fairly successful project undertaken long after the US and many other countries had completely stopped building new nuclear. Sizewell B was constructed in roughly 5 years from 1991 to 1996. At that point the last new nuclear power plant in the US had last started construction in 1978. Sizewell B was also the first PWR built in the UK. What makes Sizewell B unsuccessful (and to be clear there is a good chance Sizewell B will operate for 100 years so success is a relative term) is there was basically a 10-year period of lawsuits and paperwork leading up to the plant's groundbreaking. BTW, this is actually a pretty good time frame compared to the fifth and largest air terminal at Heathrow Airport(Terminal 5) which spent almost 25 years in various planning and legal disputes before any construction ever started.

**Interesting video below from the construction period of Sizewell B.

https://youtu.be/FyRRBP1WqpQ?si=bR6emAwpAUyDUeDp&t=29