Can we prevent this virus from infecting people?

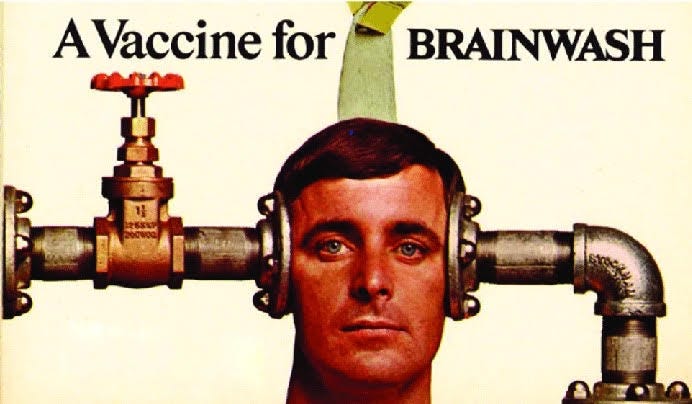

The trick to developing immunity to misinformation

“The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.” ― Isaac Asimov, 1988

There are many variations of this meme, which shows two people pointing at a number on the ground. From either person’s perspective, the number is either a six or a nine. This image has been used widely to illustrate that people can hold opposing perspectives and both of them can be right, which implies that truth is subjective. While this may be a fair assertion when debating, say, who your favourite Star Trek character is (Mr Spock, of course), it simply isn’t true when discussing universal scientific truths. For example, the Earth is not flat; it rotates around the Sun; humans evolved from ape-like ancestors, and so on.

Perhaps in this specific example we cannot ascertain with certainty what the number in the meme is, but that doesn’t mean that there is no objective truth. Someone intentionally drew a six or a nine in the room, and there should be some indicator of which direction the number was painted in, perhaps relative to the way it is facing or the surroundings it is in. Given enough context, there is likely an answer to the question of whether it is a number six or a number nine.

You’re probably thinking “it’s just a meme”, but it is illustrative of a wider problem where information is presented in this manner: as if the truth is subjective. I only need to open any social media app to see that ‘subjective truth’ seems to be everywhere, and every day there is new questionable information to think about (this assertion isn’t only anecdotal, but is also supported by research).

I thought I’d seen it all when I started out debunking myths about nuclear energy, after having believed misinformation about the technology for many years, which was not only very convincing but widely repeated and rarely countered. But the world moves fast and now misinformation that is being propelled by war has upped the stakes even further.

Social media has now become a popular way to consume news media. Online sources are the second most used platforms for news after broadcast television, used by over two-thirds (68%) of UK adults. Just under half (47%) of UK adults use social media for news, and young adults aged 16-24 are much more likely to consume news online than adults generally (83% vs 68%). Social media platforms dominate the top five most popular news sources among 16-24s, with Instagram at the top of the list.

This might matter less if there was high-quality journalism on social media sites, but instead, there is a lot of misinformation. Instagram in particular is guilty of this, as it is shaping people’s world views about (for example) vaccinations and new technologies based on false narratives. As well, this false information is often promoted by algorithms on social media, which means that fake news gets shared widely and drowns out more sensible reporting.

Why should we care about misinformation?

Misinformation is the sharing of false information, some of which is highly impactful and has real-world implications. It can lead to poor judgement and decision-making, and even bad policymaking. It also impacts a person’s reasoning even after it has been corrected, which is known as the continued influence effect. Misinformation has been identified as a contributor to various contentious events, including elections and referendums.

Has it gotten worse? Yes and no. As social psychologist Dr. Sander van der Linden points out in his book Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity, misinformation is not new. Previous large-scale examples of misinformation taking hold in populations include Nazi propaganda, which heavily relied on the printed press, radio and cinema, and misinformation campaigns that have been traced back to Roman times when emperors used messages on coins as a form of mass communication to gain power.

However, due to the rise of the internet and the widespread use of social media, misinformation can now spread globally and more rapidly than before, and many people fall for it. Thanks to echo chambers, exposure to information that can challenge a person’s perspective or foster a wider debate has also become more limited. This has led to many negative outcomes including misleading information around COVID-19, the Australian Bushfire, people burning down 5G masts in the UK because of conspiracy theories, and people dying after ingesting methanol because they were convinced by social media that it was a cure for coronavirus. It is a pressing, worrying problem. To tackle it, we first need to understand why we fall for misinformation.

To err is human

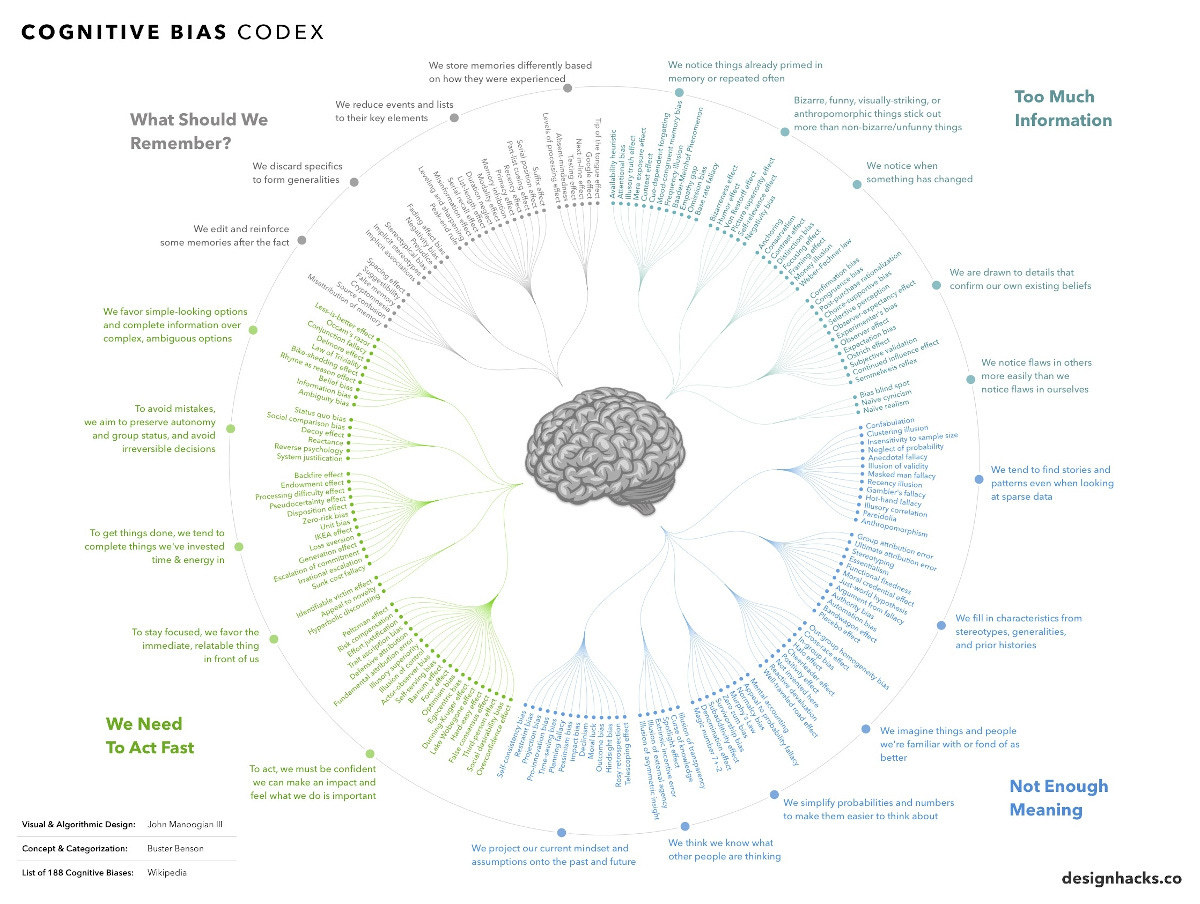

It’s unpleasant to think about, but there are 188 cognitive biases in existence and we are all at their mercy. Cognitive biases are lenses that we see the world through, which are influenced by myriad factors including our experiences, emotions or ‘gut feelings’, existing beliefs, moral values, and whether or not we trust the source of the information. Some of these biases have served humankind well for a long time, for example, using shortcuts - in many cases, it’s easy to take shortcuts instead of engaging in critical reasoning about every topic we come across, which would make everyday tasks overwhelming and tedious. Just as we may undertake certain actions ‘on autopilot’, like walking a familiar route to work or school, our minds also fall back on existing feelings and ideas when we take in new information, to reduce the mental labour of working out whether or not the information is relevant to us, or important, or something we need to act on. The problem is that many of these views, without adequate assessment, serve to confirm our existing beliefs, which leads us to believe things that are not true.

Some examples of cognitive bias include:

Confirmation bias: the tendency to seek out and believe information that supports our existing beliefs and expectations. (As Mr Spock puts it, “In critical moments, men sometimes see exactly what they wish to see”.)

Anchoring bias: the tendency to rely too heavily on one piece of information when making decisions. This is also usually the first piece of information acquired on that subject.

Availability bias: the tendency to believe the things that are easiest to remember. Hence clickbait and sensational stories, which have simplified messages, spread rapidly.

Familiarity bias: the tendency to believe that something is true because we have heard it so often. This can be true of stereotypes in pop culture and is easily fostered by social media where repetitive exposure can lead to increased believability.

Repetition tends to increase the persuasiveness of misinformation. So if you keep repeating a falsehood, it creates associations in the brain, and the mind infers that this object has a higher value concerning the question being considered. In psychology, this phenomenon is known as fluency for truth.

Many vested interests and those who believe misinformation themselves use these biases to their advantage. If this was a war, I would argue that the other side is winning. Thanks to some of these people being convincing communicators, and using storytelling that plays on these biases to their advantage, they have been able to influence what wider populations believe on multitudinous topics ranging from gene-editing to nuclear energy to degrowth as a solution to climate change (it’s not).

Another thing that works for misleading storytellers is fear-mongering. As van der Linden explains in an interview with Nature, “We know that emotional content is more likely to go viral on social media, especially negative emotional content. And so one strategy that a lot of misinformation producers use is to appeal to anxiety and fear in the crafting of their messages, because that's what gets people going. That's what gets shared. That's what's exciting. You know, boring fact-checks don't go viral. They don't have sensationalist headlines. They don't have emotive words. But then as we talk about in some of our interventions, you can't be too ridiculous.”

Since activists who spread misinformation tend to use the same tactics, I can pick two seemingly vastly different topics that I have worked on myth-busting over the years and draw many parallels between them. One is in the area of energy, and the other is in the area of medicine.

With both childhood vaccinations and nuclear energy, activists have over many years been able to convince many people, including politicians and world leaders, that these technologies are dangerous and unnecessary. They have argued that nefarious ‘vested interests’ (i.e. Big Pharma and the nuclear industry) have only developed the technologies because they value money above the health of ordinary people. Activists have labelled these technological advances as ‘unsafe’, with accidents blown out of proportion and used to tarnish the technologies altogether (for example, the conspiracy theories around the childhood MMR vaccination spread rapidly to all childhood vaccinations). The alternatives - for example, the impacts of fossil fuels and measles, mumps and rubella on human health (particularly child health), have been altogether ignored in their arguments. Without this context, which requires a deeper dive into the subject than most people will undertake, the fear-mongering aspect of the stories has led to real-life consequences. The world remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, and outbreaks of preventable diseases now occur in wealthy countries. We know that people die as a consequence of the former - when nuclear power plants are shut down. Occasionally, there are outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles in countries where vaccines are easily accessible, and children sometimes die because they weren’t vaccinated.

In Foolproof, van der Linden explains that whereas “lies and fake news tend to be simple and sticky, science is often presented as nuanced and complex.”

Framing is also important. Activists continue to stoke fears of radiation and supposedly dangerous chemicals while ignoring the actual more frightening alternatives of health impacts from air pollution and climate change and dying from preventable diseases. By framing the topics this way, telling outright lies about safety and health risks, and repeating these scary, sticky ideas over decades, they have managed to persuade millions of people to fear these technologies. The same can be said of GMOs, although I think I’ve made my point sufficiently with the two examples I’ve used.

The greatest irony is that anti-nuclear activists have also been able to convincingly embed their unscientific position within environmentalism, even though nuclear energy is the cleanest and most environmentally friendly energy source available to humankind, with the smallest land footprint of all energy sources.

Slogans and stories are sticky, but they may not be true or helpful. Hence I’ve argued before that catchphrases and slogans used by activists are often convincing and successful, even when they are inaccurate. Stories, however, are essential to communicating scientific matters, and we need more people to tell them.

After all, it’s much easier and faster to respond with “what about the waste?” when I mention nuclear energy, than for me to explain why spent fuel isn’t the problem many people think it is, which takes time and isn’t as catchy or simple as the aphorism “what about the waste?” (I have covered the waste argument in detail in this article.) In my work tackling misinformation, I have honed some of these detailed responses to convey them through catchphrases that have also been popularised, such as “it’s only waste if you waste it” (in reference to being able to recycle spent fuel) and “meanwhile fossil fuel waste is being stored in the Earth’s atmosphere”, which is both true and a sticky idea.

When I first started popularising some of these phrases, I was countered by a few scientists who felt that they were misleading because they didn’t tell the whole story. They told me that it would be better to share scientific papers than to boil arguments down to sticky slogans. But I disagree. So long as the phrase represents the truth, it is necessary and needed to counter the untrue narratives. The slogans are designed to challenge existing perspectives and to encourage people to dive deeper into the topics - although even then, most people are more likely to read an article on the subject than to read a scientific paper. Although no one has studied it directly, I feel sure that coining and popularising terms like “nuclear saves lives”, “energy is life”, “nuclear energy is clean energy”, and “rethink nuclear” has helped to combat the misinformation we’ve heard about nuclear energy for so long. (For a longer read on this topic, I have written about how we used similar messaging tactics in Extinction Rebellion, which were adopted globally and influenced policymakers significantly.)

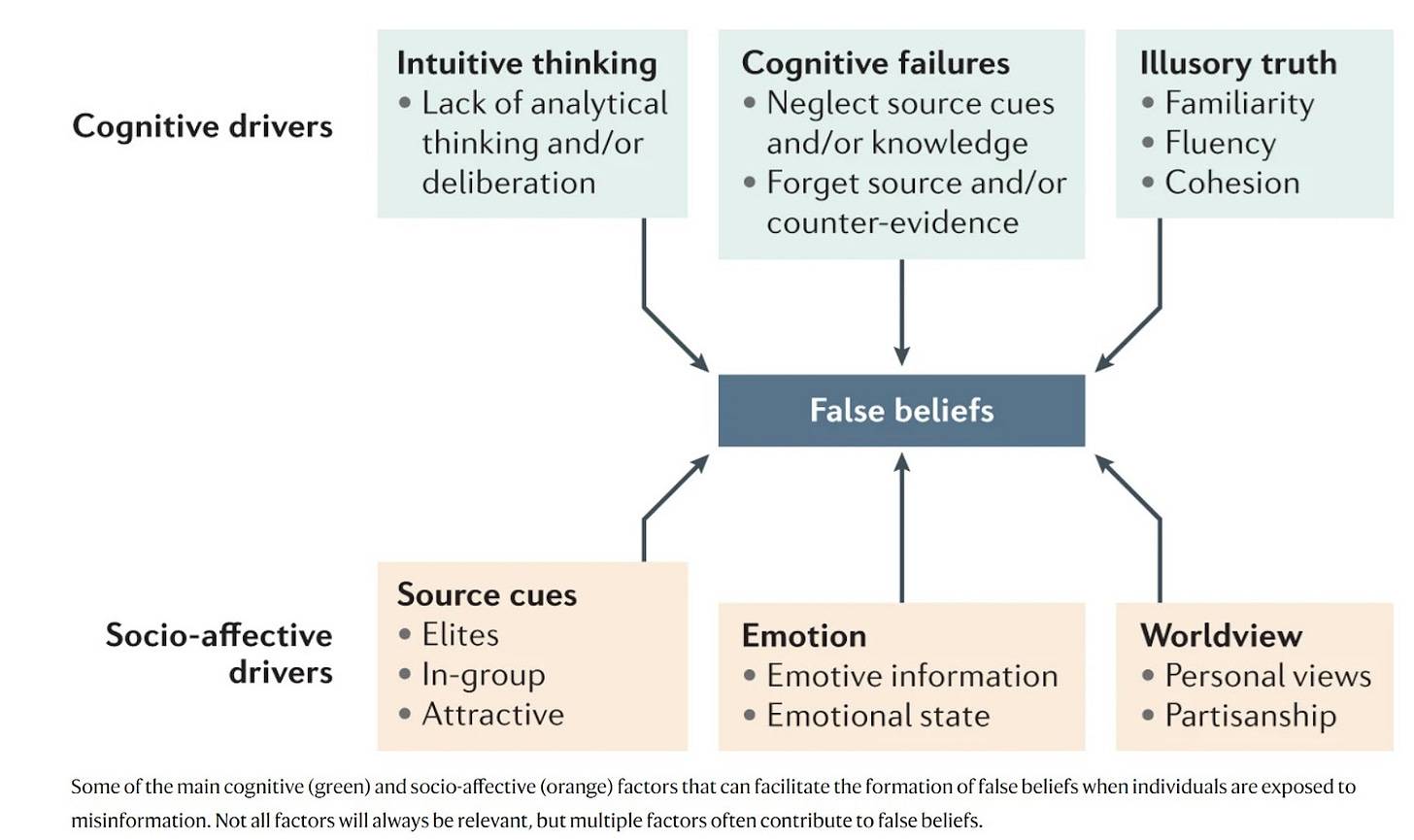

The opposition to my approach of simplifying the messaging - often from people who are frustrated about being unable to tackle misinformation effectively themselves - demonstrates an old model of thinking regarding disseminating scientific information. For a long time, people attempted to correct misinformation by relying on the information deficit model - a term we use in science communication to describe the approach of addressing a lack of understanding with facts. In reality, facts rarely change minds. There are simply too many varying cognitive, social and affective drivers of attitude formation and truth judgements at play when forming beliefs. As well, many people have low science literacy. This doesn’t mean that they are incapable of understanding the information you want to share with them, but that they have their own priorities and may not want to read a scientific paper on a topic that they feel is not particularly relevant to them.

So what can be done about misinformation? Social media is here to stay, and is rapidly becoming a primary news source for Gen Z. Is it possible for humans to become smarter so that we can spot fake news and avoid falling for conspiracy theories?

Cultivating mental immunity

There is solid foundational knowledge of how people decide what is true and false, how they form belief systems, assess new information, and so on. Although there is less research into understanding the psychology of misinformation, and the field is in its early stages, there is a lot of valuable information that can be put into practice now.

The idea of a cognitive vaccine against propaganda was first proposed by psychologist William J. McGuire in the early 1960s. McGuire hypothesised that people could learn to spot propaganda if they were warned about it beforehand through a technique known as ‘prebunking’. With a few caveats, this concept largely holds up when tested; people are less susceptible to misinformation when they have been warned about it. Contrast this with previous attempts to tackle misinformation (the deficit model), and we can see how much work has been done in this field in recent years.

Prebunking is therefore quite a revolutionary idea, which relies on pre-emptive intervention, but it is also essential when you consider the impacts of technology panics, which range from everything from microwaves to lighting and radiation.

In the simplest terms, prebunking involves presenting factually correct information and a pre-emptive correction or a generic misinformation warning before the person encounters the misinformation. This requires thinking about what people’s objections might be to the new information, which isn’t difficult if we look at the general messaging used by activists against various technologies, but is essential if we want to dilute the power of their messaging.

A more sophisticated form of prebunking involves inoculation theory, which is a framework for pre-emptive interventions. The basic idea is that ‘inoculating’ people with a weakened form of persuasion can build immunity against persuasive arguments by engaging people’s critical-thinking skills. This technique of inoculation has been shown to increase the accurate detection of misinformation. Understanding how misleading persuasive techniques are used enables a person to develop the cognitive tools needed to ward off future misinformation attacks, as research has also found that this type of inoculation on one topic can help people spot misinformation in other areas as well.

Debunking can also be effective as a form of reactive intervention, but it is more complicated, since it’s easy to slip into the deficit model, and communicator trust - i.e. who the message is coming from - also plays a role. As I often point out, simply throwing facts at people does not change their minds.

In sum, prebunking and debunking can be effective, but they are still influenced by a range of factors, with mixed results regarding their efficacy. They have to be tailored to the issue at hand, and there is limited data available on how best to employ them, so at this point, the application of the theory is still a process of trial and error. However, if people had been able to employ prebunking techniques before the false information about the MMR vaccine was spread and before nuclear meltdowns were blown out of proportion by the media, we would likely not have seen so many nuclear power plants shut down out of fear and outbreaks of measles in wealthy countries in recent years.

Inoculation in action with gamification

An interesting project that van der Linden has worked on is the game Bad News, which takes the abstract concepts we have discussed here and demonstrates them through gamification.

Bad News enables players to produce and amplify fake news. The video begins with a warning that the viewer might be subjected to attempts to manipulate their opinion (prebunking), and it covers ‘six degrees of manipulation’, which are techniques that van der Linden’s group has identified as marks of misinformation. Play the game yourself and see whether you can spot what they are.

Researchers measured how well players could spot fake news before and after playing the game, and in a dataset of 15,000 trials, they found that “everyone improved their ability to spot misinformation after playing the game”. People who watched the videos developed skills for identifying which posts contained a specific manipulation strategy. People who initially fared worst at spotting fake news in the pre-game quiz made the biggest improvements after playing the game.

The way forward

“Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” - Anthony Weldon, 1650

Occasionally as a fun way to communicate scientific information I take a meme and replicate it in real life. As the photo above shows, I did this with the ‘Change My Mind’ meme, which was a real stall that we set up in public locations in cities across the UK. The photograph went viral and encouraged some excellent conversations about vaccinations, nuclear energy, what constitutes truth and the impacts of misinformation, among other topics. Interestingly, I found that when they saw the image online people were more likely to dig their heels in due to their biases, but in person only a few people who approached us initially disagreed with the sentiment of the meme. In both cases, most people simply had questions and I and others were able to address those thanks to the attention-grabbing nature of the meme. In person, we found that the real-life-meme made people smile and engage with us and that the topic drew them into having open conversations with us about myriad topics.

People often ask how I stay calm when countering constant ad hominem attacks, gish-galloping and sometimes outright insults. As Mr Spock once said, “Reverting to name-calling suggests that you are defensive and, therefore, find my opinion valid.” My answer is that I don’t take people’s biases personally - after all, I used to believe misinformation myself. We have all done so at some point in our lives, and we are all susceptible to believing misinformation in the future. While it’s worth learning to identify the few people who hold fundamental beliefs on a topic that simply cannot be changed, to save wasting your time debating them, remember that for most people these messages do have an impact. It took me years to change my mind from being against nuclear energy to being in favour of it, and every person who took the time to dispel the misinformation I believed, and provide better sources for me to read to counter my viewpoints, had an impact on my beliefs.

Inoculation aside, one of the arguments made in Foolproof is that media literacy is an essential topic for schools to teach. It gets to the root of the problem, while inoculation theory deals with the symptoms. I have a theory that the reason Finland has the only Green Party in the world that is openly pro-nuclear, environmental groups that also support nuclear, and excellent climate policies, is thanks to the country’s education system, which includes media literacy and emphasises critical thinking.

Information literacy allows a person to find, understand, evaluate and use information effectively so that they can develop the ability to detect misleading news. Media literacy focuses on knowledge and skills for the reception and dissemination of information through the media. Ensuring that these topics are covered in education systems seems like a no-brainer - especially with younger generations who are growing up in a fully digital world.

I caught up with van der Linden to see what the reception to his book has been like since it was published. “I was particularly humbled and surprised by the end of year praise,” he tells me. Foolproof was named a Financial Times and Waterstones book of the year, a Nature Top 10 Book of 2023, a best behavioural science book, and won the British Psychological Society Book Prize 2023 (for popular science).

“I definitely didn't anticipate that and am very humbled by the reception. I am also happy to see the methods being put into action by social media companies, for example, Google did a new much larger YouTube campaign in Germany after the book was released prebunking common misinformation techniques reaching over 50% of the German population on social media. So it's good to see the approach being scaled. Ultimately I wrote the book to help people identify misinformation and manipulation so that's the most important feedback to me.”

There’s a vast amount of useful information in van der Linden’s book, but instead of trying to cover every concept here, I urge you to read it. It will, without a doubt, open your mind to many new ideas, and help you to navigate a misinformation-filled world. Mr Spock once said that “Evil does seek to maintain power by suppressing the truth”. I believe that humans need to get smarter at overcoming their biases and that this is an essential next step in our social evolution if we are to become a truly technologically advanced civilisation. None of us is entirely foolproof, but in the war against misinformation, it is surely something to aspire to achieve.

Thank you for this well reasoned and thoughtful article. Happy New Year and may your continuing efforts help educate the public on the importance of energy in their everyday lives. Best wishes, Dick Storm

My grandfather might have put it differently, but it took some grit to write this piece. The first comments to the post illustrate the problem being addressed. Critical thinking is a subjective skill. For me it means being calm enough to consider new information, to try to put myself in the other person’s position. Try to play debates out in your head, and argue as fiercely as you can against what you believe to be true. Try to understand why a conclusion diametrically opposite to yours could be believed, even if emotionally motivated. Then do a little research. Read the protagonist and antagonist data, review anything you believe to be objective. Then do simple math. A pencil, calculator, and an envelope can do wonders for understanding. Artificial intelligence will most likely be able to present very believable videos, articles, etc., which have been weaponized to divide civil society more. Cooler heads must prevail.