Is this the ultimate solution to permanently storing long-lived nuclear waste?

Renewed interest in deep geological repositories is reviving an old debate

Deep geological repositories (DGRs) are underground facilities constructed at depths ranging from around 200 to 1,000 meters to securely store different types of hazardous and radioactive waste. These repositories use multiple protective barriers to prevent the release of radioactivity, ensuring the material can be stored safely for an indefinite amount of time. While this may seem like an ideal solution, DGRs remain controversial, facing opposition from anti-nuclear groups as well as scepticism within parts of the nuclear advocacy community.

Are they necessary? Some nuclear advocates argue that DGRs are excessive, suggesting they reinforce the idea that nuclear waste is inherently dangerous, which only strengthens existing fears about spent fuel. On the other hand, many experts within the scientific community believe that long-lived high-level radioactive waste demands a secure storage solution capable of safeguarding the material for thousands of years. Both sides make valid points.

Nuclear waste that can’t immediately be disposed of is usually temporarily stored in robust casks on nuclear power plant sites. While these casks effectively shield against radiation and are built to last, there is a growing consensus that a permanent, secure storage solution is needed once the casks can no longer serve their purpose. This is where deep geological repositories come in - offering a secure site to bury the waste at depths similar to those from which it was originally mined, ensuring its isolation for millennia without the risk of disturbance.

I understand why some nuclear advocates are concerned that discussing long-lived nuclear waste in this way might make the issue seem greater than it is. However, I also believe we need to be cautious about letting anti-nuclear activists shape decision-making to the point where we avoid discussing critical issues like permanent long-term storage. Many other industries store waste underground without controversy. As is often the case, it’s not the dramatic problem anti-nuclear groups make it out to be.

After years of discussing spent fuel from a different perspective, I’ve found that most people are open to understanding the complexities of waste management. My takeaway is that it’s crucial to focus on discussing permanent waste storage rather than avoiding the topic and allowing anti-nuclear activists to shape the narrative. When I talk to people about deep geological repositories and point out that hazardous waste from other industries, including mercury, cyanide, and arsenic, is already stored safely in these underground sites, it often helps alleviate people’s concerns. For example, the Giant Mine in Canada, which, once a gold mine, now stores arsenic trioxide dust - a substance so lethal that even tiny amounts can be deadly. If you research it, you'll see why burying such material far below ground, as far away from animal life as possible, is the safest option, rather than leaving it exposed above the surface.

For my full breakdown of nuclear waste, read:

This isn’t to say that storage casks can’t be used for decades, but they are not a permanent solution. The scientific consensus is that we need to build repositories as a long-term permanent solution for nuclear waste. These repositories are designed to provide a high level of isolation and containment without requiring continuous future maintenance. This shouldn’t be a controversial stance, so let’s normalise it rather than allowing anti-nuclear activists to dominate the conversation.

In my view, we need to plan much further ahead for permanent waste management than we currently do. Most people would agree that future planning is essential, but how far is enough? Many challenges require long-term foresight, yet few receive the attention they deserve. As I’ve mentioned before, this theme is central in the works of science fiction author Isaac Asimov, who imagines civilisations stretching hundreds of thousands of years into the future, attempting to anticipate their needs for the good of humankind.

From East to West, we are often plagued by short-term thinking. Politicians rarely look beyond their short term in office, which usually only spans a few years. At most, world leaders might consider the future a few decades ahead. But what about hundreds of years ahead? One of the most influential nuclear advocates I know takes this long-term view - Michael Shellenberger.

Many people don’t know it now, but America’s shift from anti-nuclear to pro-nuclear can largely be attributed to him. When I worked with Mike years ago, I asked him how he managed to endure so many years of criticism, especially while working mostly alone, balancing advocacy, securing funding, and managing a team. The change in nuclear policy in the US didn’t happen by chance. While there are many active players in the field now that nuclear has gained popularity, Mike carries the scars from doing the vital groundwork when supporting nuclear was one of the most controversial positions you could take. I once asked him what kept him going through those tough times, and he told me he was driven by the idea of contributing to something with a lasting legacy - a nuclear reactor that would continue to benefit humanity long after his lifespan. This reminds me of a line from the play Hamilton: "I want to build something that’s going to outlive me." It seems that, regardless of political beliefs, this is a common feeling among pioneers, but such individuals are rare, and it’s difficult to remain focused on long-term goals amid the constant noise of current affairs.

Nuclear energy is a rare example of where forward-thinking is integral to the success of the technology. It’s the ultimate test for the pioneer, requiring a perspective that extends far beyond one’s lifetime, which is difficult to do but necessary for humanity to thrive.

Read my post on Asimov’s writings:

As countries increasingly turn their attention to nuclear energy to meet growing energy demands and ensure energy stability, more are now exploring or planning their own deep geological repository projects. In the past, many such projects failed, such as The Yucca Mountain project in Nevada. The site was once proposed as a repository for nuclear waste but has faced significant opposition and legal challenges, preventing it from moving forward. Although the project was approved by the 107th US Congress in 2002, it was met with widespread public resistance and fierce political opposition. The failure to build the repository was found to have been due to political, not technical, or safety reasons. As a result of decades of anti-nuclear campaigning, the US does not have an operational deep geological repository and lags behind with plans to build one.

Japan has faced similar problems. Its Atomic Energy Commission and other governmental bodies have been evaluating potential sites for a repository for years, but the process has been slow, held up by various challenges, including geological assessments, regulatory hurdles, and public opposition to the idea of building a deep geological repository in the country. In the past, Japan had considered the Mutsu Bay area in the northern part of the country as a potential site for a repository, but these efforts have been met with significant local resistance.

However, some countries have had the foresight to build DGRs, and they’re ahead of the curve in this respect. Let’s take a look at who they are.

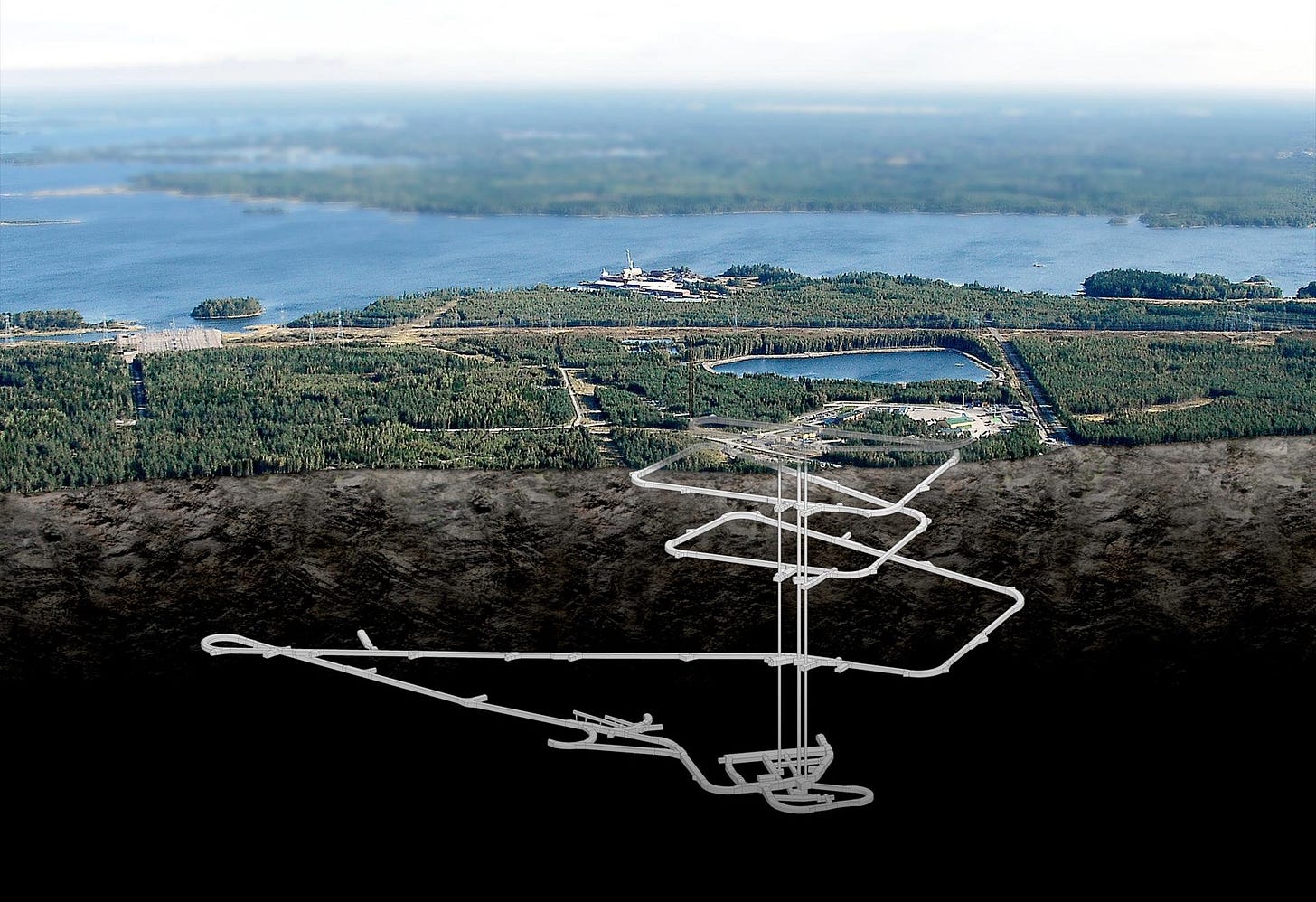

Finland has already constructed the world's first long-term repository for radioactive waste: Onkalo, which translates to ‘pit’ or ‘cavity’ in Finnish, is located 450 meters underground. Onkalo is essentially a vast network of tunnels designed to isolate spent nuclear fuel. The facility features robotic vehicles to transport the waste and a ventilation system to maintain air quality. I spoke with a Finnish MP who told me that Finland could, in the future, allow other countries to store their waste in their repository - for a price. Thinking ahead. Smart.

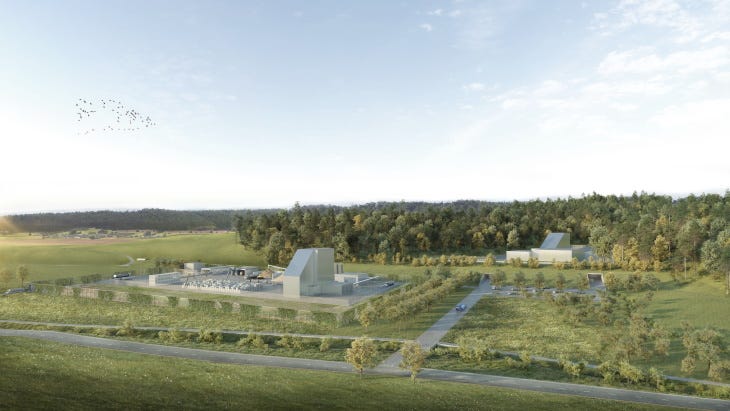

Sweden is following in Finland’s footsteps and is in the process of constructing the world’s second deep geological repository for nuclear waste, the Forsmark Deep Geological Repository. The site is located near the Forsmark nuclear power plant, and the project is expected to be operational sometime in the 2030s.

Switzerland has been phasing out nuclear power since 2011, but the country is still planning its own deep geological repository, with a site chosen in Nördlich Lägern. This facility will be a combined repository that is suitable for all types of radioactive waste. The site’s approval is not expected until 2030 and will be subject to an optional referendum. Once approved, it will take another 30 years or so before waste emplacement operations can begin. While this may seem like a slow and cumbersome process, it’s notable that it’s taking place alongside the (temporary?) phase-out of nuclear energy. This highlights a balance between short-term political decisions aimed at satisfying voters, and long-term, practical thinking that indicate that science and ambition are still guiding the country’s approach on some level.

France, the bastion of nuclear success, is working on a deep geological repository project called Cigéo, an acronym for “Centre Industriel de Stockage Géologique" or "Industrial Centre for Geological Disposal". Cigéo is still in the planning and regulatory stages, with construction expected to begin soon. The principle of geological disposal was put into French law in 2006, but anti-nuclear activists have slowed down the process with constant protests and fearmongering. The decision rests with the Nuclear Safety Authority, which has until 2027 to decide whether or not to authorise the construction of the site.

Canada: Fourteen years after starting its consent-based siting process, Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation and the Township of Ignace have been selected as the host communities for Canada's proposed deep geological repository. Again, the process has been slow, but it’s a solid approach to secure approval at the outset and work collaboratively with communities rather than facing insurmountable opposition later. When the consent-based site selection process was launched in 2010 with the caveat of only considering "informed and willing" hosts, 22 communities came forward to express an interest in learning about the project and exploring their potential to host. The two sites that were chosen are still in the early stages, with environmental assessments and public consultations currently underway.

Storing nuclear waste in casks for decades is fine, and we certainly shouldn’t bury it while it can still be recycled, as that would be wasteful. However, once the spent fuel has been fully used, it should be returned from whence it came - deep underground. This means openly discussing permanent waste storage rather than avoiding it - after all, many industries manage waste produce and bury waste in DGRs without sparking controversy - and looking far beyond our own lifetimes. Asimov would be proud.

I like James Lovelock's take on nuclear waste storage:

"Wild plants and animals do not perceive radiation as dangerous, and any slight reduction it may cause in their lifespans is far less a hazard than is the presence of people and their pets. It is easy to forget that now we are so numerous, almost anything extra we do in the way of farming, forestry and home building is harmful to wildlife and to Gaia. The preference of wildlife for nuclear-waste sites suggests that the best sites for its disposal are the tropical forests and other habitats in need of a reliable guardian against their destruction by hungry farmers and developers."

The Google AI says, "Falls are the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths worldwide, killing an estimated 684,000 people each year." It also says, "The Chernobyl accident in 1986 resulted in 28 direct deaths, 19 deaths not entirely related to the accident, and 15 children who died from thyroid cancer," and "The Fukushima Daiichi accident in 2011 resulted in no casualties," and "The Windscale fire in 1957 resulted in over 100 fatalities." So if you believe Google, FALLS kill over 4000 times more people every year than all the reactor accidents in history. The LNT model governing radiation safety policies and the ALARA policy crippling the nuclear power industry are based on the premise that even one death due to radiation from a reactor accident would be more horrible than the 8 million deaths a year from fossil fuel pollution alone. Whaaaat??

If you walk down concrete steps without a railing, even if you wear a crash helmet, I can state confidently that you are insanely inconsistent if you worry about leaks from stored fuel rods from reactors. Same if you ever get behind the wheel of a car, or go swimming, or use medicine of any kind, or eat or drink anything unsterile, or... basically, live in the world.

How did the Auntie Nukes manage to create this insanity? Can't people do arithmetic? Can't people even tell the difference between a LITTLE and a LOT?

I hate to tell you, folks, but none of us is getting out of this alive. Your probability of dying is 1. You have a limited opportunity to influence what you die OF, and WHEN; but in the meantime you might want to think about how you want to spend the rest of your life.