A new report shows we may be on track to keep below 1.5°C warming

There's a glimmer of hope. So why aren't people celebrating?

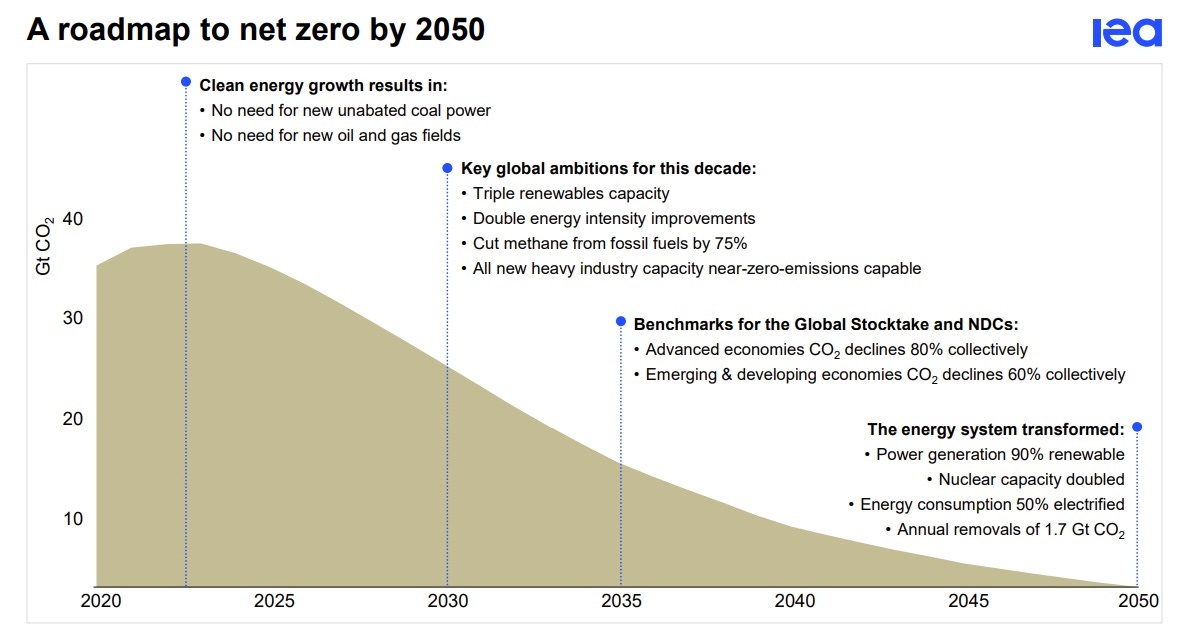

There’s good news – the recently published International Energy Agency (IEA) report Net Zero Roadmap shows that if the current trajectory of green investment, increased clean energy, and switch to electric vehicles (EVs) continues, we can keep below 1.5°C warming.

In May 2021, the IEA published its landmark report Net Zero Emissions by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. The report showed how the global energy sector could contribute to the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the rise in global temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. The updated Net Zero Roadmap is optimistic based on what has been achieved so far.

Why does this matter? Scientists think that warming above 1.5°C could increase the risk of triggering major tipping points, including destroying coral reefs and polar ice sheets, which would add to sea level rise. For many years the focus has been on keeping below 1.5°C, and in recent years it has become a global concern that we are on track to exceed 1.5°C.

What does the report show?

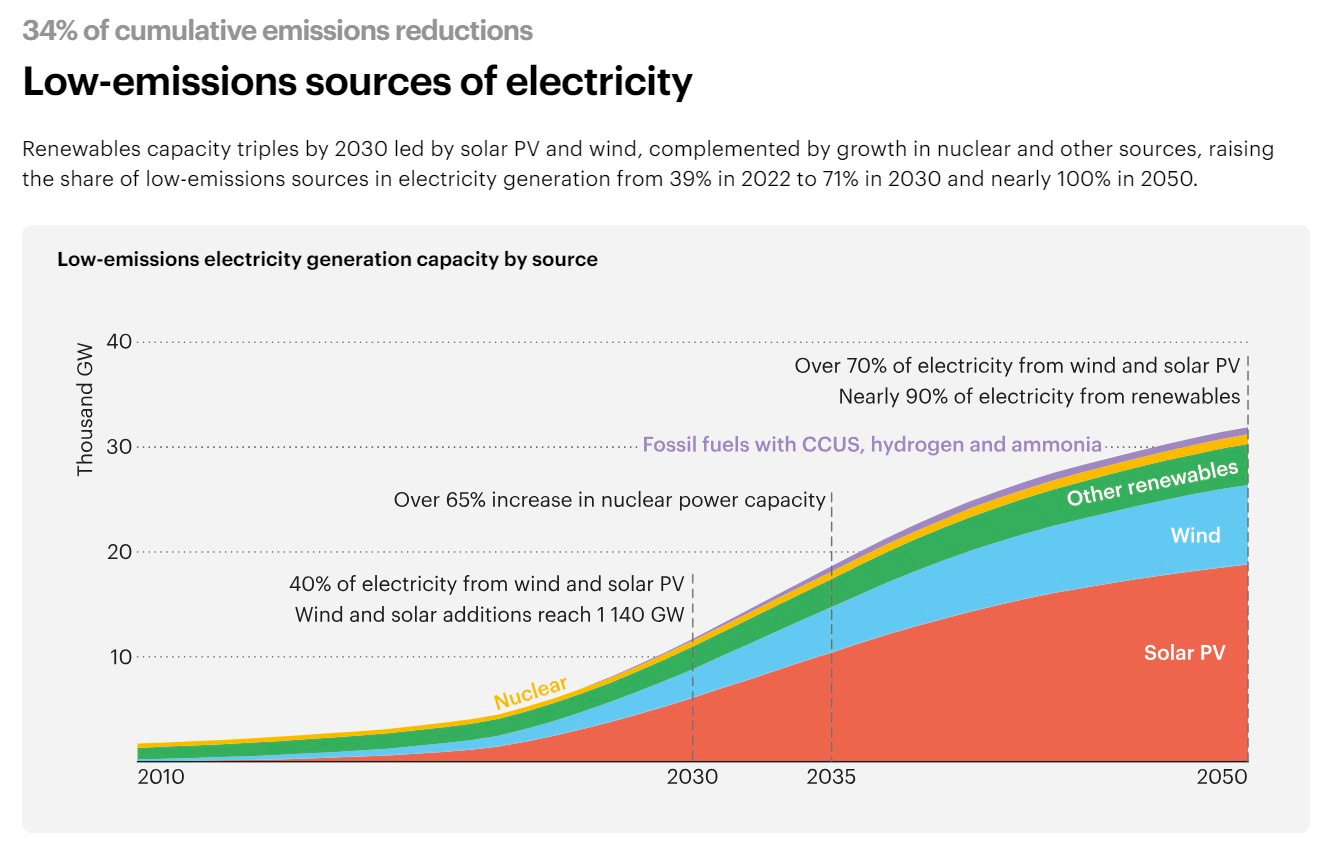

The IEA report looks at how achievable it is to reach net zero by 2050 by including key developments from 2021 and examining future projections. The report concludes that: “Renewables capacity triples by 2030 led by solar PV and wind, complemented by growth in nuclear and other sources, raising the share of low-emissions sources in electricity generation from 39% in 2022 to 71% in 2030 and nearly 100% in 2050.” It suggests a 65% increase in nuclear power by 2030.

The report also outlines the contributing factor of an increase in energy efficiency, which needs to continue so that emissions are sufficiently reduced. Setting and attaining more ambitious net zero targets in wealthier nations is also more likely to help keep warming below 1.5°C.

Some countries are taking energy efficiency further than others: Germany has now made it a legal requirement to save energy, while also admitting that it is “doubtful whether the law would meet EU regulations or be enough for Germany to reach its 2030 climate goal of cutting CO2 emissions by 65% compared to 1990”. Ironically, the German government has neglected to maintain enough clean energy, as they shut down the last of their nuclear reactors earlier this year, which means people are now paying the price for energy scarcity. Poor decision-making is leading to a kind of deindustrialisation in the country.

While the IEA report is good news, it may be flawed in reasoning that we will not need to increase energy usage between now and 2050. Increasing energy efficiency is a good thing to do, but it may not be sufficient for meeting climate targets alone, since it also depends on not needing to use more energy in the future.

We should accept the reality that we are very good at finding new ways to use more energy, and therefore should not place our expectations too heavily on energy reduction. For example, imagine if a life-saving treatment was discovered for treating cancer, but it required vast amounts of energy to run. Would we be able to power such technology under current projections of energy usage? Or would we have to weigh up the benefits of using the new technology versus exceeding 1.5°C? Why can’t we plan for both?

The Jevons Paradox

In economics, the Jevons paradox occurs when technological progress or government policy increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, but the falling cost of use results in an increase of demand great enough that resource use is increased, rather than reduced. We have seen this happen many times across history. In 1865, the English economist William Stanley Jevons observed that technological improvements that increased the efficiency of coal use led to the increased consumption of coal in a wide range of industries. He argued that, contrary to common intuition, technological progress is not the solution to reducing fuel consumption.

Yet policymakers around the world still fail to grasp this simple concept, and journalists and activists continue to push for energy reduction as the way to solve the world’s problems.

What should we aim for?

When efficiency makes something effectively cheaper, we then find more uses for it, and more people gain access to it. This is not a bad thing – it can lead to all kinds of innovation and improved quality of life.

While some might call this wasteful, I would point to the positive uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which require a vast amount of energy to rum. Ever ahead of the curve, Microsoft recognises the need for clean energy to power AI and is looking at meeting those demands using nuclear energy.

There is also the increasing need for technologies like desalination, which can provide access to drinking water for people who would otherwise go without, and has (more good news) become cheaper than tap water. These are examples of high-energy technologies that we are using now and will have an increased need for, yet they are not factored into IEA projections. It is not wasteful to want to improve and save lives. We just need to make sure we can power new technologies with clean energy.

As well, pushing the limits of what we know requires vast amounts of energy. The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, which seeks to understand the fundamental structure of matter. Its temporary shutdown due to the energy crisis is a stark reminder that the world needs abundant clean energy. The argument that we should reduce energy usage is at odds with the reality of scientific progress.

Efficiency should not just be about insulating buildings and electrifying everything. It should also be about considering potential future energy needs and allowing room for progress.

When silence speaks louder than words

Interestingly, there has not been much excitement about the IEA report in the media or from activists. As I told presenter Tom Swarbrick on LBC last week, many of these people cling to the idea that we are doomed, therefore they don’t want to hear – and simply cannot believe – any good news about climate action. A few times, I have been labelled a ‘climate denier’ for outlining positive examples of progress on climate mitigation. I think this comes down to negativity bias, which colours the way people see the world and inclines us toward seeing the bad over the good. But young people need to be able to see the progress that is being made, to be hopeful about the future, and also to understand how we can continue to make progress.

Climate activists have been shouting for years that nothing is being done to bring down global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet this report highlights what is being done, and that it may even be sufficient to keep below 1.5°C. Rather than continuing to argue that nothing is being done, the focus of activists should be on observing results, ensuring that action continues to be taken and that nations decarbonise rapidly and efficiently without harming citizens with the measures they take.

One of the only mainstream articles extolling the virtues of the report did so only to highlight one of its fantasies – that of a world powered by renewables. In this Guardian piece, titled ‘Staggering’ green growth gives hope for 1.5°C, says global energy chief, the writer implies that this green investment is mostly about renewables. There is no mention of nuclear energy in the article, and the Director of the IEA, Fatih Birol, is quoted as praising renewable growth.

In fact, Birol has regularly been vocal about the need for nuclear energy, and clear that it is an asset for decarbonisation. Birol has also said:

“Facts show that, in the absence of nuclear power, it will be much more difficult and costly to reach international climate targets,” and, “Solar and wind are becoming very cheap, but one of the cheapest sources of electricity in the world is the lifetime extension of existing nuclear power plants.” Birol has also criticised EU member states for nuclear phase outs.

As well, the IEA published a report in 2022 which outlines that “building sustainable and clean energy systems will be harder, riskier and more expensive without nuclear”, and addresses some of the ways to overcome the challenges of new builds.

An article in Reuters also covers the report without mentioning the crucial role that nuclear energy will play.

Besides that?

Activist reactions to the report also focus heavily on the renewables aspect and ignore the role of nuclear energy altogether, when nuclear arguably faces more challenges in being built and needs some weight thrown behind it to ensure that power plants get built. If we want to see it doubled, we are going to need to talk about how to make sure that happens.

Questioning the narrative

This raises three lines of inquiry for the journalistic world and activists.

One, why is the report being so misrepresented? Should journalists report on these topics as though they are activists? Why aren’t journalists mentioning the nuclear aspect? Has ideology seeped so far into the mainstream media that editors will no longer call out biases that border on misinformation?

Two, why aren’t people celebrating the news that we may keep within 1.5°C warming? When we thought the opposite was true, it consumed the media for months. Why aren’t activists praising the rapid turnaround that might keep the Earth within liveable limits? And how is nuclear capacity going to double when activists keep protesting it?

Three, why is no one questioning the ongoing argument for energy reduction? Why is there so little narrative in favour of using more energy, not less? Why has virtually everyone bought into the idea of energy scarcity, when our lives are so dependent on producing vast amounts of energy? Why is the focus on energy reduction instead of on clean energy abundance?

Cause to celebrate

Personally, I am glad to see the clean energy increases and other measures that are helping to reduce emissions worldwide, but let’s not pretend that renewables (for want of a better term) alone will get us out of this mess. We need to heavily increase nuclear energy capacity as well.

If we want to solve the world’s problems effectively, using science and not wishful thinking, we need journalists to step up and report information accurately and to ask relevant questions, rather than cherry-picking information to suit an agenda. As for activists who don’t seem to want to celebrate the good news that it may not be the end of the world, perhaps we should question why they are so wedded to doom-laden scenarios, and why the media has allowed their views to become so dominant that when good news that doesn’t fit the narrative arises, it is barely covered at all.

The same rules, regulations, lawsuits, and activism that has been brought against nuclear power and fossil fuels is now making it harder to build and deploy wind and solar. That factor alone makes these forecasts doubtful. The chart showing solar dominating fails to acknowledge the intrinsic limitations of "ground-based" solar and the need for backup sources.

I'm hoping the current campaign to prevent the renewal of the NRC's chief succeeds. Without someone less anti-nuclear in that position, it's going to be hard to make progress.