“It is change, continuing change, inevitable change, that is the dominant factor in society today. No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be… This, in turn, means that our statesmen, our businessmen, our everyman must take on a science fictional way of thinking.” – Isaac Asimov

I’m a huge fan of the late science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. In the Foundation series of books, Asimov is concerned with the stagnation and degradation of society once a certain level of comfort and wealth has been achieved. One of the main characters, mathematician Hari Seldon, tries to develop a way to predict future downfalls of humankind to address them before they take place, through a method he calls ‘psychohistory’, which is a mathematics of sociology that he develops in the books.

The most unusual thing about the Foundation novels, and Asimov’s works in general, is the timescales he works with. We are not talking about looking a few decades into the future, but tens of thousands of years ahead. Seldon is eventually able to predict the imminent fall of the Galactic Empire, and is also able to predict actions that may prevent a Dark Age from lasting 30,000 years before a Second Empire arises from taking place. He puts wheels in motion to prevent these things from occurring, or, where they seem inevitable, to ensure that there is a push to rebuild afterwards.

Asimov’s long-term thinking throws into sharp relief just how short-term our approach is today. Politicians don’t tend to think beyond the end of their term of office, let alone decades into the future. People generally tend not to think of the future past their children or grandchildren. This lack of foresight is short-sighted. I believe we are currently experiencing a similar dilemma in the West to what Asimov describes – although our society is not as advanced as in the Foundation novels, we have become so comfortable with our achievements that we have become complacent about maintaining them or progressing further. As evidenced by the constant criticism of ‘how long’ it takes to build nuclear power plants (the average build time is 7.5 years), even though they can provide electricity for the entire human lifespan, we have become bad at building for the future, and therefore also cannot plan for future generations.

There is no argument for our complacency that is better represented than the current social movement against producing energy, which perhaps began with Boomers, but is now being led mostly by Gen Z, also known as ‘the sustainability generation’, and also to some degree by Millennials. The irony is that these generations have been the most comfortable of all (and –full disclosure – I am a Millennial); unlike my parents who grew up in poverty in India, and were then manual labourers in Britain, we have had it easy. We haven’t suffered through truly gruelling labour, we don’t need to know how electricity grids work, and most of us have never stepped foot in a mine or experienced electricity blackouts. The divide between what it takes to maintain a high quality of life and the understanding of this has also widened over generations; there are several reasons for the fall in manufacturing in recent years and Gen Z wanting a better work-life balance is part of it, plus the advent of new technologies that have led to a natural restructuring of the workforce.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Thanks to years of development and growth, we live in a time of prosperity, facing fewer core challenges than past generations. Need to read after dark? Flick a switch and you have light. Want to go for a walk? Great, the streets are lit too. Feeling sick? You can see a qualified medical professional. And so on.

The problem is that thanks to all of this, a disconnection has occurred between our lifestyles and what it has taken to get us here. The lack of understanding of the skilled labour, need for industries, and mining for raw materials that enabled these lifestyles, and the fact that the toll those things took on the environment was inevitable, but not permanent, has repercussions for society. I was once part of the problem, fighting to forge a society that would be independent of fossil fuels, without thinking about our continued and growing need for reliable electricity and fighting for the alternatives. My argument was the standard traditional environmentalist argument: that we need to live with less. I was wrong.

Now, the argument has gone so far that activists argue that we should just stop oil overnight. But can it be done without causing immense harm to people?

Can we even just stop oil?

For most of human history, we lived in poverty, and billions of people in the world still do. It is possible to hold two ideas in our heads simultaneously: one, burning a lot of fossil fuels enabled us to escape poverty and attain the high quality of life that we enjoy today, with access to healthcare, medication, clean water, food and shelter, and low infant mortality rates; two, burning a lot of fossil fuels also had an environmental impact, which now needs addressing.

The good news is that we know how to tackle this issue already, as I explained in my last article. But is it as simple to make other rapid changes as activists believe? We know how to lower emissions and tackle air pollution, but what about oil?

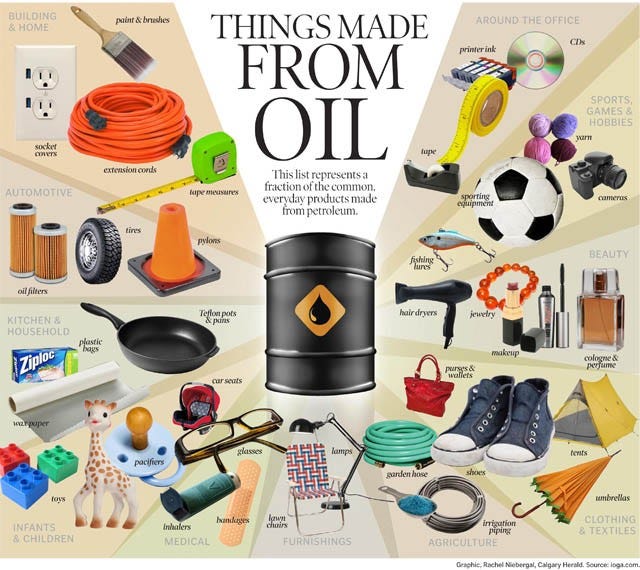

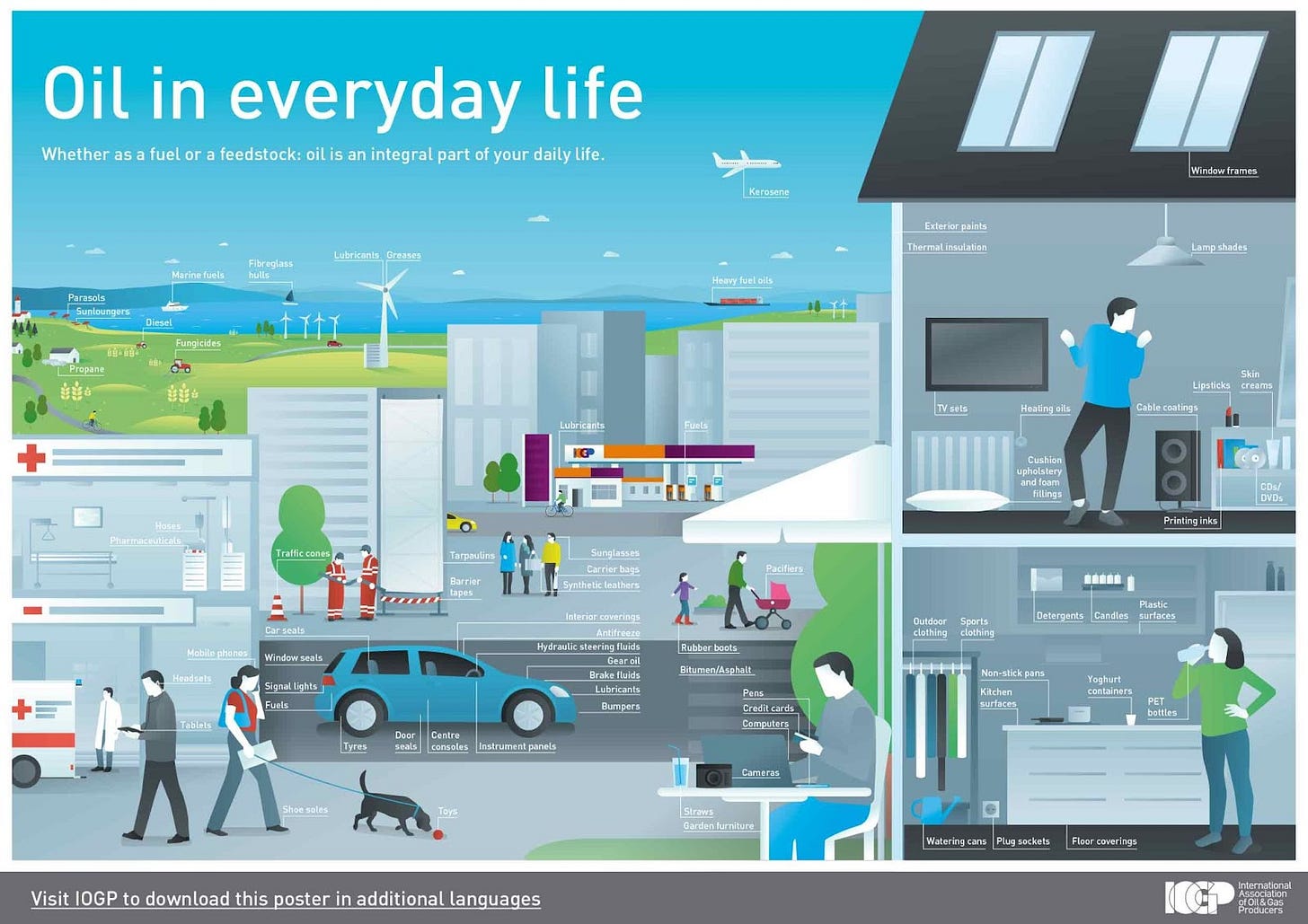

The fact is that we live in a highly oil-dependent society.

About 45% of a typical barrel of crude oil is refined into gasoline, and an additional 29% is refined into diesel fuel. The remaining 26% is used to make plastics and other products. There is good news in these figures, as it means that we can reduce a lot of our dependence on oil by making the switch from petrol and diesel cars to electric vehicles, which is a trend that is taking place in many countries already.

This is an incremental change that will take time, which is the opposite of just stopping oil overnight. The reality is that people would be harmed by taking such drastic measures. As we learned from the energy crisis last winter, energy scarcity is dangerous and claims lives.

What about the remaining uses of oil, then?

The bad news is that oil is very difficult to replace.

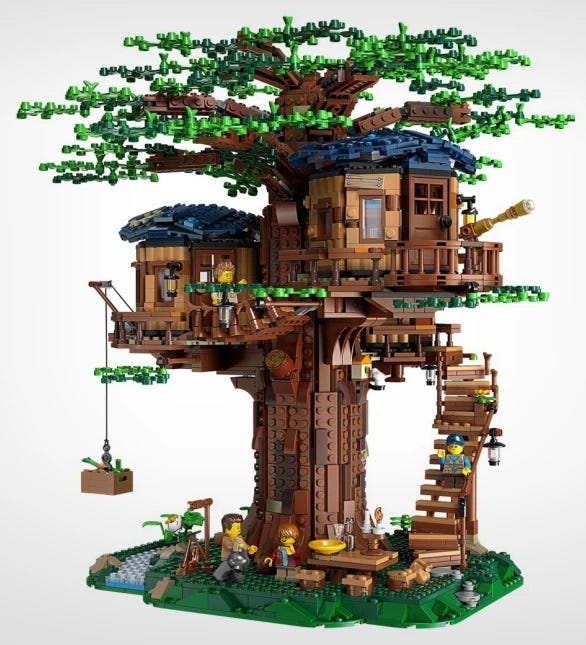

Many well-meaning companies have been trying to go oil-free, such as the Danish company Lego, which manufactures plastic construction toys. Over many years, Lego has spent millions trying to find a way to switch to making its trademark colourful bricks from recycled plastic bottles made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) instead of plastic. Unfortunately, it turns out that the non-oil-based alternative material demands extra ingredients for durability and greater energy for processing and drying, which makes it more carbon-intensive. Tim Brooks, Lego’s Head of Sustainability, summarised: “It’s like trying to make a bike out of wood rather than steel… In order to scale production [of recycled PET], the level of disruption to the manufacturing environment was such that we needed to change everything in our factories. After all that, the carbon footprint would have been higher. It was disappointing.”

Instead of going ahead anyway and virtue signalling that they are now plastic-free, Lego has ditched plans to switch to PET, since doing so would have had a greater impact on the environment.

Of course, many anti-oil activists would argue that Lego should stop making the bricks altogether. They would argue that they are unnecessary and wasteful. But I disagree. I recall many years of constructing large and complicated architectural designs with my brother when we were children; he was fascinated by the way things work and are put together, and he later trained to become an engineer (a field he now holds a senior position in). This link between playing with Lego and developing engineering skills has been well-documented elsewhere. The irony of wanting to just stop oil is well represented in the idea that we don’t ‘need’ Lego. We don’t ‘need’ to build housing, railways, or power plants either – if we are happy for society to stagnate and for future generations to suffer.

Let’s ignore the idea of an immediate transition, then, and consider what can be done to stop oil eventually.

What are the alternatives to oil?

There is no way out without technology.

There are many technological solutions to global problems that we can employ today, but in this area change tends to be slow. Politicians are reluctant to invest heavily in large-scale projects or to commit to long-term endeavours, while many traditional environmentalists reject what they see as ‘techno-fixes’ since they also argue that it’s the fault of technology that got us here (and I agree with this statement in a way: without technology, I wouldn’t be here, and it’s likely that you wouldn’t either).

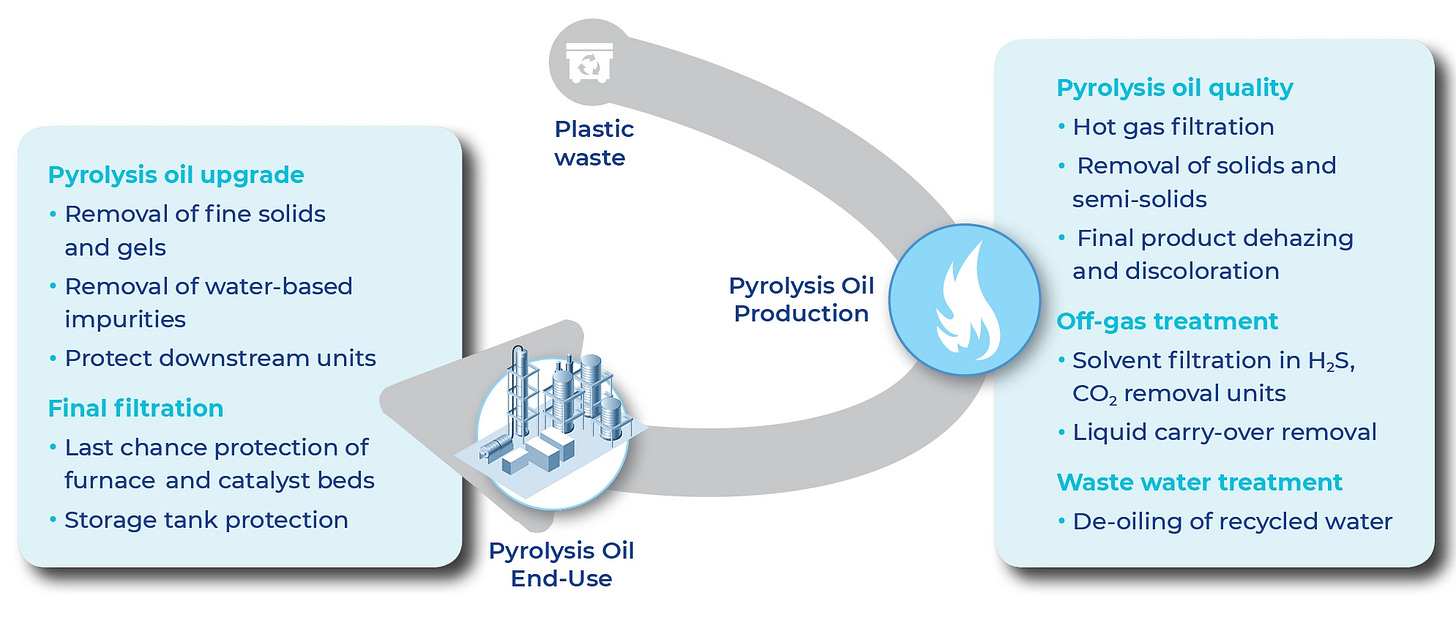

The best option we have for replacing oil involves pyrolysis. Pyrolysis is the heating of an organic material, such as biomass, in the absence of oxygen. Pyrolysis oil, sometimes also known as bio-crude or bio-oil, is a synthetic fuel that can substitute petroleum. It is obtained by heating dried biomass without oxygen in a reactor at a temperature of about 500°C (900°F) with subsequent cooling.

If pyrolysis can replace diesel, why didn’t you already know about it? Because it is expensive – partly because of the parts required to construct reactors, and partly because it requires a lot of electricity to run.

This brings me back to a point I’ve been making for years: we should be aiming for energy abundance.

As we shift towards electrifying everything, switching from gas boilers to heat pumps, and diesel cars to electric vehicles, much of our demand for oil will be replaced naturally. But the alternatives will require more electricity, and unless the electricity grid is supplying us with clean power, we have a problem. Replacing oil through pyrolysis is part of the solution, but it will also require more energy.

Ultimately, activist wishful thinking aside, developing countries are going to continue to chase economic growth to increase incomes and improve their quality of life regardless of environmental impacts. Access to electricity is integral to this. Using oil is not up for debate. Pushing the transition in a positive, solution-driven direction is the only thing that makes sense.

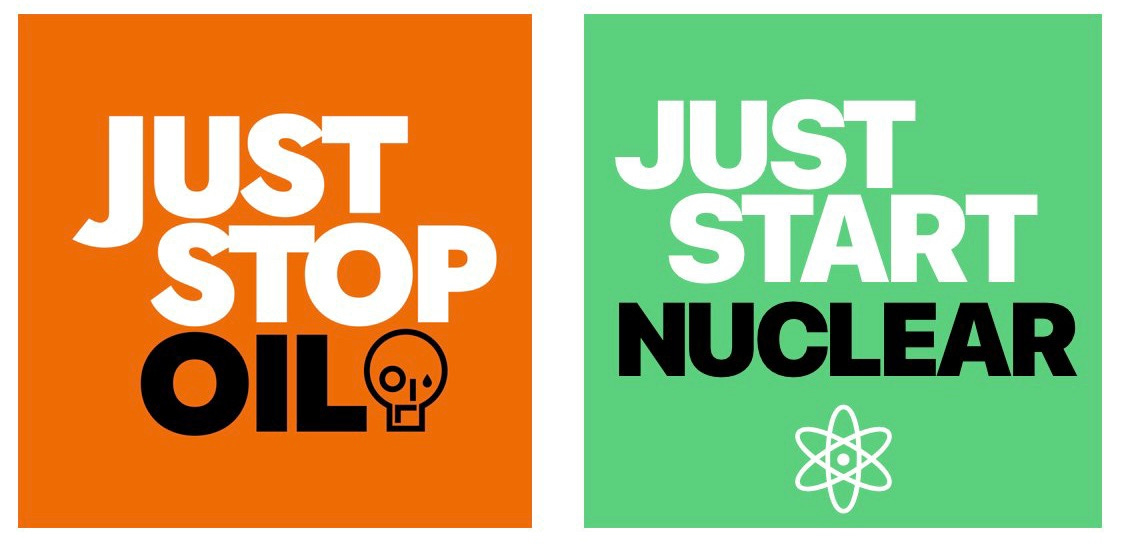

Social movements often succeed when they choose to fight against something instead of in favour of something. But I think environmental groups got this approach wrong when it came to tackling climate change. As someone who used to protest fossil fuels, I think we missed a trick in not fighting for what we need to replace them as well. Through a combination of misinformation and pop culture references, we even protested one of the key solutions to saving the planet – nuclear energy.

As I’ve explained before, we can build all the wind and solar power people want, but we will still need baseload power to back them up, and historically this has always either come from fossil fuels or nuclear energy. Although the upfront costs for the alternatives appear to be cheaper than for nuclear, this is incorrect when the figures are viewed in context. As well, we need to be aware of shift-loading the costs of wind and solar power onto ordinary working people. I’ve also seen NGOs arguing for building wind and solar in less wealthy countries, and I find this tactic appalling. Intermittent energy is not what we in the wealthy West used to escape poverty. We burned a lot of fossil fuels to develop. We don’t get to deny other countries of that now.

Zooming out

Everyone I know seems to agree: the world has gone to pot, and there’s no coming back from it.

I can understand why. For a while, I stopped opening my social media apps because the news has been continuously bleak. The details are depressing and horribly graphic. It is a double-edged sword: we have more easy access to information than ever before, but that means the bad news reaches us in detail as we sit down to dinner with our families, and it feels all-encompassing.

We are back to the problem of narrow thinking. As well as looking at the details of specific incidents, we also need to be able to zoom out to see the bigger picture. We need some balance. We need to think like Asimov. By doing so, we can see that over a longer timeline, we are still doing extraordinarily well. Better than we have ever been, on almost every metric.

Overall, war deaths have been declining since 1946 - in some years in the early post-war era, roughly half a million people died through direct violence in wars. In recent years, the annual death toll has been less than 100,000. The past thirty years have also seen immense progress in improving the quality of life for much of humanity. Extreme poverty has fallen by nearly two-thirds, from 1.9 billion to around 650 million. Life expectancy has risen in most of the world, as have literacy levels and access to education. Infant mortality has fallen. Despite perceptions to the contrary, the average person born today is likely to have access to more opportunities and have a better quality of life than at any other point in human history.

Let’s take a moment to applaud how far humankind has come. Our lives are filled with miracles of science and technology thanks to the last 300 years of the scientific method. Western civilization has mostly overcome superstitious thinking, barbarism, and totalitarianism. We have fought for democracy, against slavery, towards equality, and we have achieved many of these aims the world over. Humanity is, in many ways, thriving. The Earth isn’t doing too badly either – yes we need to tackle air pollution, but we also saved the Ozone Layer and there is a lot of other good news too. Before you send pitchforks my way, read the data for yourself.

But we have lost our way in terms of maintaining what we have and pushing for more. A society that understands the need for progress and energy would never enter into an energy crisis. We have forgotten what fuels us and how integral industrialisation has been to our lifestyles today. We have lost sight of the bigger picture.

How do we fix it?

We need to follow science, not slogans.

The solutions are in many ways very simple. We have the knowledge and wealth to be able to build what we need to tackle the problems we face. We may lack the skills due to a shifting workforce, but this can be remedied through offering funded training opportunities, recruitment drives to attract workers, and essentially the promise of good wages afterwards. Change does not happen overnight, but it can occur rapidly through incremental changes and forward-thinking.

It’s good that more of us are comfortable rather than struggling, but we need to start thinking ahead to maintain some balance. We need to stop being complacent. When we stop aspiring for progress, we lose sight of who we are. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain had less than 2% of the world’s population, but was responsible for half of all global cotton textile production, and over 65% of all coal mining. Now, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution struggles to build high-speed rail, housing, and power plants. To get out of this rut, we need to think like Asimov.

When I first diverged from traditional environmentalism to call out unscientific approaches and to advocate for solutions instead, not a day went by where I wasn’t accused of being a ‘shill’. I don’t work for the industry and never have done. I earned my stripes in the environmental movement, and believe that environmentalism can still offer much to the world, so long as it is logical instead of just waxing lyrical.

The truth is that I am a shill. I am a shill for the human race. I want to see the end of needless suffering and death from preventable diseases. I want to see all poverty eradicated. Apart from a few specific war-mongers, who doesn’t want to see the end of all war? I want all life on this planet to thrive. I want to see the best of humankind during my brief presence on this pale blue dot that we are so fortunate enough to inhabit. I want us to live long and prosper.

Humans are capable of solving immense problems and achieving great things, through forging strong values and working together. I am a shill for progress because I want to see what we do next, once the immediate – and entirely solvable – problems like air pollution, poverty, and climate change have been solved.

Just as psychohistory enables Hari Seldon to predict the decline of civilisation, it is also able to take steps towards its preservation. We can too. If we truly want to just stop oil, we need to just stop dithering, and just start building. For humankind to flourish, we’re going to need a lot more energy to achieve our aims. We need to just start nuclear.

Then let’s see what we can achieve next.

Eminently sensible article. Stopping oil is nonsense given how essential it is to a host of irreplaceable products and services our civilization. The science and practice of modern medicine along would be utterly impossible without a host of petrochemical products. Modern agriculture is utterly impossible to produce food on the scale done by our civilization and upon which the lives of billions depend.

But it's quite right that we can usefully reduce dependency on oil and gas by increasing use of electricity generated from nuclear power. There are always complaints about how long a nuclear plant takes to build, and unpleasant whining that this length prevents it from being a solution. This is a phony argument. Canada's first nuclear power demonstration reactor, NPD-2, was built in less than two years. I know; one of my best friends (now deceased two years ago) was one of the draftsmen designers for the plant. The delays preventing nuclear power plant construction are entirely artificial and of purely human origin.

Second, a nuclear power plant is forever. When modern society builds power stations now, there is no expectation of ever shutting them off and walking away. The Sir Adam Beck 2 hydraulic station in Niagara Falls will operate forever. Ontario is now refurbishing ALL its nuclear power plants for operation for more than 60 years of productive life. At that time in the future, there will be another decision made to renovate them again. As long as modern civilization exists, it will need reliable electric power. And that means nuclear.

It’s always so good to read your posts.

We all want the same things, cleaner energy, less poverty, more progress for all.

A small minority are playing a game to hold the success and successful back simply because they want what is delivered but don’t want to be the ones to deliver because it’s too hard for them to deal with their own cognitive dissonance or outdated political stand.

Fortunately as in the past, they will only get away with it for so long, knowing it was such a shame they held nuclear back and prevented the carbon emission reductions that could have helped us all.

Ni time to delay, let’s build away!

We are the first sustainable generation, just look at the damage from before, Hanna Ritchie explains that so well in here:

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7LAWY49zl6KwI2DlVmazCe?si=GdwUmtSERlmqiHy6fUiQJw